Army children's birthplaces can speak volumes about their families' peripatetic lifestyles, as well as the times in which they grew up. Looking at a page of the 1891 national census for England and Wales listing families living in the 20th Hussars' cavalry barracks in Aldershot, for example, reveals that the daughters of one family, respectively aged three and two, were born in Cairo, Egypt, and Norwich, England, places to which their sergeant father had been deployed, accompanied by their 'on-the-strength' mother. The birthplaces of army children born between the wars, if not in India and other sunny stations, are likely to be those camps and garrisons where the British Army retained permanent bases (and still do), such as Catterick, Aldershot, Colchester, Tidworth and Bulford. Following World War II, locations further afield joined the list of likely places of birth, including Malta, Cyprus, West Germany and Northern Ireland.

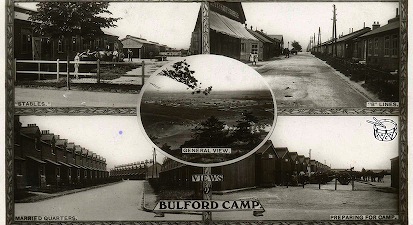

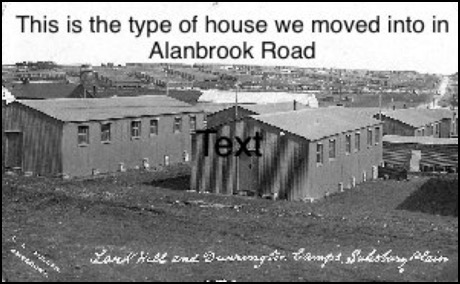

Various aspects of Bulford Camp pictured in a postcard dating from the World War I era.

Various aspects of Bulford Camp pictured in a postcard dating from the World War I era.If the civilian aspects of life outside barracks, camps and garrisons (such as the climate, the language or dialect spoken and the currency used) can change with bewildering frequency (often within a matter of months, but more usually within the space of a year or two) the touchstones of army children's immediate environment 'within the wire' typically remain reassuringly constant. Over the centuries, the ways in which the British Army has catered for the families of its serving soldiers have gradually expanded from being limited to providing accommodation and schooling to supplying spiritual, community, practical and personal support and advice, courtesy of the chaplains, what is today known as the Army Welfare Service (AWS) and affiliated charitable bodies like the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Families Association (SSAFA) Forces Help. And when abroad, the challenge of living in an alien culture may additionally be cushioned by, for instance, the availability of certain familiar British products and foods stocked by the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI); medical and dental treatment and care; and, thanks to the British Forces Broadcasting Service (BFBS), British television and radio programmes.

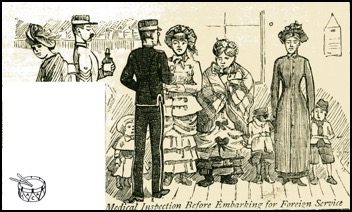

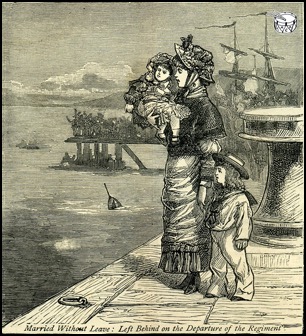

PICTURES: THE CONTRASTING FORTUNES OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY FAMILIES PRIOR TO OVERSEAS POSTINGS ("TOMMY ATKINS" MARRIED – PAST AND PRESENT, 1884)

The two images below illustrate the contrasting fortunes of those nineteenth-century army families that, on the one hand, were accorded 'on-the-strength' status and were therefore allowed to accompany their soldier husbands and fathers on overseas postings, and, on the other, were not recognised as being in any way the army's responsibility and were consequently left behind to fend for themselves. While the first image shows a line-up of army wives and children presenting themselves for a medical inspection (and, by the look of it, a dose of some sort of 'tonic') before setting sail – probably for India – the second depicts a wife whose marriage had taken place without the army's permission standing bereft with her two children on the quayside as the troopship carrying her husband and their father sails away. Both of these scenes are taken from "Tommy Atkins" Married – Past and Present, a composite print that was first published in The Graphic on 12 January 1884 (click here to see it).

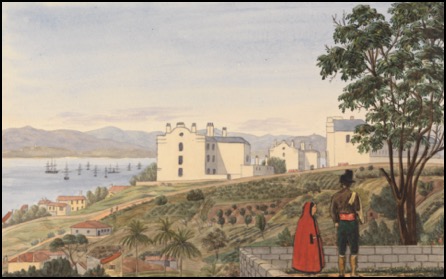

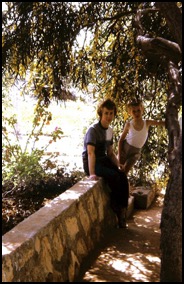

PICTURES: SOUTH BARRACKS, GIBRALTAR

The old colour postcard below presents a view of Gibraltar’s South Barracks, which date from the 1730s.

The South Barracks, Gibraltar (1844), below, is the work of George Lothian Hall (1825–88). Created using watercolour, pen and black ink and graphite on thick, moderately textured, cream wove paper, it is now part of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Written on a fragment of the original mount is the following inscription: ‘The South Barracks Gibraltar – part of the Bay – and/ the mountains of Andalusia/ from the Naval Hospital/ March 1844.’.

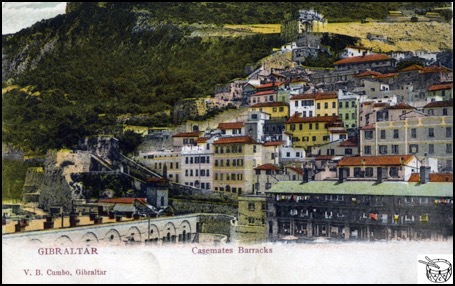

PICTURES: CASEMATES BARRACKS, GIBRALTAR

The colourful old postcard seen below presents a view of Casemates Barracks, in Gibraltar, which dates from 1817. No longer a barracks, the buildings and surrounding area have been redeveloped (click here for more from Gibraltar’s tourist board.)

The illustration below is part of the Yale Center for British Art’s Paul Mellon Collection. Created by George Lothian Hall, it shows the officers’ quarters and Casemates Barracks in 1843.

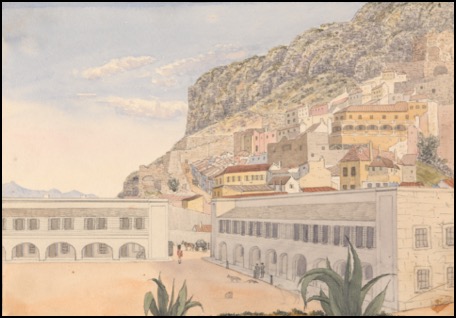

PICTURE: THE BARRACKS, UP PARK CAMP, KINGSTON, JAMAICA

The photograph below is part of an album of views of Jamaica. Reproduced courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library, it shows a view of the barracks at Up Park Camp, Kingston, Jamaica. British soldiers were stationed at the camp following its establishment in 1784 until 1962, and it was home to many of their families, too.

Picture: The New York Public Library Digital Collections: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-fb23-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Click here for further information about Up Park Camp on the Jamaica Defence Force website.

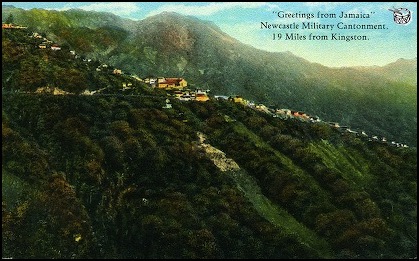

PICTURE: NEWCASTLE MILITARY CANTONMENT, JAMAICA

A picture-postcard view (below) of 'Newcastle Military Cantonment', Jamaica, once home to generations of army children. Newcastle Barracks was established on the instigation of Major General William Gomm in Jamaica's Blue Mountains in 1841, mainly because, at around 1,128 metres (3,700 feet) above sea level, its hillside location was considered healthier than that of Kingston, where the British were prone to succumbing to yellow fever.

In her autobiography, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands (1857), Mary Seacole (1805-81), née Mary Jane Grant, the Kingston-born nurse and healer, wrote that by 1843, she had 'gained a reputation as a skilful nurse and doctress, and my house was always full of invalid officers and their wives from Newcastle, or the adjacent Up-Park Camp.' A decade later, Mary's services were in even greater demand, 'for the yellow fever never made a more determined effort to exterminate the English in Jamaica than it did in that dreadful year. . . . My house was full of sufferers - officers, their wives and children. . . . It was a terrible thing to see young people in the youth and bloom of life suddenly stricken down, not in battle with an enemy that threatened their country, but in vain contest with a climate that refused to adopt them. Indeed, the mother country pays a dear price for the possession of her colonies.'

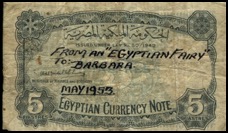

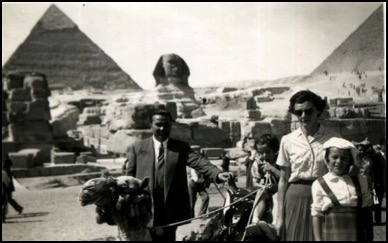

PICTURES FROM THE READ FAMILY ALBUM OF ABBASSIA, CAIRO, EGYPT, 1920S, AND A REQUEST FOR INFORMATION

Simon Burgess has generously contributed to TACA photographs from his great-grandparents' family album. Simon writes:

'My grandmother, Eileen Barbara Read, was born on 15 January 1928 at the Married Families' Hospital, Abbassia, in Cairo, Egypt. Her birth certificate was registered on 30th January 1928 by Major W B Hayley, Commanding Officer, K Battery, Royal Horse Artillery (RHA).

Her mother (my great-grandmother, Daisy Marion Read, née Preston) was a nanny, and at the time of her marriage, on 4 July 1927, was registered as living in the 'Ordinance Depot, Abbassia' (according to the wedding certificate). Eileen's father (my great-grandfather, Richard George Read, who was a lance sergeant in 'K' Battery, RHA, at the time) was stationed in Egypt between 1922 and 1930. Some of the photos in their archive are reproduced below, illustrating the life that they led during this period.

I understand that Daisy may be in a photo that TACA has of the school in Abbassia from this period [see 'PICTURE: THE GARRISON SCHOOL, ABBASSIA, CAIRO, EGYPT, IN 1928'].

Though I have lots of information about my great-grandfather's career, I have very little about Daisy and her time in Egypt. If anyone has any information about the school in Abbassia, about British nannies in Egypt during this period, or about Daisy herself, I'd be most grateful.'

If you have any information that may help Simon learn more, you can e-mail him at sighburge@yahoo.co.uk.

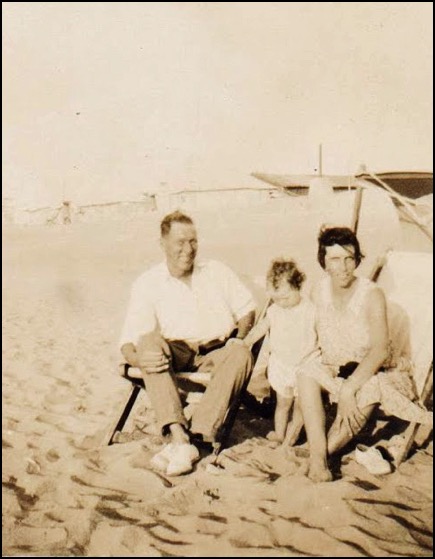

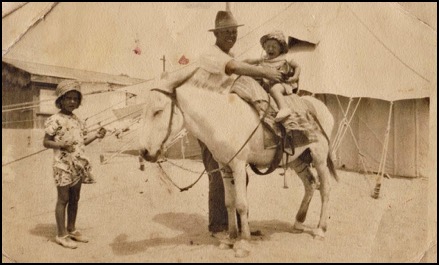

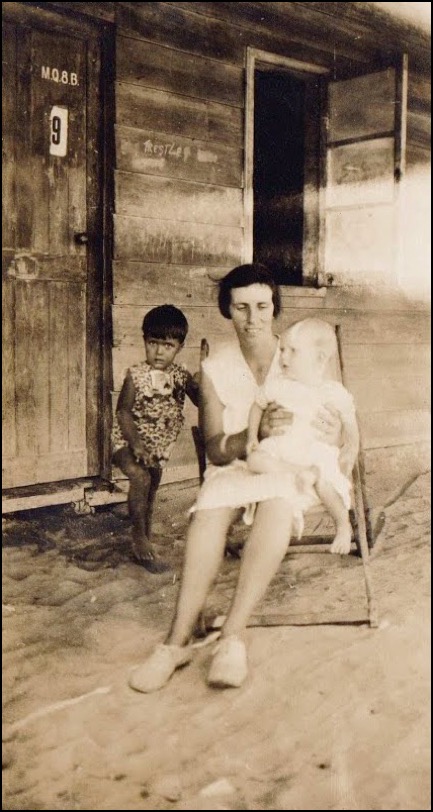

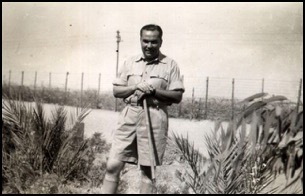

Below: Lance Sergeant R G Read, of 'K' Battery, RHA, Eileen Read, and Daisy Read, taken about 1928/9, Sidi Bishr Married Families' Camp, Alexandria, Egypt.

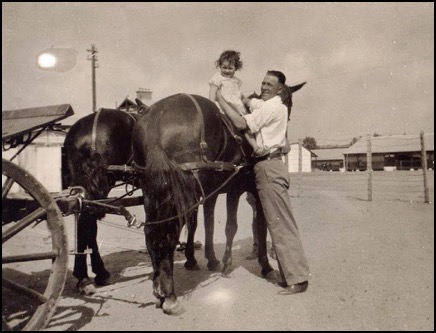

Below: Lance Sergeant R G Read and Eileen Read, about 1929.

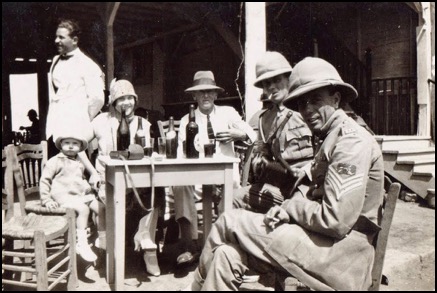

Below: Eileen Read (about 18 months old here) seated, others sadly unknown, taken about 1928/9 at the NCO's mess.

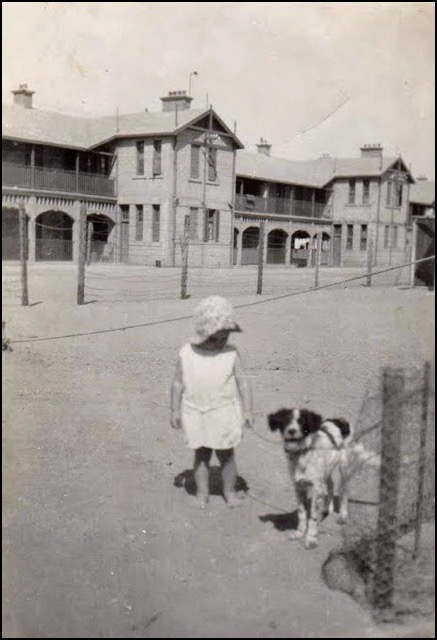

Below: Eileen Read with dog, Port Said or Sidi Bishr Married Families' Camp, taken about 1928/9.

Below: Lance Sergeant R G Read, with Eileen Read (seated), other girl sadly unknown, taken about 1928/9.

Below: Military Families' Camp, Sidi Bishr, taken about 1928/9.

Below: Daisy Read and Eileen Read, Sidi Bishr Married Families' Camp, 1928/9.

Below: Daisy Read, Eileen Read, and friend, Sidi Bishr Married Families' Camp, taken about 1928/9.

Below: Eileen Read and friend, Port Said (my favourite photograph of my gran in the collection!)

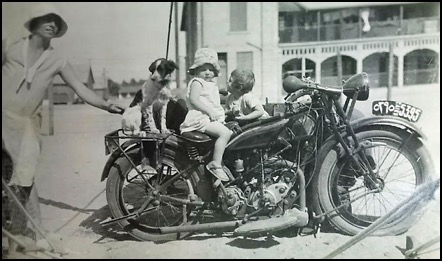

Below: Lance Sergeant R G Read and Eileen Read on his Rudge Whitworth 500cc, most likely outside Port Said.

Below: Daisy Read and Eileen Read (seated) on R G Read's, Rudge Whitworth 500cc, most likely Port Said.

PERSONAL STORY: 'IT WAS A MAGICAL PLACE, WITH PALM TREES AND COFFEE PLANTATIONS', JAMAICA, 1928–30

With her father serving with the 2nd Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, Mairi Paterson's army childhood began and ended in Stirling, Scotland, where she lived from 1921 to 1922, and again from 1934 to 1938. The years in between saw her family posted to Aldershot, Hampshire, between 1922 and 1924; the Isle of Wight (1924–28); Jamaica (1928–30); Wei-Hai-Wei (today called Weihai), north-eastern China (1930–32, and click here for Mairi's memories of travelling there in 1930, and see below for her description of living in Wei-Hai-Wei); and Hong Kong (1932–34, see below); click here to read of her journey back to Scotland: ‘PERSONAL STORY: SAILING FROM HONG KONG HOME TO SCOTLAND, 1934’; and see below to read of her time living at Stirling Castle: ‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘NOW I WAS LIVING IN A CASTLE: STIRLING CASTLE’, 1934’). In the account that follows, Mairi outlines the early years of her life as an army child, before recalling in evocative detail the two years that she and her family spent in Jamaica.

'My father, Hugh Campbell, from Lochgilphead, Argyll, joined the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders at Fort George. He became an instructor and was a good shot, competing at Bisley [Surrey]. When World War I broke out, he was seconded to the King's West African Rifles in Nigeria as an instructor. He was wounded in what was then German East Africa. He returned to the Argylls and was stationed at the depot, Stirling Castle, when I was born. We moved to Aldershot, and then to the Isle of Wight, where I started school.

The 2nd Battalion was then assigned a "tour of overseas duty" and was posted to Jamaica. My mother, brother and I did not travel then, as my grandfather was ill, but followed in May 1928, travelling from Liverpool in the SS Orduna. The camp was just outside Kingston, and during the hot season, it was almost too much to bear. Every so often, we were sent up to Newcastle, a hill station in the Blue Mountains. The steep road, with its hairpin bends, ended in the square formed by the church, the school, the orderly room and the NAAFI. There were steep paths up to the bungalows, and we had a donkey to help us get up and down them. When we went to the shop, my mother led the donkey, I sat on its back, my little brother (aged three) was in one pannier and the other was for the shopping. It was a magical place, with palm trees and coffee plantations. There were hummingbirds and mongooses, and it was so steep that one looked down on the roof of the house below. We would catch some fireflies, put them in a glass jar and eat our evening meal on the verandah by their light; then we would release them into the warm night again. On one visit, we were struck by a hurricane. Sent home from school early, I helped put the shutters up on the windows, take in everything possible, tie down everything else – and then watched as my party dress was whipped off the line and disappeared!

Kingston was very different. Our house was in quite a large garden, with four banana trees, a mango tree, a calabash tree and masses of plants. There were beautiful blue and green lizards and many birds. But there were also the terrifying large land crabs, which came out in the dusk, as well as scorpions, which were liable to hide in your slippers. I once watched as a piece of bread that I had put down moved swiftly over the floor, carried away by the ants. The legs of all our pieces of furniture stood in tins of paraffin. At night, you had to get under the mosquito net as quickly as possible and let in as few of the pests as you could.

I attended the army school nearby, and achieved the distinction of being expelled at the age of eight. The teacher must have forgotten that the troops there were not only Scots, but Highland. She gave us a lesson about the Jacobite rising of 1745 and described the clans as ignorant, illiterate savages who rebelled against their rightful king and, fortunately, were defeated by his brilliant son, the Duke of Cumberland, at Culloden [in 1746]. I was an early reader and had just finished D K Broster's trilogy about the '45, so stood up in a fury and said that she was a liar: the clans had an old culture, and Cumberland was remembered as "Butcher" Cumberland for his cruelty. I was immediately sent home. Two days later, my father was told that the school would overlook my behaviour and allow me back. I refused to go, saying that I would never learn anything from someone so stupid. It was eventually settled by a visit from the colonel. He was MacLaine of Lochbuie, a clan chief. He agreed with me, but said that I had also to learn things like arithmetic, and that I would have a different teacher. When I think of it now, I am amazed at everyone's patience. But I went back.

One great worry was becoming ill. Dengue fever was very prevalent. However, we had a "quinine cup": this was roughly made from a piece of a branch of the cinchona tree, and water put in it turned to quinine. The doses were: ten minutes for my brother, twenty for me and thirty for my parents. (I still have it, though it takes much longer now.) As a result of a bad outbreak, nurses from Kingston came to help, and we met a family, also called Campbell, whose members had been among the early settlers in Jamaica. Many years later, I met a black medical student, also a Campbell, who told me that his great-grandfather had been a slave on that plantation, and that on gaining his freedom, he had taken the name as his surname.

After two years in Jamaica, the battalion got its next posting – to northern China. We were to go through the Panama Canal and over the Pacific on a troopship!'

Mairi Paterson (née Campbell, b.1921).

PERSONAL STORY: 'I AM GLAD THAT I CAN REMEMBER WEIHAI AS IT WAS EIGHTY YEARS AGO'

In the previous instalments of her account of growing up as an army child between 1921 and 1938, Mairi Paterson described living in Jamaica (see above) and then sailing in a troopship with the troops and families of the 2nd Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (see 'PERSONAL STORY: CROSSING THE PACIFIC, 1930'), from Jamaica to Wei-Hai-Wei (today called Weihai), in north-eastern China, to which her father had been posted, and where her family would consequently live from 1930 to 1932 before moving on to Hong Kong (see 'PERSONAL STORY: GOING TO SCHOOL BY RICKSHAW AND KEEPING A LOW PROFILE IN HONG KONG, 1932–34', below) and then returning to Scotland (click here to read about the journey: ‘PERSONAL STORY: SAILING FROM HONG KONG HOME TO SCOTLAND, 1934’, and see below for her time living at Stirling Castle: ‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘NOW I WAS LIVING IN A CASTLE: STIRLING CASTLE’, 1934’). This part of Mairi's story has special historical significance because, as she notes, 'At that time Wei-Hai-Wei was leased to the British as a resource for the British navy, and I feel I may be one of the last [British] people who can remember life there and its return to the Chinese in 1932 as my brother and myself were the only British children there'. Read on for more.

'The men of the community were fishermen, and their junks and sampans crowded the harbour. The rising slope behind was cultivated by the women, the main crop being peanuts, as well as crops for food. The district commissioner, Reginald Fleming Johnston, lived in the big house on the point. He had been tutor to the young emperor, who had been overthrown by the communists, and he was an admirer of the imperial Chinese way of life. He had become a Buddhist and lived as a mandarin in Chinese style. He was Scottish and was, perhaps, more welcoming to us because of this. (In the film The Last Emperor, he was played by Peter O'Toole.)

We now had to settle into our new home. It was across the road from the parade ground, and was quite roomy. The most noticeable feature was a wide, enclosed verandah, with a bench that ran along it, under the windows. It soon became our playroom. At the back of the house, the kitchen and bathroom had flagged-stone floors, with drains that led out to the courtyard outside, which was surrounded by walls and had a large, heavy gate. My mother had a very special pair of very handsome curtains, and as soon as they were up, we knew that we were at home. Sometimes they were full length, sometimes folded in half, and sometimes over a door instead of a window – but they were always there.

The weather became colder and colder, and I acquired a fur coat and a fur hat with earflaps. My little brother, Euan, had a furry jacket that made him look like a teddy bear. We were the only European children there, though later Sergeant Sinclair's wife joined us with their newly born baby daughter. My mother asked an uncle to send out books. A huge box arrived with the collected works of Sir Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, John Buchan and, surprisingly, Zane Grey. Best of all was Andrew Lang's History of Scotland, which became my favourite book. My mother was the strictest teacher I ever had. Every morning, I read a chapter of the Bible and learned some of the Shorter Catechism. Then I studied English and arithmetic, with history and geography in the afternoon. During the week, I read a book, and on Saturday morning, wrote a summary of the plot and chose two characters and two incidents and explained why I'd done so.

We made friends easily, and local children came to play on our verandah. My best friend was Soong Mei-ling. We could not speak much to each other, but did everything together. On Saturday evenings, my mother held open house for any of the men who cared to come. She made oatcakes, scones and shortbread, and they played games like I-spy with us. Sunday evenings meant a visit to Mr and Mrs Hill, kindly elderly missionaries, where we sang hymns around the piano and ate parkins. There were usually about ten of us there, and we all walked home through the cold, clear night.

There was plenty of entertainment as each platoon organised a concert or whist drive each month. Euan and I always had the best seats, and were ready to enjoy what we knew would be coming, depending on which platoon was host. Sergeant Grant would sing a selection of Harry Lauder songs; Second Lieutenant Graham would deliver a humorous monologue; my father would sing "The Road to the Isles"; and so on. We were delighted to hear our favourites again.

THE PASSING OF THE SEASONS IN CHINA

Then it was Christmas. I had begun to have serious doubts about Santa Claus, but said nothing to Euan. On Christmas morning, my father reported that Santa had not been, but just as Euan began to cry, there was a loud knock on the verandah door. My father went to answer it and we heard, "Hello, Santa, you’ve made it". We could see faintly through my bedroom curtains, and watched my father come up the verandah, followed by a figure with a sack over his shoulder. "Have they been behaving themselves?" asked Santa. He did not sound very "Ho, ho, ho!" but instead rather grumpy. There was a long pause before my father replied, "On the whole, they’ve been quite good". Then Santa said, "Well, they were quick to write to tell me what they wanted, but they didn’t bother to say where they were. Last time I came, they were in Jamaica. How was I supposed to know they were in northern China?" We shouted, "Sorry, Santa, we forgot". My father persuaded him that he needed something to warm him up, and a little later Santa sounded more friendly as he said, "I’m running very late and I've still got Siberia to do. Remember to let me know next year". It was much later that I realised that my presents were very Chinese in type!

At the Chinese New Year, we watched the dragon weave and dance his way among the trees and enjoyed the fireworks. But the most memorable moment came one evening, when we went down to the harbour. Most of the village had gathered there, and many were holding little wooden boats, each of which had a small candle fixed in it. As the tide went out and one of our pipers played a lament, the little boats, each in memory of one of the villagers lost at sea, were launched. We watched as the glimmering lights disappeared into the darkness of the China Sea.

Summer came, and Wei-Hai-Wei was transformed. The shuttered house was opened up and cleaned and revealed to be an hotel for the Royal Navy wives and families. The ships arrived – battleships, destroyers, submarines – and the harbour was crammed. Suddenly, there was a busy social life, both on the island and on the mainland. A magician came, and Euan and I were asked up on the stage to help with his conjuring tricks. Dances were held, and the portly Major Hyde taught me to waltz, telling me that I would not get dizzy if I kept my eyes on his middle button. Best of all, a performing-dogs theatre came. My father was very helpful with their accommodation and exercise area, and when one of the cast gave birth to a litter of pups, I was given one. We called him Bodach (Gaelic for "old man") because of his grey whiskers. He was a very intelligent and tough little Pekingese who would tackle anything. (No wonder the Chinese call them "lion dogs".) Instead of staging whist drives and concerts, we now hired sampans and sailed a few miles to a beautiful sandy bay, where we dived and swam from the boat and had picnics on the shore. A greasy pole was run out over the bow, and the men would have pillow fights on it till both combatants fell in.

However, this simple, but happy, life was to end. Its lease to Britain had ended on 1 October 1930, but Wei-Hai-Wei then became a special administrative region until 1932, when it was finally handed back to China. The formal ceremony was very impressive, with the troops standing stiffly to attention, bugles and pipes, speeches and, most notably, the commissioner, Fleming Johnston, formally dressed and wearing a top hat!

We were now to join the rest of the battalion in Hong Kong – a busy city – and I would be back in an army school. Neither prospect attracted me. We had grown to feel part of the life of the place, rather than standing outside it, and had made many friends.

"I AM GLAD THAT I CAN REMEMBER IT AS IT WAS EIGHTY YEARS AGO"

I believe that Weihai is now a busy industrial town, and photographs of it show factories and high-rise flats. It has train and bus connections to the rest of China, as well as a busy harbour, with cargo ships and trade with South Korea. I am glad that I can remember it as it was eighty years ago.'

Mairi Paterson (née Campbell, b.1921).

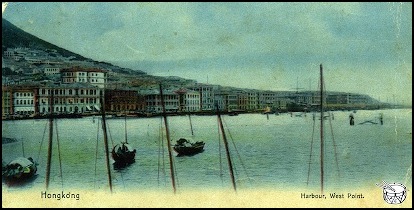

PERSONAL STORY: GOING TO SCHOOL BY RICKSHAW AND KEEPING A LOW PROFILE IN HONG KONG, 1932–34

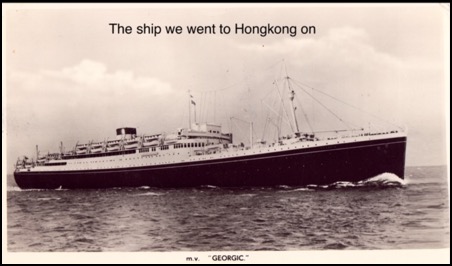

As a small girl, Mairi Paterson lived in Stirling, Aldershot and the Isle of Wight. Her soldier father's next posting then took her and her family, along with the 2nd Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, to Jamaica (see 'PERSONAL STORY: 'IT WAS A MAGICAL PLACE, WITH PALM TREES AND COFFEE PLANTATIONS', JAMAICA, 1928–30', above). A Pacific crossing in the City of Marseilles, an overcrowded troopship ('PERSONAL STORY: CROSSING THE PACIFIC, 1930'), having transported Mairi from Jamaica to Wei-Hai-Wei (today called Weihai) two years later, she lived in this north-eastern Chinese seaport until 1932, one of only two British children there ('PERSONAL STORY: 'I AM GLAD THAT I CAN REMEMBER WEIHAI AS IT WAS EIGHTY YEARS AGO'', above). In this, the next instalment of her story, Mairi tells of the two years (1932–34) that she and her family subsequently spent in Hong Kong, at a time when the Japanese threat to it was becoming increasingly pronounced. (Click here to read of her next journey: ‘PERSONAL STORY: SAILING FROM HONG KONG HOME TO SCOTLAND, 1934’, and see below for her time living at Stirling Castle: ‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘NOW I WAS LIVING IN A CASTLE: STIRLING CASTLE’, 1934’.)

'Leaving Wei-Hai-Wei meant not only leaving the simple, friendly life of a small village for the noise and bustle of a city, but also rejoining the rest of the battalion. The families were housed in a four-storey block of flats, the President Apartments, in the heart of Kowloon, on a busy street. The camp was at Sham Shui Po, later to become notorious when it became an internment camp after the Japanese invasion.

My father became RSM [regimental sergeant major] of the battalion and spent most of his time at the camp, coming home only in the evenings. Our flat was on the top storey and on the corner of the building, so we had a very large verandah, running around two sides. It eventually became the home of our increasing number of pets, which included a parrot, two budgies, five goldfish, and a hen and a duck. The last two had been given as presents at New Year – alive, to be killed and eaten when required. After a couple of days, they had become pets, and we could not have eaten them! In addition, there were temporary residents: as I spent my pocket money buying the tiny wild birds that had been caged and were sometimes taken out by their owners, they spent a few days with us until we could go to the New Territories and set them free there. The flat roof of the block was a playground, particularly for flying kites on. Now there were neighbours all around us, and plenty of company.

We attended the army school on Gun Club Hill. It was some distance away, and every morning our rickshaws were waiting to take the children there. They were waiting, too, to take us home after school. I think the rickshaw men enjoyed this: after all, it was steady work, they got to know us, and there was always a lot of laughing and joking. Sometimes there were races on the way home. On one occasion, our rickshaw collided with another, went over and I was on the ground with my brother on top of me. I was quite badly bruised and scraped, and well remember the anti-tetanus jabs.

The school was next door to a Gurkha barracks, and the men smiled and waved when we were out in the playground. We were now back to formal lessons, with several teachers. One I remember fondly was Mrs MacMenamin. She was Irish, and had a lovely speaking voice. On Friday afternoons, the senior girls had sewing, and while we worked, she read us poetry – poems like "Cargoes", "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" and "The Traveller".

A cousin of my mother's, Hamish Cameron, was the managing director of a company engaged in the building trade, and he and his wife, Chrissie, and their two children lived in the area near the waterfront. They were very friendly and welcoming, and we spent a lot of time with them. They had a busy social life, and as there were many Scottish expatriates and a flourishing St Andrew's Society, we enjoyed many activities. I remember the trips to the sandy beaches on the island. On one occasion, I encountered a large jellyfish. I was delirious for two days, with a severe sting on my shoulder and an interesting spiral of red and swollen flesh down my arm as one of its tentacles had wound its way down it. It is very sad now to remember that the Cameron family suffered badly when the Japanese took Hong Kong, and that Chrissie died in Sham Shui Po Camp.

While we were there, an outbreak of diphtheria struck Kowloon. I went down with it, and, on Christmas Eve, was strapped securely onto a stretcher and taken by ambulance to the Star Ferry and across to Victoria Island. The hospital was high up on the Peak, and access was by a funicular railway. The stretcher was placed on the gap between the seats and attached to their supports. As we went up, I could see the streets, houses and shops receding from me. At one point, the climb was so steep that my stretcher and I were almost vertical. I must have been more ill than I realised because my father was told to be "ready for the worst". However, I recovered and quite enjoyed the lazy days of my convalescence.

Quite soon I got to know the Star ferries well. I moved on to secondary school and travelled daily to the Central British School on the island. I enjoyed it very much, especially as several friends from Gun Club Hill were also there.

"THEIR BODIES, FIXED ON POLES, WERE BEING PARADED THROUGH THE STREETS"

There was now growing unease about Japanese attacks on China. There were many Japanese living in Hong Kong, and there were rumours of attacks on them. One day, the blinds on our verandah were pulled down and we were not allowed to look. A Japanese family had been killed and their bodies, fixed on poles, were being paraded through the streets.

One morning, my father left as usual after breakfast. Mid-morning, his batman arrived to collect clothes and personal items. The Japanese had attacked Shanghai, and the battalion had been ordered there to protect the British concession. We watched the men march down to the docks, and that was the last we saw of my father for some time. There was some hostility among the Chinese as our men had not gone to fight the Japanese and save Shanghai, but only to protect the British concession, and we were warned to keep a low profile in case we were attacked, too.

Then came the news that we were going home. My father was to be RSM at the regimental depot at Stirling Castle. He was still away, and my mother was not well, so I was involved in all the decisions and the packing. At last it was all done, and my father was with us again as we embarked on another long voyage.'

Mairi Paterson (née Campbell, b.1921).

PERSONAL STORY: ‘NOW I WAS LIVING IN A CASTLE: STIRLING CASTLE’, 1934

In this, the final part of her account of her army childhood, Mairi Paterson recalls the time that she spent living in Stirling Castle, the regimental depot of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, to which her father had been posted from Hong Kong in 1934. (To read Mairi’s story from the start, see ‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘IT WAS A MAGICAL PLACE, WITH PALM TREES AND COFFEE PLANTATIONS’, JAMAICA, 1928–30’, above; ‘PERSONAL STORY: CROSSING THE PACIFIC, 1930’; ‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘I AM GLAD THAT I CAN REMEMBER WEIHAI AS IT WAS EIGHTY YEARS AGO’’, above; ‘PERSONAL STORY: GOING TO SCHOOL BY RICKSHAW AND KEEPING A LOW PROFILE IN HONG KONG, 1932–34’, above, and ‘PERSONAL STORY: SAILING FROM HONG KONG HOME TO SCOTLAND, 1934’.) In conclusion, Mairi relates what happened after her father retired from the regular army and reflects on having been an army child during the 1920s and 1930s.

Today, all of this is in the care of Historic Scotland, and the restoration of the palace will be complete within a few months, with tapestries on the walls and the famous carved wooden heads on the ceilings. Parliament Hall and the Chapel Royal have already been restored. However, when I lived there, it was still a barracks. The palace housed the officers’ mess and accommodation, and downstairs was the NAAFI canteen. Floors had been inserted into the soaring space of the Parliament Hall, cutting across the tall windows and making barrack rooms for the men. On the ground floor, in one corner was the NAAFI shop. The Chapel Royal was the quartermaster’s store, with tables covered with uniforms and so on.

“I WENT TO BED WITH THE LAST POST AND WOKE WITH REVEILLE”

The offices of Historic Scotland now occupy the Georgian house in the Lower Square in which we lived. It backed on to the original defensive wall of the time of James IV, and every morning I would hear the footsteps of the soldier who walked along the passage outside my window to hoist the standard. I went to bed with the Last Post and woke with Reveille.

Several other children lived in the castle – the children of the officers’-mess steward and of the civilian clerk of works. We had a wonderful time roller-skating in the Lion’s Courtyard, or Lion’s Den, and climbing and sledging in the snow down in the Back Post, which had been the original entrance to the castle.

Although it was a military establishment, the castle was open to visitors, and there were official guides. If visitors turned up after the guides had gone off duty, they were allowed in if they had come some distance. My brother and I knew the castle intimately and had heard all the stories, so we would take them around. But my father had insisted that we must never accept money for this – it was Highland hospitality. On one occasion, when we had refused money from a party of Americans, they offered us sweets. My brother had to dash off to find my father to discover whether this was allowed. The answer: one each.

The Back Post was barred to visitors as weapons and ammunition were stored there under guard. Today, these buildings house exhibitions and the tapestry workshop, and can be visited. Then, it was used a lot for recreation. The tug-o’-war team trained there, hauling a heavy bucket filled with stones up to the top of the posts supporting it.

As with all proper castles, there were ghosts. The Black Douglas rushed past the sentry at the Back Post in the guise of a huge black dog, while the officers’ mess was haunted by the Green Lady. The story was that she had been the daughter of an early commanding officer. One evening, she and her sweetheart, a young officer, were at the entrance to the castle. She saw a flower outside, and the sentry was sent to pick it, while the officer took his place. When her father saw her apparently in the arms of a private soldier, he shot her! While we were there, a batman was found unconscious in the mess and swore that he had seen the Green Lady.

When the very grand annual garden party was held in the Queen Anne Gardens, we children used to lie on the walls of the gate above and watch the guests arriving. We also watched the mess stewards as they circulated with trays of drinks and delicacies, and they usually came up and brought us some goodies.

My grandfather, who was in his eighties and had to walk with two sticks, lived with us. He had a very friendly and outgoing nature and, as a result, had a great time. “Old Mr MacLean” was invited to everything: concerts, sergeants’-mess dinners, boxing matches . . . He even went on the wives and children’s annual summer outing as a kind of honorary grandfather.

My great delight was to come back to the castle after a visit to the cinema or a friend’s party. The great gate was closed, but, as my steps sounded on the drawbridge, the small postern gate was opened and the sentry held his rifle and bayonet aslant across the opening.

“Halt! Who goes there?”

“Friend.”

“Advance, friend, and be recognised.”

I would go forward, and the sentry would move his rifle back.

“Pass, friend. All’s well.”

“OUR MILITARY LIFE WAS NOT COMPLETELY OVER”

At last, however, my father retired from the regular army, and we left Stirling Castle. But our military life was not completely over. My father left the castle to become quartermaster of the 8th Territorial Battalion (A & SH), whose headquarters were in Dunoon, Argyll. He was still there when World War II broke out, and went with the 8th to defend the Maginot line. When the Germans broke through to the north, my father, a real old soldier, got his staff safely across France to the coast by travelling, dressed in peasant clothes, behind the German Army. They got out at St Valéry, and my father was decorated for his part.

Later, my father organised the Home Guard in Argyll, and enjoyed travelling around the country he knew so well. Later still, he became beachmaster at the commando training centre that had been established among the hills and lochs near Inveraray, on the shores of Loch Fyne.

I remember it all so well and feel that I was very fortunate to be an “army brat”.’

Mairi Paterson (née Campbell, b.1921).

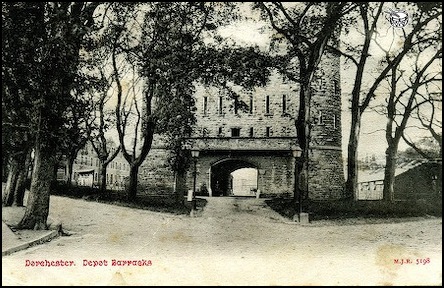

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE IN THE BARRACKS, DORCHESTER, DORSET, 1925-35

Bob Manning (b. c.1925) contributed his memories of growing up in the Dorsetshire Regiment's Depot Barracks, in Dorchester, Dorset, between 1925 and 1935 to The Keep Military Museum there. His story, as told by Helen Jones, first appeared on the museum's website (http://www.keepmilitarymuseum.org, which is well worth visiting for those with an interest in the regiments of Devon and Dorset, as well as in what life in a regimental depot was like for army children), and TACA is grateful to her, and to the museum, for permission to reproduce it.

'Local resident Bob Manning grew up in the Depot Barracks between 1925 and 1935. He remembers that much of the area of the barracks was out of bounds to the children. They were not allowed to enter the site through "The Keep" itself, but had to use the steps up to the site, situated on the Poundbury Road, opposite the cavalry barracks. They were not allowed near the soldiers' quarters either.

Above: The Dorchester Depot Barracks pictured in around 1900.

Bob lived in the "Little Keep" itself towards the end of his father's posting. Before that, the family was billeted in the married quarters. These have long been demolished, but were behind the "Little Keep" building. The married quarters were two stories high, with four or five quarters in each. There was an iron stairway at each end and a walkway between them. "Playing chase up one stairway, along the walkway and down the other staircase was strictly forbidden - not, that is, to say that the prohibition was always heeded. It was too good a chance for the boys to miss", recalls Bob. Bob remembers that the family did its grocery shopping in the NAAFI [Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes] stores on the barracks site, and that the children were often sent there on their own. Soldiers used the NAAFI to buy cigarettes and polish.

It was fun living in the barracks as a child as there were lots of places to play. There was a grass bank between the barracks and the railway. The grass was allowed to grow long before it was cut with scythes. The boys were given the clippings to make forts. The old soldiers who had fought on the North West Frontier of India taught them the word sanger, meaning "fort". Of course, the forts in India were made of stone, but the boys played out imaginary wars in their grass forts. The girls played ball games and skipping games in a grassy area near the "school" room.

The boys also liked leaving the barracks site to play on the earthworks at Poundbury. There was no industrial site there in those days, and they had to climb over a fence and cross the railway line near the railway tunnel to reach the earthworks. They would show off by "bravely" setting foot in the tunnel. At weekends, whole families would go to the earthworks, taking picnics with them. They could bathe in the river from the lower slopes. The boys also enjoyed playing along Poundbury Road itself, amongst "a rather scrubby line of trees and bushes which we called Sherwood Forest".

There were many places where the children were not allowed to go. They had to keep away from the "school" room during exams. This was not a school for children, but for soldiers. They were not allowed near the stores and offices, the officers' quarters, the officers' mess or the stables where the officers kept their horses. They were not even allowed to walk anywhere near "The Square" (the parade ground).

Bob recalls that in front of the officers' mess was a small, grassy area, and that other regiments would sometimes visit for training exercises. They would set up bivouac tents on this area. Bob can remember the Green Howards coming. The boys would try to persuade the visiting soldiers to give them cap badges, but they were not usually successful.

THE MARABOUT BARRACKS

On the other side of the road from the Depot Barracks were the old cavalry and Royal Artillery barracks known as the Marabout Barracks. Bob recalls that there was a sports field there, and that on Saturday afternoons families from the Depot Barracks would gather there to watch football and hockey matches.

There was a drill hall, too, where the children would watch the TA [Territorial Army] band practising marching and countermarching. There were workshops run by civilian staff, under the charge of a Mr Nicholls, as well. Children were not allowed to go there unless Mr Nicholls himself invited them in. They were allowed to visit the pigsties, however. The pigs were looked after by a Mr Frampton, and he was always happy to chat to the children.

There was a hospital on the Marabout Barracks site that served the families of the Depot Barracks. Colonel Sidgewick was in charge here, assisted by an NCO [non-commissioned officer] named Sergeant Lemon. All of their ailments were treated by Colonel Sidgewick, and he also gave them their inoculations.

The depot's commanding officer was Major De La Bere. He lived just outside the perimeter of the depot, but used to enter through a door in the walls. The lads were expected to raise their caps to him, should he pass them.

Bob was only about 10 years old when he left the depot, but is pleased to share his memories of growing up in Dorchester's Depot Barracks.'

PERSONAL STORY: MEMORIES OF WOOLWICH, BY AN RAF OFFICER

This piece was first published in the May 2007 issue (No. 147) of Pennant, the journal of the Forces Pension Society (see http://www.forpen.org for further details). TACA is grateful to both Squadron Leader Peacock and Pennant for permission to reproduce it.

'I am not of the army, although I come from an army family, as did my grandparents on both sides. My brothers went into the army: one to the Scots Guards and the other to the West Kents. There is always one, though . . . and I went into the Royal Air Force. This sin was never forgiven, Bomber Command notwithstanding.

My father was a Royal Engineer and an instructor at the "Shop". Our lives revolved around that noble edifice, with its highest of standards.

I well recall the last tattoo I was taken to on Woolwich Common. It was "The Storming of the Kashmir Gate" and in those days they really knew how to put on a big production.

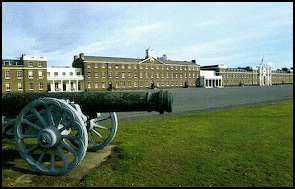

Most Sundays after church parade at the garrison church, we (my parents, two brothers and many others) would assemble on the edge of that wonderful parade ground, usually not too far from that menacing lump of gun in the foreground of the picture (see below). There we waited breathlessly for the crash of drums and the blare of brass as what was a superb military band marched out through that archway and began a magnificent display. It really prickled the skin, as it does now, just to think of it.

To the right of that long line of buildings was situated the garrison theatre. Many times did we enjoy the productions put on by the staff and others. A great treat, especially when they put on something about the "war to end all wars". It was all so exciting, so thrilling. No one thought about Hitler in that year or the repeat performance to come.

I recall several visits to the Rotunda, that sombre place, with its memorabilia of the First World War. Probably the seed of an allergy to trenches, ditches and mud was planted there.

But to remember the "Shop" and the cadets in their pillbox hats and playing bicycle hockey gives so much pleasure. My Scots Guards brother and myself were choirboys in the splendid church and I well recall singing at the funeral of General Wagstaff. Very military it was, too. I can still hear the sound of clinking medals and spurs.'

Squadron Leader Trevor Peacock.

PERSONAL STORY: EXPERIENCING TERROR AND THRILLS AT CATTERICK CAMP AND WAR'S OUTBREAK AT ALDERSHOT

TACA has sadly proved something of a letdown for this former army child, who writes: 'I have looked at the TACA website with interest, but was rather disappointed not to find accounts by army children concerned with the effects of being the child of a soldier . . . I do not propose now to give you my biography, but I thought that an example or two of my own banal experiences as an army child might encourage other army children to follow suit. I hope that these few memories of mine, as an army child, will encourage other army children to share some of their experiences with the rest of us.' We should, perhaps, say in response, firstly, that those with an interest in history would not agree that the following recollections are in any way banal, and, secondly, that similar memories would indeed be very welcome.

'I was born in Catterick Camp, in the army hospital there - a wooden building, as it was then. My father was posted to Aldershot when I was about four or five, so until then I lived in a completely military environment. I can remember very little of that time, but I do still recall being terrified of pipe bands, which often marched past our quarter. If I shut my eyes, I can see the serried ranks of white spats worn by the bandsmen. Another source of terror for me was tanks. They really scared me, rumbling by. I think it was the clatter of the tracks and the (to me) enormous size of these unwieldy vehicles. These frights, and many similar ones, were probably not everyday experiences, but, in Catterick Camp, pretty frequent.

On a brighter note, I can remember being very impressed by a display by the Royal Signals, as I now know them to have been. This was the thrilling sight of the dispatch riders mounted on their motorcycles, leaping over horse-drawn cable wagons as they circled the arena in the opposite direction. Of course, military dispatch riders and cable wagons were an everyday sight in Catterick Camp in those days, and, to an army-child infant, perfectly normal; I only remember them because of the leaping motorcycles.

Aldershot was a very different environment. It was a large town, and the army garrison was mainly on the outskirts. My father had bought a house near the railway station, so we did not live directly in an exclusively army environment. However, as an army child, one regarded civilians as "different", and I felt quite at home when going through the barracks, gazing at the horses in their stables and cadging army biscuits from the various regimental cookhouses. We attended an army doctor's surgery and an army dentist's surgery, an army church and, when necessary, an army hospital - a separate one for wives and children. We bought our food rations from the NAAFI shop.

Above: Aldershot Camp, Hampshire, as it looked during the early decades of the twentieth century.

Two events remain particularly in my memory. The war (I heard the declaration on the radio), of course, was probably more noticeable in a large military garrison, especially as we lived near the station, but was brought home to me particularly vividly when, one day, I found the town absolutely swamped by exhausted soldiers fast asleep on the pavements, in all manner of dress, and without their equipment. These were the survivors of Dunkirk, who had been packed into trains on the coast and sent to Aldershot. My mother and many other ladies carried around tea and sandwiches for them. They were soon housed in the barracks, of course, but it was a shock to a small boy to experience the less glamorous aspects of war.

One more Aldershot memory: one Sunday, on going to church (the Roman Catholic one), we found it packed full of French Canadian soldiers, a church parade. That was a bit of a shock, but a pleasant one, since it brought home to me that our country was not alone. I am surprised that I can still remember it so well, but this is probably because it was a very personal experience.'

JRG (b.1929).

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: REQUEST FOR INFORMATION ABOUT A ROYAL ENGINEERS OFFICER AND IMAGES OF RANIKHET, INDIA

Jon Alexander has sent the following message requesting information and images relating to wartime India.

‘I was born at the British military hospital (BMH) in Ranikhet (India) in May 1942. My father, Peter Alexander, was a lieutenant (then a major) in the Royal Engineers, with postings in Bombay, Bangalore and Madras during the 1939–1946 period. If anyone has information or memories concerning my father during this time, I will be pleased to hear from them via TACA. If anyone can contribute photographs of the BMH in Ranikhet at that time (or now, if it is still in use), or of St Peter's Church (Ranikhet), where I was baptised, I shall be most grateful.’

If you have any information, memories or photographs that you think will interest Jon, he can be contacted through TACA.

NEW RESEARCH PROJECT: DOCUMENTING BRITISH ARMY CHILDREN’S EXPERIENCES OF VERDEN, GERMANY, 1945–93

TACA has received the following call for contributions from Anca, a German researcher who is resident in Verden, a town in Lower Saxony, Germany.

‘I am writing a history of a period of our town’s history entitled "BAOR: The British Garrison of Verden (Germany), 1945–1993”. One chapter of my research project is devoted to the education and everyday life of British army children in Verden at this time.

I initiated my research project because my own children (born in the early 1990s) know next to nothing about the presence of nearly 4,000 British people in Verden from 1945 to 1993. I therefore want to ensure that the history of these temporary residents of our town is documented and remembered.

I am therefore very interested in the memories of those British army children who spent part of their childhood in Verden. I would particularly like to understand more about their everyday lives. Did they have contact with their German peers, for example, perhaps in the playground or through sports and clubs, or did they experience their Verden army childhood living completely separately from the people of Verden, that is, did they effectively live a parallel existence?’

If you think that you can help Anca in her immensely worthwhile task, please e-mail her at karli60@gmx.de. All contributions will remain anonymous, documenting the contributor’s year of birth being the most important consideration. (And see below for an update.)

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: DOCUMENTING BRITISH ARMY CHILDREN’S EXPERIENCES OF VERDEN, GERMANY, 1945–93 – AN UPDATE

Some time ago, we posted a request from Anca, who is researching the history of Verden, the German town in which she lives, for any army children who lived in Verden between 1945 to 1993 to share their memories of this post-war British Army garrison town (for further details, see above, ‘NEW RESEARCH PROJECT: DOCUMENTING BRITISH ARMY CHILDREN’S EXPERIENCES OF VERDEN, GERMANY, 1945–93’). Anca has now updated us on her project:

‘Your announcement on TACA allowed me to make contact with a few British alumni who spent a part of their life in Verden, at different periods.

So I got different experiences, different opinions about their army childhood and wonderful pictures, too. This is very helpful for my project and I was especially glad to receive personal memories sent to a stranger, a great sign of confidence.

I learned that ex-army children are now scattered all over the world. I received e-mails from the UK, Australia and the USA! The numerous postings of their fathers seems to have made the children very cosmopolitan.’

Anca’s project remains ongoing, so if you would like to share your memories of Verden with her, please e-mail her at karli60@gmx.de (as before, all contributions will remain anonymous).

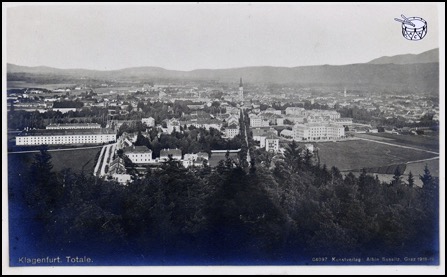

PICTURE: KLAGENFURT, AUSTRIA

The postcard below presents a view of Klagenfurt, the capital of the Austrian province of Carinthia. Many British army families lived in Klagenfurt while it was designated the headquarters of British Troops in Austria (BTA), i.e., from 1945 to 1955.

PERSONAL STORY: ‘IT IS ETCHED ON MY MEMORY, THE DEVASTATION’, HAMBURG, (WEST) GERMANY, 1948

Brian Spurway has most kindly contributed two evocative photographs to TACA, which were taken in north Germany in 1948. The first was taken in Hamburg, and the second, on the island of Norderney. As Brian explains, his was an RAF family, but their army counterparts would have shared their experience of Hamburg:

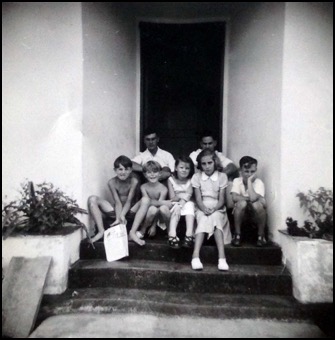

‘In 1946, my father, then a RAF flight sergeant, was stationed at Klagenfurt in Austria. My mother, brother and I joined him there later that year. In the terrible winter of 1947, he was posted to Hamburg, to No 5 MTBD [Motor Transport Base Depot], where we three joined him as soon as a married quarter became available; that being in a block of flats on Alsterdorfer Strasse. Most, if not all, of our close neighbours were army families. The photograph I attach is of children from some of those families at a birthday party in one of the flats; whose party it was, I cannot remember, but I am the nine-year-old with his elbow on the table – how my mum used to nag me for that! I would hazard a guess that the gentleman on the right was the birthday child’s father. It would be marvellous if someone reading this could recognise himself, or herself, or, indeed, anyone else in the photo; I remember only the faces.

The block of flats we were in had once been just one of probably four or five such blocks, but at the time we were there, it was just one of the two surviving after the massive bombing of Hamburg. It is etched on my memory, the devastation between where we lived in Alsterdorfer Strasse, just a short distance from Fuhlsbüttel Airport, and the city itself. I still see us playing in the bombed-out remains of the blocks that had been destroyed, and finding remnants of personal belongings that had once belonged to the occupants. All through my secondary schooling, and for years afterwards, I used a Tintenkuli fountain pen that I had found amongst the ruins – lost later, sadly.

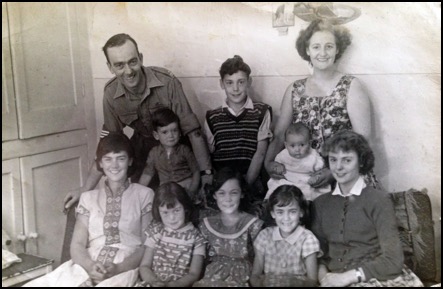

The photograph above is a holiday snap that was taken on the beach at Norderney, where we stayed in the summer of 1948; it’s not a great photo, with its age and the sepia look, but it certainly conveys atmosphere and history. I remember it being very hot there that year, but with a very strong wind constantly blowing in off the sea, hence the basket-weave “deckchairs” in use by the adults. The family of four on the left was called Minty, and they must have lived in a flat near ours as the elder son also appears on the birthday photo sitting on my left. My father and mother are in the centre, with me sitting on the sand and my younger, by two years, brother, Ian, standing up in the fetching black woollen bathing suit. The couple on the right, whom I remember as being childless, were called Judd, and I well remember them living in a flat very close to, in fact, overlooking, I’m pretty sure, the school I attended in Altona. I recall that we all stayed in a rather nice hotel, and also that, with fathers in attendance, we boys had great fun exploring what I can only imagine were Second World War German fortifications of some sort.

I had learnt to ski whilst in Austria, and I recall our taking a winter holiday later that year at a place called Bad Harzburg, again staying in a very smart hotel; sadly, I have no photographs of that holiday. I do remember spending most of my time on the ski slopes and also seem to have, somewhere in the back of my mind, the knowledge that we were sometimes very close to the border between East and West Germany – am I only imagining it, or do I truly remember seeing East German border guards patrolling that border?’

Many thanks to Brian for sharing his photographs and memories. And if you recognise anyone in his photographs (maybe even yourself), please e-mail TACA, and we’ll pass on your message.

PERSONAL STORY: MEMORIES OF POST-WAR BERLIN

When, a few years after the end of World War II, Mrs Elizabeth Robertson, the daughter of Major General Geoffrey Kemp Bourne (later General the Lord Bourne, GCB, KBE, CMG), moved to Berlin with her family, the former and future capital of Germany was divided, with the Soviet Union occupying East Berlin and the American, British and French sectors constituting West Berlin. Although the Berlin Wall had yet to be constructed, relations between the Soviet Union and the Western powers were becoming increasingly hostile, contributing to the Soviet-imposed economic blockade of West Berlin. This lasted from June 1948 until May 1949, and was circumvented by the Berlin Airlift that Mrs Robertson recalls below. Mrs Robertson's reminiscences originally appeared in the May 2008 issue (No. 149) of Pennant, the journal of the Forces Pension Society (see http://www.forpen.org for more information), and TACA thanks Mrs Robertson and Pennant for permission to reproduce them.

'My father took over the job of British Commandant in Berlin from General Herbert, when the airlift was already in train, and it then continued for some months. The planes flew constantly non-stop over our house and, together with the French and Americans, kept the city alive.

I offer some memories of that time: the lovely house and garden on the outskirts of the city, sloping to the edge of Lake Havel, and which I think belongs to a German industrialist; summer parties on the terrace; a garden party for displaced persons from the Russian Sector; sailing on Lake Havel; and on the opposite side the woods and beach enjoyed by Berliners; the grey grimness of much rubble still; and no entry to the Russian Sector except by strict permits, some for permission to go to the opera. Hitler's Bunker and Spandau Jail, and, of course, the famous Olympic Stadium; overnight journeys by train from Berlin to the British Zone and vice versa, and sometimes by car down the autobahn through the Russian Zone without stopping.

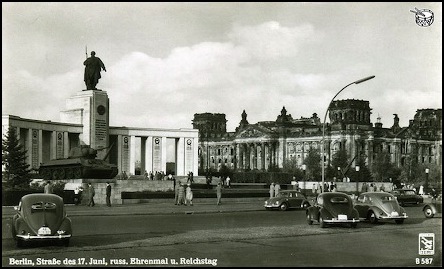

Above: A postcard, dating from the 1950s, showing the Soviet War Memorial on the Straße des 17. Juni, in West Berlin's Tiergarten district (in the British Sector), and the ruined Reichstag.

The British way of life had to be separate, with its own currency, bus transport etc. The only leeway I had was once or twice to visit the home of my music teacher in the American Sector (she had two harpsichords, which took up most of the room) and to go with her to a carol concert in a large church in the Kurfürstendamm, which was unforgettable.

An erstwhile ADC of my father's went back in recent years to the house we lived in and found little had changed and received a warm welcome. My mother took great care and delight in the garden, and the large greenhouse was full of cyclamen plants in the winter, which could either be piled into the house or even picked, there were so many. I often think the German gardeners must have been consoled by such enthusiasm, the results of which contrasted so greatly with the surrounding circumstances of hardship and deprivation and such destruction in the city. Although I learnt German, it is my regret that I was unable to go around freely except on an occasional bus.

Plainly my father did his very best for the people of Berlin, and they were immensely grateful. Although I did not know it at the time, he resurrected the Tiergarten with seeds specially chosen for the soil and collected in Britain, and he also built a church for the British community.

I am sure that some of you reading this will have other and completely different reminiscences, and will remember far more than I have written here.'

Elizabeth Robertson (née Bourne).

PERSONAL STORY: BERLIN, 1948 TO 1951

In the following account, Tim Sanders describes the excitement of travelling from England to Berlin in 1948, and of settling into a war-devastated city that had been divided into four sectors controlled by the four occupying powers. He continues by describing the life that he led as an army child in West Berlin – then a frontline city on the very edge of the Iron Curtain – at the start of the Cold War era, until his father was posted away.

'I was born in Hertfordshire in 1944, was evacuated to Wales and then lived with other family members in Kent and Guernsey after the war ended, our house in Finchley, north London, having been destroyed by bombing. Indeed, my first flight ever was at the age of three, when I flew in a De Havilland Rapide biplane from the then Croydon Airport to Guernsey, to live with my maternal aunt for several months; the eventual return to the mainland by boat to Weymouth was a distinct anti-climax. All this time my father was still serving abroad in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, transferring in 1947 to the Royal Tank Regiment. We were living in Farnham, Surrey, when he was posted to Berlin, and we were to follow.

The route was from Farnham to London Waterloo Station, and then to Liverpool Street Station for the boat train to Harwich Parkeston Quay. After that, it was by overnight boat to the Hook of Holland for one of three military trains taking military forces and their families to selected areas of BAOR (British Army of the Rhine). For those going to Berlin, it would take all day, from 0700 to 1730, to reach the border between the British Zone and the Russian Zone at Bad Oeynhausen. A change of trains here, with a short stay in a local hotel, would be followed by a journey on the sealed and guarded overnight sleeper train through the Russian Zone, reaching Berlin at around 0600. The train consisted of only a few coaches, guarded by an officer and several men, all armed, and with live ammunition. So it was to be a long journey, and it was very exciting for me to be going abroad for the first time.

I have a range of particular memories of this journey. They start with the dark and dingy recesses of Liverpool Street Station: smoke and the smell of hot engines, steam and bustle, hot metal, whistles blowing, doors slamming and the dimly lit compartment booked for my mother, my younger brother of only a few months of age, and me. Then the dingy cabin, somewhere in the depths of the ship, allocated to the three of us, followed by the bitter cold of the Dutch morning air as we walked 200 yards from the ship to the waiting train, through military police and immigration checkpoints. I think that the "Berlin" train was Train A. We had our own six-seat compartment, and for me the big attraction was the huge picture window so that I could see everything much more easily than from British carriages.

The seemingly endless journey, at never more than slow-to-medium speed, took us across flat Holland into Germany. We passed tens of miles upon tens of miles of wrecked rolling stock, some already rusting, with bullet holes plain to see, some semi-burned out, all seemingly parked to await their eventual fate, and all clearly looking to me, even at that young age, wrecked beyond further use. I was very glad to have my big window to look out of because the corridor down the other side of the carriage was always full of soldiers in their khaki battledress uniform. They came from various organisations, many of them with white-lettered-on-red-background shoulder flashes giving the titles of their units or service. They were all smoking, so it was very stuffy walking down the train for the meals that we had in the open-spaced dining car.

By the time we reached the evening pause point at Bad Oeynhausen, I was thoroughly exhausted, and I can just remember tumbling into the bed in the sleeper train – again, a first for me. The blinds were supposed to be kept down all the time that we travelled through the Russian Zone, but I remember that the jolt of the train stopping woke me up in the middle of the night and that I then decided to have a peek out of the window. However, all that I could see was a poorly lit platform with nobody there – and the next thing I recall was arriving in Berlin to drive some distance to the requisitioned family house in Charlottenburg, a well-to-do residential suburb in the British Sector of the city. Number 10, Warnen Weg, had escaped the bombing – and is still there as I write today (in 2008). Even at that early hour of the day, I remember that many of the buildings that we passed were in ruins, and that in some streets it was necessary for our vehicle to drive in a series of "S" bends in order to keep moving forward. It was a day or so before I had recovered from what was, for me, a very exciting journey, but some 60 years later, I still love travelling internationally.

SETTLING INTO A PARTITIONED CITY

Warnen Weg, in Charlottenburg, was only about 10 minutes' walk from the British Officers' Club, and also from the NAAFI Families' Shop. That was on a big roundabout, then called the Reichskanzlerplatz (literally "Reichs Chancellor Place" in English), but since renamed in order to be politically correct in the post-war era. Warnen Weg itself was seemingly a long road in my memory, but I was then a small boy, and it is, in fact, only about 100 yards long. The houses at each end of the road had been completely or partially destroyed, and as a small boy, you could wander in and out of them at will. One bungalow had housed an architect's business and contained hundreds of building plans, as well as all of the normal household contents. Several other army families lived in Warnen Weg, most of the fathers being captains or majors.

Our four-bedroomed house in Warnen Weg is still there today; it would be some 25 years later, in the second half of the 1980s, that I would revisit it. We had a large staff as a contribution towards raising employment levels amongst the Berliner population and getting the economy back on its feet. I don’t know what they were paid, but the fact of a job was an obvious morale-booster. We shared our boilerman with No 6 and No 8, the coal-stoked boiler being vital in winter. I suppose that he slept in one or all three of the houses – he didn't have his own room in the basement. We had a live-in cook/housekeeper, a kindly lady called Herta, whose family had all been killed. Herta had one day off a week and she lived in the attic level of the house. We also had a cleaning lady who would come in some days a week – and all of this for my father's rank as a junior captain. But these were very unusual times, of course. I remember vividly the huge double radiators under the very large, double picture windows that kept the house airy, yet warm, in the winter. The window handles were too heavy for me to operate. I started my stamp collection in Berlin. German stamps with face values of millions of marks from the 1930s' period, when a suitcase of banknotes was needed to buy a loaf of bread, were still very easily obtainable from the few stamp dealers in business then. I would walk to the NAAFI shop to buy my latest stamp collectors' magazine, much of it above my head, but you had to start somewhere; then I would sit at home by the big radiators in the winter sunshine to read up on the latest news.

Winter in Berlin could be very cold indeed; it is easy to underestimate how far east Berlin lies, and its relative proximity to Siberia. One day, I was outside in brilliant sunshine for over two hours, without any protective hat, and the wind-chill factor must have been very high. I got second-degree frostbite on the edges of my ears, and every summer for at least 20 years after that my ears would blister and peel in the summer sun.

My father was a captain, the second-in-command of the Royal Tank Regiment's "Independent" tank squadron, a token presence in Berlin of some 15 to 20 tanks, surrounded as the city was by the Russian Zone, then containing thousands of Russian troops and, no doubt, hundreds of tanks in numerous tank divisions and mechanised infantry divisions. I expect that the Americans and the French had some tanks, too, in their respective sectors of Berlin, but I never saw them. The British Sector contained Spandau Prison, where the British forces had the rotational task, shared with the other Allies, of guarding Rudolf Hess. I suppose the token British tank squadron was an early forerunner of tripwire diplomacy as it wouldn't have lasted five minutes against the Russians. There was a real concern amongst the adults regarding what the Russians could do if they chose to, but like many other such very real threats, we lived so close to it every day that we tended to ignore it in favour of getting on with day-to-day events. This was so even in 1950, when memories of the Berlin Airlift of the previous year [June 1948 to May 1949] were still crystal clear.

These were pre-Wall days, and you could visit the Russian Sector of Berlin out of sheer curiosity. The reader should remember that the Russian "Zone" that surrounded Berlin was the region that began once you reached the "outward boundary" of each of the four "sectors", i.e., the British, American, French and Russian Sector respectively. The Russian Sector's border with the other three sectors was also the border between West Germany and East Germany, so in order to buy anything in the Russian Sector, you had to obtain East German Deutschmarks. The rate of exchange was 4 East marks to 1 West mark, but the point was that only three items were really worth buying. Firstly, there were the carved Russian dolls in wooden, brightly painted "nests", probably three or four dolls to a nest, which would be about 6 inches high at the most. Secondly, 33 rpm long-playing records by Polydor of classical music were popular with the adults, for those that had record players (we didn't have one). Thirdly, tickets for the East German opera house were popular for monthly visits by the British (my parents went occasionally). I saw my first Russian soldiers at the daily guard-changing ceremony at the Soviet Army War Memorial (pictured at left in 2007) in the Russian Sector.

You could also pass through the Russian Sector by taking the S-Bahn (the "S" stands for both Stadt, or "city", and Schell, or "fast", in German, an English aide-mémoire being "S" for "surface") suburban train, or a U-Bahn ("U’ standing for Untergrund, or "underground") train. The various routes for these trains crisscrossed between the fringes of the Russian Sector, on the one hand, and the other three Allied sectors, on the other hand. You had to be very careful indeed not to alight from these trains within the Russian Sector because to do so as a family unit without a uniformed Allied forces member present was strictly forbidden, and would have caused a local incident of considerable proportions. It always felt a bit worrying when transiting these bits of the Russian Sector, but nothing ever went wrong for us.

I have a strong recollection of the pungent smell of cigars that was always present in public places, especially on buses, trams and trains. ("No smoking" carriages hadn’t been thought of yet.) The same smell was ever present in the concrete fortifications that still lay everywhere, wide open to inquisitive investigation by a small boy such as me. (I had experienced this before on Guernsey, in the massive towers and bunkers built there by the Germans.) It was as if the smokers had left only yesterday.

My father obtained for virtually nothing a former Mercedes-Benz four-seater staff car as a family car. It had a brown fabric roof that folded right back and rested on the rear of the back seat. It was coloured medium green, had very big headlights, a big wooden steering wheel and looked very grand. There was a Union-flag metal badge on the front and back bumper, as required by Allied occupation rules. It would be a classic car if it was around today in 2008, and was exactly the model that senior German Army officers had used in Hitler's army. Petrol was rationed somehow, and as most places that one needed to reach were within walking distance, the car was normally used at weekends only.

We used to go sailing at the British Officers' Yacht Club at RAF Gatow, on the river Havel, in the forested area called the Grunewald. This is one of the "green" areas of Berlin and is still there today. The river widens out to some 984 feet or more, and there was plenty of space in which to sail. I learned to sail in Berlin, mainly in a four-berth Bermudan sloop about 35 feet long, known as a "One Hundred Square" because that was the area of its mainsail. There were two or three of these large yachts and a further dozen or so half-decked racing yachts, known as the "Star" class, all requisitioned from German sources.

There was an island that we used to circumnavigate about 30 minutes from the moorings; such a sail took most of the day because the wind direction required many changes of course rather than a simple, straight-line approach and return. The Pfauen Insel (Peacock Island) lay beneath a rocky promontory on the river bank, which had a Greek Orthodox church on top of it. At midday daily, the bells of the church tolled out the melody "Now Thank We All Our God". You had to be careful when going around the island to keep well inside a line of yellow buoys marking the line of the Russian Zone (not the Russian Sector) across the river Havel. Once one of the "One Hundred Squares" caused an international incident in daylight by crossing the line and continuing onwards. It was rewarded with a burst of machine-gun fire through the mainsail, albeit well above the heads of the crew. It was only then that the yacht went about and returned to the right side of the border.

The back of the sailing-club building was on the Russian Sector's border, I think. On occasions, cases of vodka would be handed through a back window by a Russian in exchange for cases of whisky handed back by a sailing-club member.

I drank my first ever Coca-Cola at the US Officers' Club, which seemed to me to be a very grand building in comparison to the single-storey British Officers' Club. I will never forget the look and taste of this fizzy, dark-brown, sweet liquid, chilled to a very suitable coolness and very delicious. It was a great change from the usual fizzy ginger ale that was the only special drink available as a treat for a small boy at the British Officers' Club.

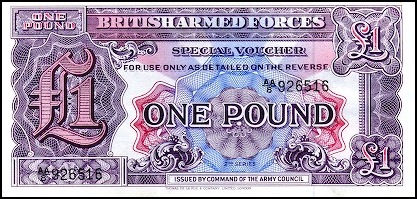

Our chief food supply was the daily ration truck; it being 1948, rationing applied here just as it did in England. A cardboard box provided our staple food for 24 hours. There was always greengage jam – no other flavours. (In later life, I became a marmalade gourmet in retaliation!) Buying food in the few food shops that were open in the city was subject to very strict rules, not to mention the intermittent availability of the food itself. Dairy produce of any kind was strictly forbidden as the hygiene system was still being re-established. Vegetables could only be bought at certain open street markets or shops, all listed officially. In any case, you needed West German Deutschmarks to buy anything in the city; the army issued you with British Armed Forces Vouchers (BAFVs), which were paper money. There was even a 3-penny paper note as the smallest-denomination paper money within the BAFV range; it was about the same size as today's 5-euro note and it was coloured a sort of orange brown. My pocket money was 1 shilling a week, so the 3-penny note was important to me as a quarter of my weekly income.

Above: A £1 British Armed Forces Special Voucher (2nd series, issued in 1948).

If my mother took me to the shops other than the NAAFI, we used to get a snack consisting of a Bockwurst (a boiled sausage) and a bread roll with mustard. These were available from a multitude of little stalls on wheels that were very much a part of the street scene then, standing on many of the corners of main street intersections in the city centre. Heaven knows what was in the sausages, but they never did us any harm and they were a huge relief after the British rations – especially the dreaded greengage jam!

When shopping, we used to visit the well-known department store called KaDeWe (pronounced "KarDayVay") quite a lot. The name is an abbreviation of the words Kaufhaus des Westens ("Department Store of the West" in literal English translation). I don't know how much of the bombing it escaped, but it certainly must have been one of the first shops to be reinstated as it had always been a focal point on the Tauentzienstraße, adjoining the main shopping street, the Kurfürstendamm – rather like Selfridge's position on Oxford Street, London. In my day, it had four floors; today, in 2008, there are six or seven. The presence, and reasonable stocking, of the shop was very much one of the key demonstrations by the Berliners of their determination to get back on their feet after the war, and I know from comments made by our house staff of Berliners that they were proud of the fact. It was only 100 yards or so from the famous Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtnis-Kirche, the bombed church whose remains stand today in the centre of the Kurfürstendamm as a memorial to the destruction of World War II. On the top floor of the KaDeWe (pictured at right in 2007)