When committed to paper, army children's memories often make interesting reading, including, maybe yours, or some that you have read. There follows a small selection.

'My father was a native of Scotland, in the [East India] Company's service; my mother was a Rajpootree, the daughter of a zamindar . . . who was taken prisoner at the age of fourteen . . . My father then an ensign into whose hands she fell, treated her with great kindness, and she bore him six children, three girls and three boys. The former were all married to gentlemen in the Company's service; my elder brother, David, went to sea; I myself became a soldier, and my younger brother, Robert, followed my example.'

Lt Col James Skinner (1778-1841), quoted in Dennis Holman, Sikander Sahib: The Life of Colonel James Skinner, 1778-1841, London, 1961, pp.213-14.

'I remember my father leaving the house and then checking under the car for a bomb before driving to work each morning. This was during the late 1970s, when the IRA was targeting British soldiers serving in Germany.'

TD (b.1964).

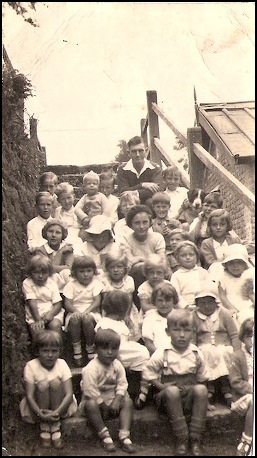

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: DO YOU RECOGNISE YOUR YOUNGER SELF?

Michael Few has sent TACA a family photograph (shown here) with a request for help: 'If anyone recognises themselves in this photograph, I would love to hear from you'.

The photograph shows Michael's father, John Few, who was in the Royal Signals, sitting on some stone steps with a large group of children aged between around two to seven years. Written on the back is 'My gang, Sept 1935, Katapahar, Darjeeling, Bengal'. Michael thinks that his father's duties may have included acting as a caretaker at a school in Katapahar, and is keen to learn more. If you can throw further light on the photograph, please e-mail TACA.

PERSONAL STORY: WARTIME IN EGYPT AND SOUTH AFRICA, PEACETIME IN ENGLAND AND SINGAPORE

This army child spent much of World War II in Egypt and South Africa, and later lived in England and Singapore.

'My name is Daisy Caroline Blythe, née Parris, and I was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1937. My father, Alfred Leonard James Parris, was in the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) and married my mother, Georgette Eugenie Youssief, who, according to her birth certificate, was Palestinian, although she, too, was born in Alexandria, Egypt. (Incidentally, all my mother's family were Roman Catholics.)

In 1942, my mother and her children were evacuated to South Africa; my father stayed in Egypt. We were all reunited after World War II.

I have five sisters, including: Valerie, born near Cairo, Egypt (1938); Leonora, born in Palestine (1940); and Christine, born in Alexandria, Egypt (1947); the last two were born in the UK.

We returned to the UK in 1947. After docking in Liverpool, we stayed in a hostel on Lime Street Station (in transit). After that, we were sent to the Isle of Sheppey (in transit).

I met my husband, Gordon (also RASC), when my father was posted to Singapore. We married in Singapore in 1954 and we had four children. My birth certificate and marriage certificate are both army forms.

We have been living in Altea, Spain, since my husband's retirement in 1993.'

Daisy Caroline Blythe (née Parris, b.1937).

PERSONAL STORY: WARTIME IN THE UK; PEACETIME IN MALTA, EGYPT AND OXFORDSHIRE

Chris Fussell's army-child experiences included being billeted in a barn in Northern Ireland and witnessing joyful VE and VJ celebrations in Aldershot. Read on to learn more, and see 'PERSONAL STORY: 'EVER HEARD A SHOT FIRED IN ANGER?'' and 'PERSONAL STORY: BULLFROGS, CICADAS AND MACHINE-GUN FIRE IN EGYPT, 1951' on the 'LIVES & TIMES' page; 'PERSONAL STORY: A MARRIED-QUARTER CRISIS IN EGYPT' on the 'ACCOMMODATION' page; 'PERSONAL STORY: EXPERT FIRST AID IN MALTA', and 'PERSONAL STORY: MAYHEM IN A MALTESE MARRIED QUARTER', below; and the 'SCHOOLING' page ('PERSONAL STORY: MY EDUCATION AS A MARRIED-QUARTERS’ CHILD').

'My dad was a pre-war regular soldier, Royal Warwicks [the Royal Warwickshire Regiment]. He enlisted in 1926, as a starving miner, after the General Strike. He served in Palestine and India (where my sister, Brenda, was born in Poona, in 1935; Alan, my brother, was born in 1930). He rose to be a lance sergeant in the Warwicks' signal platoon (heliographs and semaphore, a few new-fangled radio sets?) by 1939, and was ex-officio keeper of the regimental-mascot antelope. He was severely injured at the start of World War II, but was kept on as 'medically downgraded' in extra-regimental work, away from his beloved regiment, until, eventually 1956!

I was born in Taunton in November 1939. I do not remember it much, and we moved on as Dad became, sadly miscast, a military prison warder in MPSC [the Military Provost Staff Corps]. I remember Northern Ireland vividly, where we lived in the country, near Carrickfergus. There were no married quarters there, so the family – Mum and three kids – lived up a ladder in a farm barn. My first girlfriend, Hazel Clark, aged three, lived next door. (An older woman!) I do recall slow, wartime train journeys; people living in the Tube stations in London; houses in Liverpool backing on to the railway line split open like dolls' houses, with furniture falling out; being sick on the ferry boats; Mum putting a rather oversized toddler (me) into a pram to push me over the Irish Free State border to buy unrationed bacon, butter and eggs, and then wheeling the pram back, with me sitting precariously on top, past winking Southern Irish and Ulster policemen at the border crossing.

Then came Aldershot, North Camp, actually from 1944. Dad was a staff sergeant by then, supervising the cookhouses in the legendary 'Glasshouse' military prison. I recall three or four events of note. There were no school dinners then, so we all spent about ninety minutes' dinnertime at home every day. A test pilot from the neighbouring Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, crashed a captured German jet plane into the school! There was no school for a while. VE [Victory in Europe] and VJ [Victory in Japan] days – hilariously happy Canadian soldiers touring the area in dazzle-painted jeeps, throwing loads of sweets and toys to the kids in married quarters; Hitler and swastikas and rising suns (for Japan) burning in effigy on huge bonfires. Later, prisoners rioted and set fire to the jail and then sat on the glass roof waiting to be rescued! (Oh, and the sky did go black with planes and gliders once – our lot en route to the Rhine crossing in March 1944?)

Then, in 1947, Malta: sun, sand and swimming. My sailor Uncle Jack coming up from his minesweeper in the Grand Harbour with presents for us from all over the Mediterranean. In 1949, a drab married-families' transit camp back in Hull. Dad left the army briefly, then re-enlisted in the RPC [Royal Pioneer Corps].

Fast-forward to 1951–54, and the Egyptian Canal Zone. Nice flats in Ismailia; riots in 1951; and then quarters in Moascar Garrison. More sun, swimming and sand. My sister could not wait to leave school and worked on the garrison telephone exchange. There was an excellent army children's school, a sort of 'proto-comprehensive' really. I was doing O' level GCEs at the age of thirteen.

Then it was back to reality and Bicester, Oxon, in 1954. Dad's last days in the army. I went to Bicester Grammar School. The girls (I had discovered girls by the age of fourteen!) were all gorgeous and had accents just like Pam Ayres'. (Every time I hear her now on the radio, I’m reminded of the back seat of the school bus.)

I had dreams of "joining the army and learning a trade" (a recruiting slogan of the day), doing my eight years and then investing my gratuity in a nice little radio shop in the corner of Bicester's Market Square (and maybe settling down with Heather from the hairdressers', next to the butcher's shop where I worked part-time after school). Anyway, I went to the Army Apprentices School, Arborfield, in 1954, where by chance I met some "army brats" I'd met before around the world. End of life in married quarters for me?’

Chris Fussell (b.1939).

PERSONAL STORY: EXPERT FIRST AID IN MALTA

Chris Fussell was living in Malta when, as he recounts below, he found himself benefiting from some expert bandaging skills honed during World War II. To read more about his life as an army child, see above, 'PERSONAL STORY: WARTIME IN THE UK; PEACETIME IN MALTA, EGYPT AND OXFORDSHIRE', and below, 'PERSONAL STORY: MAYHEM IN A MALTESE MARRIED QUARTER', and visit the 'LIVES & TIMES' page ('PERSONAL STORY: 'EVER HEARD A SHOT FIRED IN ANGER?'' and 'PERSONAL STORY: BULLFROGS, CICADAS AND MACHINE-GUN FIRE IN EGYPT, 1951'), as well as the 'ACCOMMODATION' page ('PERSONAL STORY: A MARRIED-QUARTER CRISIS IN EGYPT') and the 'SCHOOLING' page ('PERSONAL STORY: MY EDUCATION AS A MARRIED-QUARTERS' CHILD').

'I was attending Sunday school in the Royal Navy dockyard a bit unwillingly. At eight years old, I just wanted to go to the beach! As soon as school was out, I ran for the (glass) doors and stuck my hand out to open them. But my aim was bad, so my hand hit not the doorframe, but a glass pane! So there I was standing there, with my forearm through the door, dripping blood. I couldn't cry – girls, including my big sister (aged twelve), were watching.

A sympathetic chaplain eased my hand out, took me to the vestry and proceeded to "débride" the wound with a very stiff scrubbing brush and cold water. A clucking lady gave me a glass of milk, which I threw up. He slapped on iodine, seemingly by the pint, and bandaged up my arm tightly (a technique that he had learned on the Malta convoys, he rather boasted).

I must have missed the clucking lady when I was sick because she ran us home in her Austin 7, a trendy runabout in those post-war (1947) days. My sister cringed away from me on the back seat for fear of getting iodine or blood on her Sunday dress. Mum scolded me in the kitchen of her little MQ [married quarters] in Corradino and insisted on unwrapping the chaplain's handiwork. She almost fainted at the sight of strips of flesh hanging off my arm. Dad, who was ever underrated in our family, said "Don't be soft, woman!" and snipped off the fragments and repeated the chaplain's dressing – tighter! (He had dealt with casualties on the road back to Dunkirk in 1940, but he never talked about that.)

Two hours later, having skipped Mum's lunch, we were on the beach at lovely Ghajn Tuffieha (today renamed "Golden Sands" or some such for tourists?). I was half-dressed as I tucked into eggs and chips from the beach café. Ever practical, Dad inflated an old motorbike tyre so that I could float on the water, if not swim, secured, tethered to a rock, by our spare clothesline. My sister had stopped moaning. Happy, happy days!'

Chris Fussell (b.1939).

PERSONAL STORY: MAYHEM IN A MALTESE MARRIED QUARTER

Chris Fussell's tale of the night that his family's dogs ran amok on Malta highlights the contact that many army children had with former enemies – in this case, German soldiers turned prisoners of war – in the years immediately following World War II. To read more about Chris' life as an army child, see above ('PERSONAL STORY: WARTIME IN THE UK; PEACETIME IN MALTA, EGYPT AND OXFORDSHIRE' and 'PERSONAL STORY: EXPERT FIRST AID IN MALTA') and visit the 'LIVES & TIMES' page ('PERSONAL STORY: 'EVER HEARD A SHOT FIRED IN ANGER?'' and 'PERSONAL STORY: BULLFROGS, CICADAS AND MACHINE-GUN FIRE IN EGYPT, 1951'), as well as the 'ACCOMMODATION' page ('PERSONAL STORY: A MARRIED-QUARTER CRISIS IN EGYPT') and the 'SCHOOLING' page ('PERSONAL STORY: MY EDUCATION AS A MARRIED-QUARTERS' CHILD').

'Our home in Malta between 1947 and 1949 was a nice little sandstone bungalow in the shadow of the old ramparts of the fortress city of Valletta. The place was called Corradino, the nearest town being Pawla. One of the forts in those ramparts had been converted into a tri-service detention barracks for offenders from the RN, army and RAF. Due to disability, Dad had been seconded away from his beloved regiment, the Royal Warwicks, as a prison officer, and he was a reluctant "screw". There were five of us initially when we went there: Dad, Mum, Brenda (my big sister), me, aged seven, and a big, friendly, nondescript dog, called Bob, I think.

There was no TV in those austere days, and the cinema reigned supreme. The RN ran a good one down in the dockyard area, so most Saturday nights we trooped down there, leaving Bob to guard the house (there were burglars about). This went well until we acquired a second dog, in the usual way of service families, from some friends who had been posted back to the UK and wanted a good home for a well-loved pet. This one was a chihuahua! "Looks like a rat", Dad said, but Mum liked him. He and Bob seemed to get on OK, despite the great difference in their sizes, and they played constant, boisterous games of hide and seek and chase together around the house and garden. The odd bit of furniture got knocked awry, but there was no real harm done.

One Saturday night we got back to the house from the cinema. It was eerily quiet. Furniture had been overturned, things were smashed and curtains had been pulled down. Worse still, there were splashes of blood all around the lightly painted walls. "Burglars," said Dad, and he reached for his prison warder's-issue truncheon, "but where are those dogs?" Then we heard pitiful whining. Bob, the big dog, was pawing at the bathroom door. One of his ears was gashed and dripping lots of blood. We hunted inside the bathroom and found that the chihuahua had jumped inside the toilet bowl for refuge; only his nose poked over the seat and he was scrabbling to get out again. After several big cups of tea and more pipes of "baccy", Dad deduced that the dogs had played together while we were out, but then the little one had nipped the big one's ear, probably by accident. He had not seen it that way, though (and any animal's ear bleeds very readily), and had chased the little 'un all around the place in true Tom-and-Jerry style until the toilet bowl had beckoned as a refuge.

A week or so later, with approval from on high, Dad had a gang of German prisoners, who were mysteriously kept in custody in Malta for years after the war was over, in to repaint the house. They – the Germans – turned out to be really nice fellows. After a few days, they were showing Mum pictures of their families back home, she was making them tea and egg and chips, and they were carving excellent wooden toys for us children. And the house was painted really well. I hope they all eventually got home OK after we had left Malta in 1949.'

Chris Fussell (b.1939).

PERSONAL STORY: LEISURE TIME IN LIBYA

Although his father was a civilian, Mick Kiernan effectively became an army child when his family lived in Benghazi, in Libya, between 1951 and 1955. Here, he recalls how he spent his leisure time there between the ages of twelve and sixteen. (To read about Mick's stopover in Malta in 1951, click here; and click here for some memories of his schooldays in Benghazi.)

'My father's employment as clerk of works meant that although a civilian, he was entitled to use the facilities of the Warrant Officers' and Sergeants' Mess located in Berka, and most Sundays would find us there. I was allowed to play darts and have a drink in the bar, followed by lunch in the dining room. At that time, Dad had a motorbike and sidecar, and we usually drove home with my mother in the sidecar, me on the pillion and Dad in exuberant mood.

In the extremely hot summer, we only had lessons from 8 am until 1 pm. For some reason, we had Wednesday afternoons free in the winter, and most of us headed to the cinema run by the AKC [Army Kinema Corporation] to watch the weekly film. Before we went in, there would be Arab boys in the street selling us peanuts, chewing gum, sweets etc from the large wicker bowls that they carried balanced on their heads. From 1953, at least three evenings of the week would find us at the AKC cinema, where the films changed four times every seven days.

By the winter months of 1953, we were spending most weekends and Wednesday afternoons at the sailing club in Benghazi harbour. It was a perfect winter playground: there were many upturned sailing boats on land for cleaning and refitting for the next year's racing season, and they made ideal hiding places when we were playing hide and seek.

The club had two separate buildings, each comprising a bar/lounge, locker rooms and so on. One was for officers and their families, and one, for other ranks [ORs], warrant officers and below. At that time my father had OR status, and our clubhouse was nearest to the sea overlooking the harbour. Beside the clubhouse there was a basketball area, which had a very smooth surface that was ideally suited to roller-skating. We made our own sticks and pucks and played our version of ice hockey – there were many bruised shins.

In 1954, most afternoons would find me at the sailing club with friends, where we spent a good deal of time in the swimming pool. The pool was formed with pontoons anchored in the sea to make three sides of a rectangle, the fourth side being the concrete hard surface, where steps and diving boards were sited. We had our own water-polo ball and practised throwing and swimming for long sessions in the late afternoons, when we had the pool to ourselves.

When the cricket season was on, we took the game very seriously. I was a fast bowler, and in common with the other bowlers, I had my own cricket ball. Waiting for the TCVs [troop-carrying vehicles] to take us to school in the early morning, we practised throwing and catching. One morning, the truck pulled in and the soldier on duty as conductor jumped down and shouted "Over here" to the lad who had the ball in his hand. The ball was lobbed high in the air to the soldier, who placed himself directly below it and, as it dropped towards the ground, he headed it. He fell to his knees and we rushed over to him as a huge bruise came up on his forehead as though by magic. To this day I can picture the scene as, for a split second, we all froze, realising what he was about to do.

We had a lucky escape in 1954 when a crowd of us, about ten boys and girls, hired bikes and took packed lunches for a day at Long Beach, a mile or so beyond the town's outer limits. Upon arrival, we dropped the bikes amongst the sand dunes at the back of the beach, stripped down to swimming costumes and headed, en masse, to the sea, where we spent a long time swimming and playing in the breakers. When we eventually decided to leave the water, it was to discover that we had been carried about 100 yards or so along the coast, to a point where the dunes reached down almost to the water's edge. We plodded up and down the grass-topped sand hills for about 30 yards before arriving at the hard-packed salt flats, where we encountered a rusting barbed-wire fence. Once through the fence, we were able to see signs hanging at intervals on the wire. They showed a skull and crossbones, below which were painted the German words "ACHTUNG MINEN" ["CAUTION, MINES"]. We had walked through a minefield! I don't know if it had been cleared, but it certainly gave us something to talk about!'

Mick Kiernan (b.1939).

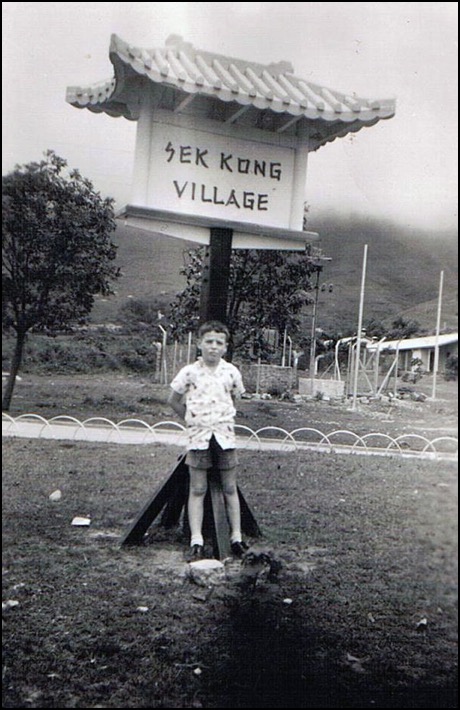

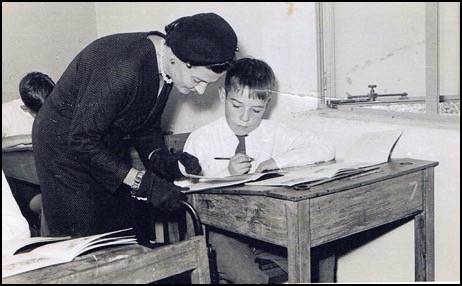

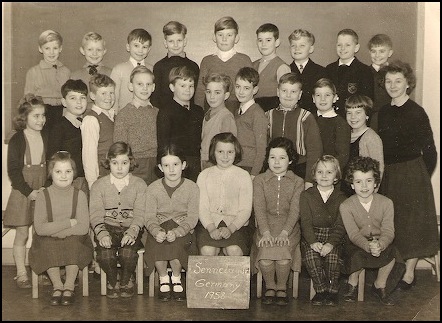

PERSONAL STORY: ‘THERE WERE NONE OF THOSE RAINY, FOGGY DAYS OF THE UK. GOOD TIMES’

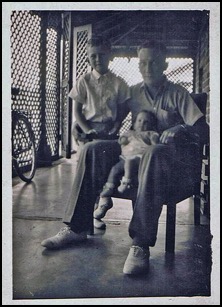

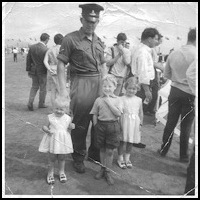

Following his birth in Cumberland in the middle of World War II, it would be over five years before Donald Bridge would meet his father, who was serving in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. Donald, who has kindly contributed his childhood photographs to TACA, tells the story of his life as an army child thereafter in a ‘travelogue’ that takes in postings to England, India, (West) Germany, the [Suez] Canal Zone and Cyprus. Click here to read an account of his schooling (‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘MY SCHOOLING AT ARMY SCHOOLS WAS ON A PAR WITH, IF NOT BETTER THAN, AT THOSE NON-ARMY SCHOOLS THAT I ATTENDED’), while one of his cache of photographs (of a Sunday-school teacher in Bad Oeynhausen, (West) Germany) also appears on TACA’s ‘SCHOOLING’ page.

‘I was born in Carlisle, Cumberland, in 1941. My mother was, at that time, living at 16 Annan Road, Gretna, but my father was away at war at my birth. My father, Thomas Donald Bridge, was a professional soldier in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) and, at the time of my birth, was a staff sergeant. He had joined the RAOC at Hilsea Barracks, Portsmouth, on 26 July 1935. Although born in London, he had gone to India as a baby. His brother Harry, two years older, had been born in India at Allahabad, and was also a professional soldier all his life with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME). Their father, Harry H Bridge, was in the Indian Army Ordinance Corps (IAOC), retiring in 1932 to 32 Queens Road, Walthamstow, E17. My grandfather was an Air Raid Precautions (ARP) warden early in World War II before being recalled to the Indian Army, then serving at the India Office until retiring again in 1948 and being awarded the MBE for his services to India. Upon his retirement, he moved to 20 Fairfield Gardens, Portslade, Brighton, Sussex, and this house was left to my father on the death of my grandfather. My mother, Maud Marion (née Courtman), lived at 9 Knotts Green Road, Leyton, E10, and met my father at Walthamstow tennis club. Both were very good tennis players, my mother slightly the better. They were married in September 1939.

In January 1940, my father was sent to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, and, after the fall of France, came out via St-Nazaire on 26 June 1940. He was posted to Longtown ordnance depot, near Carlisle, and my mother joined him there, living in lodgings in Gretna. My father was posted to the Middle East Land Forces (MELF), and was serving in that theatre of the war, in North Africa, Egypt and Palestine, from 14 November 1940 until 29 February 1944. He was at the first siege of Tobruk. Because he was fluent in Hindi, he was transferred to the IAOC on 5 March 1942 and served the rest of the war with Indian troops. On 1 March 1944, he was transferred to India. My mother stayed on at Gretna until my birth owing to the bombing in London (Leyton was on the bombing path for German aeroplanes), and was joined by her mother, Alice Courtman, shortly before my birth, all of us returning to 9 Knotts Green Road when I was about three months old, where we lived until about September 1946.

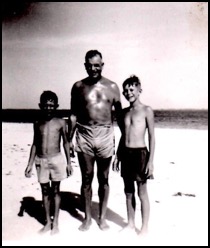

Above: Pictured in Kirkee, India, in late 1947: my father, Sub-Conductor T D Bridge, RAOC; me, aged six; and my sister, Sheila, who was then only a few months old.

THE 1950S AND 1960S: POSTINGS TO (WEST) GERMANY, THE CANAL ZONE, CYPRUS AND ENGLAND

On 24 April 1950, my father was posted to headquarters, British Army on the Rhine [BAOR], and we all moved to Bad Oeynhausen, staying at 28 Stein Strasse. Whilst in (West) Germany, we went twice on holiday to British forces summer-leave centres at Norderney (one of the East Frisian Islands) and Scharbeutz (on the Baltic, near Lübeck) and once to a winter resort at Ehrwald, in Austria, near Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Below: The NAAFI at Bad Oeynhausen.

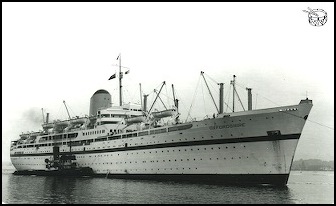

We left Germany on 20 August 1953, when my father was posted back to England for onward deployment to the Middle East Land Forces at Moascar, Ismailia, Egypt. We went to stay at Westbourne Transit Camp near Emsworth, Hampshire, to await a passage to the [Suez] Canal Zone. My father went to Egypt on 6 October 1953, and we then followed him, leaving Southampton on the troopship Empire Ken in early 1954, and arriving at Port Said via Algiers on 26 January 1954.

Below: 9 Gallipoli Road, one of our homes in Moascar.

Below: The NAAFI, on Moascar’s main road.

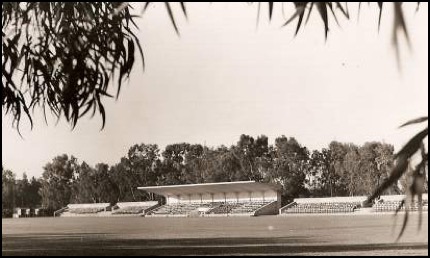

Below: Moascar garrison’s sports field.

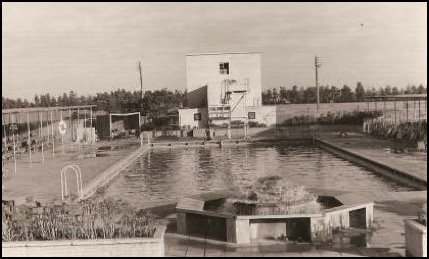

Below: The garrison swimming pool in Moascar.

In Moascar, we stayed in two houses, the last being 9 Gallipoli Road, until 20 October 1955. We went on holiday to the Sea View Holiday Camp at Port Fuad.

Above: My mother outside the entrance to Sea View Holiday Camp, at Port Fuad, in 1955.

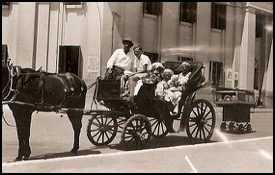

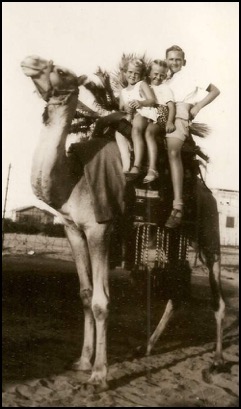

Left: Me and my sisters, Sheila and Barbara, on a camel at Sea View Holiday Camp, in August 1954.

Below: The Bridge family at Lake Timsah in 1955, with the Anzac war memorial in the distance.

With the running-down of the forces in the Canal Zone and the closure of the British bases in Egypt, my father was transferred to headquarters at Fayid, on the Great Bitter Lake, and then immediately to Episkopi, in Cyprus. We left Fayid by aeroplane (it was my first air journey) for Nicosia, arriving on 20 October 1955. In Cyprus, we lived in a hastily constructed village of pre-fabricated houses at 11 Jacaranda Drive, Berengaria Village, Limassol.

Below: 11 Jacaranda Drive (left), our married quarter in Berengaria Village (right).

We arrived in Cyprus just as the independence movement, enosis, and its terrorist arm, EOKA, was getting into full gear, and my father had to go to and from work at Episkopi in an armed convoy. Berengaria Village was surrounded by barbed wire, but we were used to this because so were Bad Oeynhausen and Moascar. However, I did not like Berengaria Village. As a growing teenager, I felt restricted after the life in Moascar (school until 13:00 hours, then the afternoon spent at French Beach, at the northern end of Lake Timsah, swimming and watching the ships pass up the Suez Canal) and became rebellious. Also, the threat to teenage English boys from EOKA was quite real: you could be shot, for a fifteen-year-old schoolboy looked rather like a seventeen-year-old national serviceman. So my parents decided that I should go to England to start a career, and I was asked what my choice would be. After watching the ships on the Suez Canal, my answer was the merchant navy, so on 24 August 1956 I left Famagusta on the troopship Dunera for Southampton, arriving there on 3 September 1956. The Dunera was returning empty to England, having brought troops out for the 1956 Suez landings. I was sent to the training ship HMS Worcester, off Greenhithe, in Kent, spending two years there until July 1958, when I was apprenticed to the Ellerman & Bucknall SS Company, with which I spent eight years at sea. My time at sea was spent travelling to the Persian Gulf, India, Ceylon [Sri Lanka], Pakistan, Malaya [Malaysia], Hong Kong, the Philippines, Japan, Australia, South Africa, South-West Africa [Namibia], Angola, the Congo, the USA and Canada, (West) Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France.

In the meantime, the family left Cyprus on 18 March 1957, when my father was posted to the ordnance depot at Bicester, in Oxfordshire, and they moved into married quarters at 6 Ernicot Close, Ambrosden. They stayed there until some time in 1961, when my father, by now having been commissioned, was transferred to the base ordnance depot at Viersen (near Rheindahlen), in (West) Germany. We lived at first at 35 Hugo Eckener Strasse, in Mönchengladbach, and then moved into one of a group of seven newly-built married quarters amongst the German population in Viersen. During this time, I was at sea either with Ellerman Lines or at college in London.

In mid-1965, my father was posted back to Bicester, and the family returned to Ambrosden, where we lived at 1 Quinton Avenue until 1971, when my father retired from the army with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. By that time, I had emigrated to South Africa and was living in Cape Town. My sister Sheila had married a soldier (who later worked as a civilian at the Bicester ordnance depot) and was living in Bicester; my other sister, Barbara, followed me to Cape Town in 1970. When my father retired, he bought a house in Launton Road, Bicester, and he and my mother lived there for about a year before coming out to Cape Town for a six-month holiday in 1972 and staying for four years. They sold the Launton Road house to Sheila and her husband, Eddie, and when they returned in 1976, they went to live in Portslade in the house that my grandfather had left to my father on his death in 1973. My mother died in Portslade in 1983, and my father, in Brighton in 1984, and there is a memorial to them in the gardens at Wakehurst Place in Sussex. Sister Sheila is still living in Bicester, and sister Barbara is living in Barrydale, near Swellendam, about 250 kilometres from Cape Town on the way to Johannesburg.

CONCLUSION

I agree with one of TACA’s contributors that returning to England from overseas was always something of a disappointment. England, especially during the 1940s and 1950s, seemed poor and somewhat backward in comparison to where we had been living in army bases overseas. All of the houses that we lived in in Germany had central heating, which was a rarity in England after the war. I also remember the crisp, clear winters in Germany, especially in Viersen, where it snowed in November, the snow then staying on the ground for the next three or four months, with blue skies overhead on most days. There were none of those rainy, foggy days of the UK. Good times. I loved it. All my mother wanted was a home of her own without moving, though, and she ended up at 20 Fairfield Gardens, Portslade, Brighton, which she disliked, and died there. I ended up in Cape Town. I couldn’t settle in the UK after all of the travelling. I hope that I haven’t bored you with this travelogue.’

Donald Bridge (b.1941).

PERSONAL STORY: MEMORIES OF AN ARMY CHILDHOOD

Roger Hall has already made guest appearances through his brother on TACA, in Richard Hall’s contributions to the archive (‘PERSONAL STORY: HAPPY DAYS IN HONG KONG, 1953’ and ‘PERSONAL STORY: MEMORIES OF MÜNSTER, 1958–60’). So it is fascinating to have the opportunity to read Roger’s wonderfully detailed side of the story, which begins in Woolwich, during the 1940s, and continues, following a long sea journey, in Hong Kong during the early 1950s, before moving on to England and (West) Germany.

‘My earliest memories of being an “army brat” date from the late 1940s, when I was living with my mother and father in married quarters in Woolwich, south-east London, which was then the headquarters and depot of the Royal Artillery. My father was a staff sergeant who had joined a Royal Engineers Territorial Army unit in 1938. At that time, the unit to which he belonged was a searchlight detachment working in conjunction with the anti-aircraft guns of the Royal Artillery. The two elements were then merged, and so my father became a gunner. He served in North Africa and Italy and was mentioned in despatches.

I was born in 1943, but did not see my father until I was two years old. I was told later that I was distinctly hostile to him. He returned to Italy after the German surrender and finally came back to the UK in 1947 and left the army. He was not happy in civvy street, however, and rejoined the army and was posted to Woolwich. The quarter that we lived in was in one of two Victorian tenement blocks, one called East Block, and the other, Old Block. The accommodation was very basic, had stone staircases with iron railings, and was very cold in winter. I recall huddling around an open fire trying to keep warm during a particularly cold winter (probably 1947).

London at that time suffered from smog during the winter months, and I recall walking to and from my first primary school, just off the Plumstead Road, in those conditions. Occasionally, the journey was taken by tram before they were withdrawn in 1952. I can still hear the distinctive clang and rattle that they made. At lunchtime, we were walked to an annexe down the road for school dinner, where the prevailing smell was of boiled cabbage. Woolwich was a place full of military history, and I recall captured artillery pieces displayed at the edge of the parade ground in front of the main barracks. There was also the Rotunda artillery museum containing many historic pieces of artillery. Visits to the barracks were not uncommon, and I can recall the 25-pounder guns lined up for inspection. They were towed by a Morris “Quad” vehicle, with an ammunition limber attached between gun and tractor. My father had become a quartermaster, and I was treated to visits to the stores and armoury, where I was offered “tea and wads” (buns).

My father worked with a civilian transport contractor known as “Pop” Barnes, and during the school holidays I travelled in the cab of one his lorries all the way to Isleworth, which, to me, seemed like the other side of the world. Another Woolwich attraction was the free ferry across the Thames. It was fascinating to watch the great cranks of the engine working from a viewing platform on the passenger deck. Sunday walks were taken across Woolwich Common, passing the former Royal Military Academy and the Herbert Hospital, which, I believe, was a military hospital. My brother was born in 1948, and coincidentally, or not, his first two initials are R A. Furthermore, he was christened in the Royal Artillery chapel.

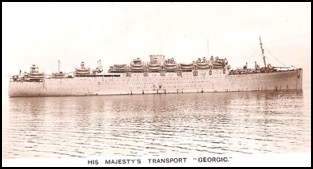

In early 1952, my father was posted to Hong Kong. He travelled on the troopship MS Dunera. The three remaining members of the family remained in the UK, with a promise that we would follow in due course. We then moved into an army-requisitioned semi-detached house in Welling, Kent. I attended Little Danson Primary School, which I enjoyed. After nearly a year of separation, my mother – who had tired of waiting for news of our travel arrangements – took my brother and me to the War Office in Whitehall and made it plain that she would not leave until she was told when we would leave for Hong Kong. It did the trick, because some six weeks later we boarded the troopship HMT Empire Orwell at Southampton for a twenty-eight-day voyage to the Far East. Before I left my primary school, I was presented with a pop-up cowboy book, to wish me bon voyage, which had been bought with contributions from the whole class. The money was collected while the teacher, Mr Rush, sent me out of the classroom on spurious trips to measure the distances from the various school buildings to the oak tree in the middle of the playground! It was not every day that someone left for Hong Kong. I still have the book.

SAILING TO HONG KONG

We sailed in December 1952, and made our way down channel and into a very rough Bay of Biscay. We passed Gibraltar, and continued into a relatively calm Mediterranean. The first port of call was Port Said, but we were not allowed ashore due to civil unrest and anti-British rioting. However, this did not prevent Egyptian entertainers, called “gully gully men”, from coming on board. They were conjurers and illusionists, which I had never seen before. The ship was also besieged by “bumboats” on the seaward side of the dock, holding floating vendors selling Egyptian souvenirs. They held up items for sale and there followed the ancient art of haggling and bargaining for the best price. When a deal was concluded, the seller threw up a basket on a rope into which you placed the agreed sum and then wound it back down, all the time hoping that he would honour his part of the deal. I still have the leather purse I that bought that day.

We then proceeded into the Suez Canal, which was where we experienced the heat of the tropics for the first time. The desert was stretched out on either side of us, as far as the eye could see. At one point, I recall an old steam train running parallel to the canal, with locals sitting on every available space on the roof of the carriages. Next came the Red Sea, a much broader expanse of water, which, I thought, really did have a red colouration. The next stop was Aden, which was even hotter, and here we were allowed ashore. My mother had made friends with a navy wife and her son, who shared her cabin, and who were travelling to Singapore. I shared a cabin with two other boys. We were down on “F” deck, right down near the waterline. When it was rough, you could see the sea swirling past the porthole. One very hot night, with the porthole open, I was awoken suddenly to find myself soaked from head to foot. A storm had blown up, and sea water was coming in through the porthole. I trudged around to my mother’s cabin in my bedraggled state to dry off and get some dry pyjamas.

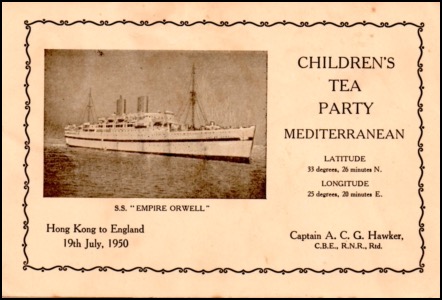

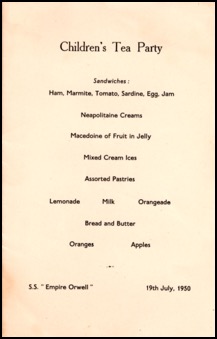

On our arrival in Aden, the two families took a taxi ride into the Crater district. The taxi driver sported a large, curved dagger in his waistband, and my mother later said that she thought that we were all going to be murdered by him! As we left Aden, an Arab dhow collided with the bow of our ship, snapping off its bowsprit. I can still see the crew gesticulating and hurling abuse as we continued on our way. We then crossed the Bay of Bengal on our way to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and docked at Colombo. On the way, a children’s tea party was held, of which I have no recollection, but I do still have the menu. I shall always remember the warm, sweet aroma on the breeze as we neared the land. It seemed very inviting. We had a short tour of the island by bus, and called at the Mount Lavinia Hotel. Outside the hotel, a native boy asked if we would like a coconut. We said that we would, and he promptly shinned up a nearby tree and knocked one to the ground. An older man sliced the top off the coconut with his machete, and we all drank the coconut milk, something that I had never tasted before. We had some refreshments in the hotel where, also for the first time, I drank freshly squeezed orange juice from a glass, the rim of which had been dusted in sugar. I can still taste it today. Nectar! It should be remembered that we had not long left England, which was still in the grip of post-war rationing, so this was luxury beyond our wildest dreams.

I recall that the children on board ship were given some rudimentary lessons, but that these did not take up the whole day. The one class comprised all ages. It was more of a token effort, which no one took very seriously. There was a small ship’s cinema, which had regular cartoon shows, which usually took place in the afternoon. After leaving Colombo, we crossed the Indian Ocean and sailed on down through the Straits of Malacca, with Sumatra on our right and Malaya [Malaysia] on the left. Our next port of call was Singapore, which seemed even more exotic. This was our first taste of the Orient proper. We toured the city, calling at “Change Alley”, the famous market, where souvenirs were bought. I was conscious of the different races living and working cheek by jowl: there were Indians, Malays, Pakistanis and Malay Chinese. There was also a large British naval and military presence. We left Singapore on the last leg of our journey up the South China Sea. This was very rough, and my mother suffered from severe seasickness, alleviated by something prepared by the ship’s barman, which, I believe, included champagne and brandy.

OUR ARRIVAL IN HONG KONG

Our arrival in Hong Kong Harbour is also something that I shall never forget. We docked in Kowloon, almost adjacent to the Star Ferry terminal, which was overlooked by Hong Kong Island and the towering Peak. The harbour was full of ships from all over the world, interlaced with large sailing junks and small sampans. The whole place had an energetic bustle. My father met us off the ship, but because we had jumped the gun, no married quarter was available. (As far as I recall, quarters were allocated on a points’ system based on the length of separation.) So we moved into temporary accommodation in Austin Apartments in Austin Road, Kowloon, just off the main shopping thoroughfare of Nathan Road. Our apartment looked out over a cricket pitch – very English! One balmy evening, we watched, from our balcony, a floodlit military tattoo on the pitch, which included pipes and drums with marching and countermarching.

We did not stay in the Austin Road apartment for very long, however, then moving into a two-bedroom first-floor flat at 132 Boundary Street in Kowloon Tong. There was a balcony on two sides of the flat, which faced north, looking towards Lion Rock. It was directly under the flight path for Kai Tak Airport, which was no hardship as flights were fairly infrequent. I seem to recall that there was only one BOAC [British Overseas Airways Corporation] flight a week from England, which took four days to get there. The approach to Kai Tak has passed into legend as one the best white-knuckle rides outside of an amusement park. Aircraft flew in parallel to Lion Rock, down to 500 feet, and then turned sharp right to land on a single runway that jutted out into Hong Kong Harbour.

EXPLORING HONG KONG

We soon set about exploring this exotic place. As any old China hand will tell you, Hong Kong was then an incredible mix of East and West. The main shopping street in Kowloon was Nathan Road, which ran due north from the Peninsular Hotel, more commonly known as “The Pen”. In those days, it was the most luxurious and exclusive hotel in the colony. The shops in Nathan Road were an eclectic mix of Chinese and European, selling everything from fake Japanese copies of cameras to Indian silks and everything in between. I recall a pastry shop selling what I assumed were French bread and cakes, where you could buy freshly baked bread until 10 o’clock at night. It was called Chanticler. There was an English-sounding chain of grocers’ shops called Lane Crawford, which was just like a branch of Sainsbury’s in an Eastern setting. All the classic English staples could be bought there, including Marmite, Weetabix, McVitie’s biscuits & Tate & Lyle golden syrup. I also recall a café/restaurant chain called Dairy Farm, where the locally bottled orange drink, called Green Spot, was always a favourite. Its rival was Chocolate Soldier, a chocolate-flavoured milk drink that was always served ice cold. Every public place had ceiling-mounted three-bladed fans to try to keep the temperature at a reasonable level.

Yet you only needed to turn off down any one of the side streets to step right back into old China. There were vegetable stalls selling a whole range of items that I had never seen before. The Chinese bargained for everything at the tops of their voices, oblivious of those around them. One shop specialised in “hundred-year-old” eggs, which sounded quite unpleasant to me. The Chinese like to shop at least twice a day to ensure that the ingredients are fresh, and livestock, such as chickens, was sold live and throttled by the vendor as you completed the transaction. My mother was horrified when one such vendor rang the doorbell at our flat to offer a chicken from one of the rattan cages that he carried balanced on a bamboo pole, which he would have despatched there and then if she had said yes. She did, however, like shopping at Chinese vegetable stalls just off Nathan Road, and opened an account at one. The proprietor and his staff (his family?) were all very deferential, and nothing was too much trouble for them. My mother was not, however, a fan of the NAAFI shop, which was in Whitfield Barracks, where I went to school. (During the 1990s, the buildings that comprised the school became the Museum of Hong Kong.) I remember little of my schooling there, which took place in single-storey colonial buildings, with the inevitable ceiling fans constantly revolving to mitigate the heat. Air-conditioning would come later. I remember only one teacher: Mr McKinnon. I recall that we had no lessons in the afternoon during the summer, which enabled us to go to the beach.

My father’s battery was stationed above Silver Strand Beach, on the road to Clearwater Bay. The other two batteries were at Stanley Fort, on Hong Kong Island, and Stonecutters Island, in the harbour. The views from the camp were spectacular. To the north-east was the Sai Kung Peninsula, with numerous islands in between. To the south-west, looking over Junk Bay, was Hong Kong Island itself. The small, sandy beach was reached down a steep cliff path, and never seemed to be crowded. The journey to the beach was usually taken by single-decker bus, which we caught from just outside our flat. It was always filled with local Chinese people, many of whom carried livestock with them. We usually sat at the back of the bus, and, at a point about halfway to our destination, the bus would come to halt and the driver would walk down the length of the bus to offer my father a cigarette! We could only assume that we were regarded as honoured guests. The cigarette having been lit, the journey continued. The afternoon was then spent swimming, fishing and generally skylarking. It really was an idyllic existence. On certain afternoons, the battery would fire its 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns right over our heads at one of the adjacent islands, or at a drogue towed by a small aircraft. This resulted in a harvest of stunned fish floating on the surface of the sea. At approximately 4 pm, the sergeants-mess waiter, who was nicknamed “Chicko”, would descend to the beach bearing a large tray with four cups and saucers and a large pot of tea, which was taken laced with lots of tinned Carnation milk – ugh! Later on, we abandoned the bus and instead used a brand-new Hillman Minx taxi, which had just arrived in the colony. The taxi rank was right beside the nullah (storm drain), which could smell pretty unpleasant during hot, dry spells.

I recall journeys to school in the back of an army 3-ton Bedford lorry, complete with an armed soldier. At weekends, we explored further afield, with trips to the other two batteries at Stanley Fort and Stonecutters Island. One visit to Stanley was to attend the children’s Christmas party. To get to Stonecutters Island, we travelled by small landing craft and simply ran down the ramp on arrival. On several occasions, we ventured up into the area known as the New Territories, north of Lion Rock up to the border with Red China. This was a totally rural area and looked much as China must have done for thousands of years. Small villages were surrounded by paddy fields ploughed by water buffalo. There was a beautiful inlet at a place called Shatin, where there were four tides a day. We usually travelled by train from the station beside the Star Ferry in Tsim Sha Tsui. The trains were hauled by large steam engines, which I assumed were American because they had a cowcatcher and a large headlamp on the front. The local women all dressed in black and wore circular coolie hats to protect them from the sun. Even further afield was Tai Po market, where the only sign of Western influence was the inevitable red Coca-Cola fridge. It was at Tai Po that we bought a pet rabbit, which I assume that we gave away when we returned to the UK.

As well as the beaches on the mainland, we visited some on Hong Kong Island. These included Repulse Bay and Shek O. Repulse Bay was clearly an upmarket location, with a smart hotel at the back of the beach. Aberdeen, with its floating restaurants, was visited, too, although we never ate there. There was also a beach at Stanley Fort, on the south side of the island. There were numerous ferries shuttling back and forth to the outlying islands to the west, one of which we took to Lantau Island, on which can be found Silver Mine Bay. On the return trip, a Chinese family insisted on sharing their crab picnic with us, without a word of English being spoken.

One benefit of service life in Hong Kong was the provision of an amah, amahs being local girls, usually in their late teens or early twenties, who worked as housemaids/cooks to the family. I particularly recall one girl, called Ah Gee. She spoke rudimentary English, but my brother and I were always addressed as “Lodger and Lichard”. Mother treated her like one of the family, and she was obviously upset when we had to leave, and presented us with a farewell gift of Chinese crockery and chopsticks. They are still in my possession.

The local Anglican church in Kowloon had a Scout troop and Scout pack, and I duly joined the 12th Kowloon (Christchurch) Pack. It was a league of nations, including as it did several boys from different European countries, as well as Chinese boys and other Asians. The annual camp was set to take place up in the New Territories under canvas, and I was really looking forward to what sounded like great fun. We were told to meet at Kowloon station to catch the train up to Shatin. I was proudly sporting my newly purchased rucksack when my father took me to the station, but as we stood waiting, we began to realise that something was not right, for there were no other Cubs or Scouts to be seen. Eventually, we returned home, and found out that the camp had been cancelled as the campsite had been washed away by the monsoon rains; I was the only Cub not to be told beforehand. I have never forgiven the Scout movement! Two other trips organised by the Scouts were, firstly, to the Coca-Cola bottling plant on the island, where we were allowed to drink as much Coke as we wanted, which started a lifelong addiction to that drink. Secondly, we visited Kai Tak Airport, where we were shown over a Boeing Stratocruiser and were each presented with a bag of airline goodies.

THE VOYAGE BACK TO THE UK

In late 1953, we started our return voyage to the UK, coincidentally also on the Empire Orwell (below). During our time in Hong Kong, we had seen other troopships come and go, amongst which I recall the Dunera, the HMT Asturias, the HMT Empire Windrush (which was later to catch fire and sink in the Med on her way back to the UK) and the HMT Empire Fowey. On the way home, we encountered rough seas in the Med and the Bay of Biscay. My mother suffered severe sickness, which could only be alleviated by the brandy-and-champagne concoction mentioned before! As far as I recall, neither I nor my brother suffered any ill effects, but it did make it very difficult to make your way around the ship. Meal times were also very eventful, with crockery sliding all over the tables every time that the ship took another plunge. Each table had a small, raised surround, which prevented anything ending up on the deck. We had a children’s Christmas party in the Bay of Bengal, the menu for which is still in my possession.

As well as the families on board, there were also soldiers of various units returning from Korea, the war having just finished there. One group that we became friendly with was from the 5th Dragoon Guards, who gave us their unwanted Korean and Japanese banknotes, which I still have. (I realise now that many of them were young national servicemen who had just endured a very unpleasant experience.) On one of the calmer days, a flying fish suddenly flopped on to the deck, and was promptly pinned to a piece of wood as an exhibit, with its “wings” spread out for us kids to examine. As we passed Gibraltar, I took a picture of the Rock and promptly dropped my plastic-bodied Brownie 127 on the deck, cracking the case and letting in the light.

I recall us making our way up Southampton Water, and, as we did so, we were shown the abandoned hulls of the Princess flying boats that had been cocooned at Calshot, Hampshire, pending a decision on their future. They were designed to be the future of post-war British civil aviation, but never flew again and were subsequently broken up. Just before we docked, we passed under the stern of one of the Cunard “Queens”. It seemed enormous compared to the Orwell. On our way through London, we stayed at the Union Jack Club beside Waterloo Station, which was a forces hostel providing subsidised accommodation for service people and their families. We then went to live in Hythe, on the Kent coast, in a high-class B & B, until we found our feet in the UK.

AN UNSETTLED STINT IN ENGLAND

My mother had decided that army life was not for her, and my father left the army for the second time since the war and took work as an assistant chimney sweep! The man he worked for was a con artist who targeted wealthy homes in Folkestone, Kent, where he would set up his impressive electric cleaner, plug it in (after closing the door to exclude the owner) and then run the machine for about twenty minutes without going anywhere near the chimney, after which he would charge an exorbitant fee, receiving the grateful thanks of the owner as they left. This was a revelation to my father, who had never encountered anything like that in the army. Six months later, he signed on again and was promptly posted to Cheshire. Meanwhile, we took a tenancy in the basement flat of a converted Martello tower on the seafront. It was very cold, had walls 8 feet thick, and was quite different from married quarters, even if it was a former military building.

My education then started to take a few twists and turns. I had taken the forces equivalent of the Eleven Plus (the Moray House exams) in Hong Kong, and had failed. In Hythe, Kent, I was told that I had to attend the local primary school and take the Eleven Plus, which I promptly failed, and in September 1954, I started at Brockhill Secondary School. I recall an embarrassing incident when the form teacher thought that it would be interesting for the class if I gave a short talk on my Far East adventure. In those days, I was painfully shy, and regarded the whole episode as a nightmare. A married quarter became available in Cheshire, and my parents, in their wisdom, decided that it would be better for me to finish my first year of secondary education by staying in the south. So I went to live with a farming family and enjoyed being involved with farming life, even learning to drive a small caterpillar tractor.

I rejoined the family in the village of High Legh, about halfway between Warrington and Knutsford. The regiment, the 56th Heavy Anti Aircraft (HAA) Regiment, Royal Artillery (RA), was based around the former manor house and was set in beautiful grounds, with lakes and woods – a wonderful playground. It was a lovely part of England, and the people were very friendly. Bizarrely, I was told that I was too young to attend the local secondary school in Knutsford, and so spent a term in the village primary school, where I took the Eleven Plus for the second time and failed again! In September 1955, I started my first term at Knutsford. Had I remained in the south, I would have been starting the second year. I made a lot of friends, but was becoming conscious of being thought of as an oddity because of my family’s service background. One of my contemporaries, on being told that my father was a soldier, asked, “Does he kill people?”

My father’s regiment would go on exercise for several months between March and September, when the whole unit would decamp to a small village called Tonfanau, on the Welsh coast near Towyn. The guns engaged in target practice, firing at a drogue towed by an aircraft. My father was able to come home for the odd weekend, but this only gave my mother further cause for complaint. The married quarters were newly built and reasonably comfortable by the standards of the time. (There was no central heating, just an open fire in the sitting room and a coke-fuelled stove in the kitchen.) I recall shopping trips to Manchester that involved walking 2 miles to the next village, a bus ride to Altrincham and, finally, an electric train into the city. With apologies to Mancunians, I thought Manchester much inferior to London. We had three enjoyable years in Cheshire and at the end of 1957, my father asked us whether we would like to go to Cyprus or Germany. I cannot remember what our choice was, but, knowing the perversity that governed army decision-making, if we had plumped for one, then we would have been given the other. We were told that it was Germany, and in the time-honoured fashion, Father left us for his new posting in mid-1957, leaving us to return south pending the allocation of a married quarter in Germany. The family returned to Hythe, where we took a private tenancy in a bedsit. I resumed my education at Brockhill, where I found myself in the fourth year, having left Cheshire at the end of the second year!

THE MOVE TO MÜNSTER

At Christmas 1957, my father came back to the UK and told us that we would be joining him in Germany early in the new year. At the time, he was stationed in Detmold, but then moved on to Minden, and by the time we joined him, he had been transferred to Münster. (The army was being downsized, resulting in many regimental mergers.) In February 1958, my mother, brother and I made our way to Harwich to board a troopship, which I am reliably informed was the HMT Empire Parkeston. We sailed overnight and docked at the Hook of Holland the following morning. The military train then took us straight to Münster, where we were allocated a modern, centrally heated quarter on the outskirts of the city, but within walking distance of the barracks, which had served the same purpose under the Nazis. Münster was a large garrison town, with many different regiments stationed there. I recall the Royal Scots Greys (the Duke of Kent was serving with them at the time), the 4th Royal Tank Regiment and the Seaforth Highlanders. There was a large military hospital, together with all the other support units, including the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC). Near our quarters was another small estate occupied by RAF families, the men serving at RAF Gütersloh.

I was told that I would attend one of three boarding schools for service children, the nearest of which was Windsor School, Hamm. However, we were duly notified that I would be attending Prince Rupert School (PRS), in the northern seaport of Wilhelmshaven. (The third possibility was King Alfred School at Plön, up near the Danish border.) I was told that I would start at the beginning of the summer term in April 1958, and so I again had to attend a primary school for three months in a class with children many years my junior. We then moved to a larger quarter around the corner, where we remained during our three-year posting. This was a luxury home compared to anything that we had experienced in the UK: we had full central heating, double-glazing and all mod cons.

My brother and I liked Germany. From day one, we were instructed to respond to Germans by saying Nicht verstehen – Engländer [“Don’t understand – English people”] (in perfect German). To explore Münster, we took the local municipal bus and, again, had been told to ask for Einbahnstrasse (“one-way street”), which clearly confused the conductor, and we soon realised that we should have asked for Eisenbahnstrasse (“Railway Street”)! We did gradually pick up rudimentary German, and were able to get by in the local shops. My mother was not impressed with the NAAFI shop, and preferred to shop for fresh vegetables in the market place beside the cathedral. Some service families made no effort to meet locals and never strayed from the NAAFI to try local shops, where Lebensmittel (“food”) was invariably cheaper. Regulations were still in force that advised against purchasing local milk. We ignored this stricture in taking our litre container to the dairy down the road, and never suffered any ill effects.

My parents got to know a German family whose daughter was employed as a nurse at the barracks. During the 1930s, she had been a member of the Hitlermädchen (the female equivalent of the Hitler Youth). She told us of her experiences working as a labourer on autobahn construction. She described the great optimism and pride that was felt by most Germans at that time.

Although we did not fully appreciate it at the time, Münster had been extensively bombed by both the RAF and the USAAF during the war, and yet it was clearly a prosperous, modern city whose medieval centre, including the old streets, the Rathaus [town hall] and the cathedral, had been rebuilt. This was the beginning of the post-war economic miracle, or, as it was known in German, the Wirtschaftswunder. There were a number of attractive places to visit in the surrounding countryside, including the village of Tecklenburg, high up in the Teutoburger Wald [Teutoburg Forest]. We often used to visit the Möhne-Damm [Möhne Dam], which was about an hour’s drive away. The village inns were great places in which to eat out, and there I developed a lifelong love of Wiener schnitzel and bratwurst. There were Canadian forces stationed in the towns of Werl and Soest, where we had access to the shop of the Maple Leaf services, which was the Canadian equivalent of the NAAFI, and which introduced us to a whole new range of goods and foods from North America, including the then unheard of maple syrup – lovely!

PRS, TWA, AND MY LATER LIFE

The prospect of going away to boarding school for the first time was quite a daunting one. Prince Rupert School would be the tenth and final school that I had attended since my education started! My mother spotted another boy living in an adjacent married quarter and asked him to keep an eye on me as I travelled north to Wilhelmshaven. I shall never forget the sight of the school train as it pulled into Münster station: it was like a scene out of one of the early St Trinian’s films, with kids hanging out of the carriage windows, waving their blue-and-white scarves and shouting to their friends to join them. The train was one of two laid on specially for the pupils of PRS, starting their journeys in Cologne [Köln] and picking up pupils from the major garrison towns as they headed north. For me, it was the beginning of a wonderful experience that I shall never forget. On the first night, I was homesick, but from then on, I loved it. I did, however, find myself back in the third year, having left my school in Kent in the fourth year.

Many ex-PRS pupils belong to The Wilhelmshaven Association (TWA), which holds biennial reunions at various UK venues. The school at Wilhelmshaven was closed in 1972 and moved to Rinteln, where it remains to this day. However, with the continued withdrawal of our forces from Germany, its future must be in doubt. For a detailed insight into what life was like at PRS between 1947 and 1972, I recommend reading a book compiled from reminiscences of former pupils and staff published by The Wilhelmshaven Association in 2004. Space does not permit me to recall all of my personal experiences there, but suffice to say that PRS was a school ahead of its time, being a comprehensive, co-educational boarding school. All of the pupils had one thing in common: they were all “service brats”. It was the first time in my school life when I felt at home, and not the odd one out: we had all experienced the disruption and uncertainty that service life brings to a military child. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world!

We returned to the UK in late 1960, and my father retired from the army in the spring of the following year. I did briefly consider joining the army because I knew that my father had enjoyed service life, but decided against it. Despite my disrupted education, I was able to make a career in the legal profession, and retired after almost forty years in 2002.’

Roger Hall (b.1943).

PERSONAL STORY: SOME SNAPSHOTS OF GROWING UP IN POST-WAR AUSTRIA AND BERLIN

Lorina Lumsden's father, a staff sergeant in the Intelligence Corps, was posted to Austria in 1948, and his family followed him there in 1949. They returned to the UK in 1952 before being posted to Berlin, in (West) Germany, from 1953 until 1957. Lorina recalls these postings below.

'My maiden name was Lorina Federl, and I had two brothers, Michael and Richard, and four sisters, Elizabeth, Mary, Georgina and my baby sister at that time (she was born in Austria), called Kathleen. In Austria, I went to school in Graz, and many of my siblings went to Klagenfurt School.

Below: A photograph of forces children taken at a birthday party in Austria in about 1951. Lorina writes: 'I am second from the left at the front; my brother Michael is on the far right at the front, and my brother Richard is standing to the left of the girl at the back who is wearing a strange-looking party hat.'

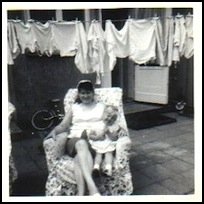

Below: The Federl family. Lorina, then about nine or ten years old, is sitting alongside her mother and their dog.

In Berlin, my school was in Hertha Straße in Grunewald. The property had belonged to a famous German musician. I went to school with my brother Michael and sisters Georgina and Kathleen. We lived in a lovely apartment in Charlottenburg. My brother and I were in the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, and we assembled at a barracks that overlooked Spandau Prison, where Rudolf Hess was being held.'

Lorina Lumsden (née Federl, b.1943).

PERSONAL STORY: THE ARMY LIFE

Winifred Hamilton’s father, Thomas Lang Hamilton, served with the Royal Signals and was also seconded to the Malayan Army, which meant that Winifred and her family consequently lived in Scotland, Egypt and Malaya (Malaysia) during the 1940s and 1950s, as Winifred relates here. Winifred adds: ‘Looking back, I wouldn’t change my experiences for anything’.

‘I was born in Scotland in 1944. In the late 1940s, we joined my father, who was in the Royal Signals, in Egypt. First, we had to travel to London, and then to Harwich and the Hook of Holland, followed by a train to Trieste and a ship to Port Said. We lived in Ismailia for about two years, first in the downtown area, and then, after I contracted dysentery, moving into Moascar Garrison. We lived in three different houses: one, a block of apartments, then a tent-top building near the airfield, and finally another house for a very short time. I went to school in the garrison and also remember going to the cinema just outside the gates. We often went on my father's motorbike to Port Said, with my mother on the pillion behind and me in front, sitting on the tank!

We were evacuated to Scotland because of an emergency, in October 1951, I think it was – certainly before the king died [George VI died in February 1952]. It was very traumatic: we were all told to pack up, having been given only a day or so’s notice that we were being shipped back to Britain. Back in Scotland, I lived in barracks in Glencorse, just outside Edinburgh, and then in Dreghorn Barracks, near Colinton.

When my father was seconded to the Malayan Army, we joined him there in 1955, sailing out to Penang on the SS Canton (my sister had just been born by then). My father fought against the communist insurgents and was wounded several times. We stayed in Ipoh for a few months and then moved to Taiping, where I attended the army school. My father organised a motorcycle stunt team and performed many solo stunts, including jumping through a hoop of flames! I also remember a holiday taken in Singapore near Changi: we went down by train from Taiping, which was very exciting, but the holiday camp was a dump – just old Martello-type towers with bare light bulbs. I also remember the airport at Changi being very small and having a windsock – it's now the internationally acclaimed Changi Airport. I passed the Eleven Plus exam while out there, but we returned to Britain in 1956, which meant that I missed out on going to the boarding school in the Cameron Highlands [Slim School] and instead attended a Scottish academy.

I enjoyed the army life, but regretted having to leave friends and toys behind every time we moved. I also found that although I could keep up well with most subjects, arithmetic was always a problem because of the school changes. I think that I have been relatively successful, in spite of the fact that I had moved schools seven times by the time I was eleven! I was an academic teaching at university for forty-plus years, and have just recently retired.’

Winifred Hamilton (b.1944).

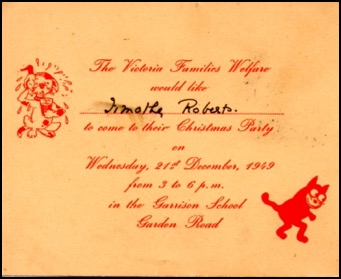

PERSONAL STORY: REMINISCENCES OF AN ARMY BRAT, 1946-65

Tim Roberts grew up after World War II as the son of 14522016 Warrant Officer II Frank Roberts, of the Royal Army Pay Corps (RAPC). In his detailed and evocative recollections of life as an army brat, he outlines the places where his father’s career took his family; the transportation that they used; the accommodation in which they lived; the domestic help that his family had while living abroad; his education; the extracurricular activities that he enjoyed; and such aspects of ‘mess life’ as children’s Christmas parties. Finally, he reflects on how growing up as an army child has affected him as an adult.

‘IN THE BEGINNING

My mother, Joan, was called up to the ATS [Auxiliary Territorial Service] in the middle of World War II and, after training in Pontefract, was assigned to the army pay office in Nottingham. There, she met my father, a corporal in the RAPC. They married when the war ended, and I was born in November 1946.

JOIN THE NAVY AND SEE THE WORLD – JOIN THE ARMY AND SMELL IT

Despite the well-known dictum [above], our family was generally fortunate with postings, although there was a hitch with the first one after I was born. Dad had been working at the War Office in London, and, in 1947, was promoted to sergeant and posted to Hong Kong via temporary assignments in India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). My mother could not get a passage to accompany him, and we had to wait until June 1948 to go out and join him.

The major part of my father’s duties in the colony was dealing with currency exchange for forces personnel moving in and out. Many a night he would sleep with a large bag of Hong Kong dollars under the bed and a revolver under his pillow. One incident he recalled was being summoned to Government House one morning and being sent upstairs to a guest room, where he was greeted by a suave-looking figure in a silk dressing gown for whom he exchanged some sterling. On leaving, Dad enquired who this person was, to be told it was Mr John Profumo, later Minister for War, who would become embroiled with Christine Keeler, Mandy Rice-Davies, Stephen Ward and a Russian naval attaché, in what became known as the “Profumo Affair”. Older readers will recall that the minister was forced to resign – of course, such a thing would be unlikely to happen these days!

At the end of this Far East tour, Dad returned to Nottingham Pay Office. Eighteen months later, he was made staff sergeant and posted to BAOR [British Army on the Rhine], based in Düsseldorf [West Germany]. There, his job included being visiting paymaster to several units in the area. He was assigned a car, an oval-windowed Beetle, and a driver, who was a Czech ex-PoW [prisoner of war] awaiting resettlement. From time to time, my brother, Martin, and I were able to accompany them on their travels around the Rhine district. In 1955, it was back to Nottingham for another three-year stint.

My father’s final overseas posting, and promotion to WO II, came in 1958, when he was sent to Command Pay Office Nairobi, Kenya. He returned to the UK in 1961, assigned to Officers’ Accounts at Rogers House, Ashton under Lyne. Here, he taught the arcane art of army accounting to new recruits – the last of the national service boys and civilian clerks. He had hoped to wangle a further posting overseas, and Bermuda was spoken of, but, ho hum, his Ashton posting was extended and he served out his days as quartermaster (regimental quartermaster sergeant, RQMS) in charge of supplies, maintenance etc until his discharge in 1968. During this final stint, he received his Long Service and Good Conduct Medal from the general officer commanding the district: it promptly fell off as the general stepped back!

GETTING THERE

Travelling to postings could be viewed as a hassle, or as an adventure and an education. There was certainly an advantage for me later, when it came to geography exams, having experienced the places and not seen them solely through the pages of a dusty textbook.

Above: Aboard the HMT Lancashire

in July 1948, en route to Hong Kong.

We returned from Hong Kong as a family, complete with my baby brother, in July 1950 on the HMT Empire Orwell. Life on board the troopship – which, incidentally, began its life as a German vessel – was fun for us children. There were no married cabins, and my father’s accommodation was with the troops. While the ship was in the tropics, many of the men opted to sleep out on the deck under the stars, and on some nights, I was allowed to join them. More entertainment was to be had in the mornings when the decks were swabbed, and I got a liberal hosing-down from the crew. My brother, who learned to walk during the six weeks of the journey, adopted the gait of a drunken sailor and had to relearn the skill once he was back on dry land.

Above and below: Children’s parties were held aboard the HMT Empire Orwell during the voyage from Hong Kong to England in 1950.

It would be another ten years before we had a family car, so travel back home in England was by public transport. Coupled with the fact that I had relatives who worked for the railways, travelling on the boat trains, in Britain and on the Continent, was probably what started my lifelong love of steam locomotives.

It wasn’t long before we were aboard a boat train again, this time bound for Harwich to connect with the Hook of Holland ferry. From there, it was on to the Blue Train and down the Rhine Valley to my father’s posting in Düsseldorf. Two memories come to mind from this journey: the beautiful springtime blossom in the Dutch and German countryside; and enjoying my first formal meal in a railway dining car. Eating soup on a fast-moving train was a particular challenge for a youngster, especially as its serving seemed to be timed to coincide with the crossing of many sets of points. During our three years in BAOR, we travelled home and back by this route annually when my Dad had leave. My mother’s parents also travelled out by this route to visit us one Christmas; it was my Nanna’s maiden overseas excursion and the first time that “Pop” had been out of the UK since being invalided home from Dar es Salaam during World War I. They were thrilled to be made guests of honour, seated at the garrison sergeant major’s table for the mess Christmas dinner, and, despite their protestations, were never allowed to pay for a drink throughout their holiday.

After our next spell in Nottingham, our move to East Africa [equivalent to modern Kenya] was made more exciting by giving us our first experience of flying. We flew out from Blackbushe Airport, on the Hampshire/Surrey border. The aircraft was an ancient Handley Page Hermes – belonging, I think, to RAF Transport Command – and we sat facing the rear. The route was via Rome, Benghazi (in Libya) and Wadi Halfa (in Sudan). Unfortunately, one of the plane’s engines failed at Benghazi, and we had to wait for twenty-four hours while spares were flown out and fitted. The combination of desert temperatures in the 100°Fs plus the serving of a foul-smelling soup, complete with fish heads, did little to improve the mood. However, the national-service boys soon found an old table-tennis table in the camp that was our temporary accommodation, and a twenty-four-hour tournament for all was quickly in progress. The routing via Wadi Halfa was because of repair work at Khartoum Airport. We landed in darkness, guided by petrol flares lining the approach and runway as there were no landing lights. It was a contrast to our final destination, Nairobi’s smart, new Embakasi Airport. During World War I, my grandfather had reached as far inland as Nairobi, which, at the time, was hardly more than a railhead, with a few corrugated huts.

My flying days continued when I was sent home to boarding school and returned for holidays. I flew on BOAC [British Overseas Airways Association] aircraft as a UM – unaccompanied minor – and greatly enjoyed, even at my young age, being fussed over by the attractive stewardesses. These days, we call them cabin crew, of course, and they are drawn from all sectors of society, with a higher proportion of male staff. But during the late 1950s and early 1960s, BOAC’s team seemed to comprise young women who were recent “debs” [debutantes]! To keep me occupied, I was encouraged to help with serving meals, and, during those pre-terrorist days, spent a lot of time on the flight deck – occasionally being allowed to watch a landing from the best seat in the house. About this time, the airline changed the equipment on the route: the supposed “whispering giant” turbo-prop Bristol Britannias giving way to the latest jetliners – De Havilland Comet 4s. Journeys became quicker and much smoother. I probably thought that I had joined the jet set, but I don’t think that membership was open to the brats of other ranks.

During these return visits to East Africa, I travelled twice on the (Beyer-Garratt-hauled) overnight train to Mombasa, where we stayed at the Silversands Forces Leave Centre on Nyali Beach, just north of Mombasa, for fabulous beach holidays. The site is now occupied by five-star hotels.

Below, left and right: Martin boarding the overnight train to Mombasa at Nairobi railway station in 1960 (left). My father with me and my brother at Silversands Forces Leave Centre, Nyali Beach, in 1960 (right).

NO QUARTER GIVEN

Even in recent times, service families, especially those of other ranks, have complained about the standard of army accommodation. The state of some married quarters, where available, and the lack of facilities in some remoter camps, have been causes of dissatisfaction. Our family did quite well for housing. My mother and father had shared a flat in London while he worked at the War Office. She moved back to her parents’ home when ill during pregnancy, and, soon afterwards, Dad was posted to Hong Kong. In readiness for our arrival in Hong Kong, he had secured a flat in one of the army’s blocks on Kennedy Road (see, for example, “PICTURE: MARRIED QUARTER, KENNEDY ROAD, HONG KONG”). The location, halfway up Victoria Peak overlooking the famous harbour, would make the value of such real estate skyrocket in later years. My brother was born in the nearby BMH Hong Kong (see “PICTURE: BRITISH MILITARY HOSPITAL (BMH) BOWEN ROAD, HONG KONG”).

Returning to Nottingham, we lived in a pleasant semi on Williams Road in the camp surrounding COD [Central Ordnance Depot] Chilwell. (These street names may stir memories for other brats.) The house looked on to a green that had been an old orchard, with pear trees and apple trees, and that backed on to a wood (known locally as “Little Wood”), where there were damsons.

When we moved to Germany, we were allocated a house in the village of Lohausen, close to Düsseldorf airport. The whole street, Braedelar Strasse, had been commandeered by the army after the war. Number 63 was a two-storey semi, with extra accommodation in a basement kitchen, plus attic rooms. A connection between the kitchen and dining room was provided by a dumb waiter, which afforded hours of fun for my brother and me: one of us would squeeze himself into it, while the other hauled him up and down. The house also had central heating – something that few people in Britain enjoyed in those days. The fruit theme continued in the garden, where we had a peach tree that seemed exotic to us, and a massive cherry tree. At first, the cherries were a treat, but as time wore on, cherries and cream, cherry pie, cherry jam etc began to pall.