To be born and grow up the child of a serving soldier gives one a unique background and upbringing, an observation that applies just as much during the twenty-first century as it did when Britain's standing army officially came into being in 1689. Perhaps the only group of British youngsters with a comparably unsettled, globe-trotting lifestyle are Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) children, but then their parents don't regularly leave home to go on long exercises or unaccompanied 'tours', nor is the risk of being wounded or killed part and parcel of their parents' jobs.

There are many downsides of being an army child, ranging from having nightmares about a parent's safety to having the worst nightmare come true, and, more mundanely, being uprooted from one's home, friends and school every year or two in order to 'follow the drum', and in this way continually having to start afresh. Yet the upsides are considerable, too: rootlessness can create independent spirits; friends may come and go, but that can breed self-reliance, while the regimental spirit, or esprit de corps, can give one the reassuring feeling of belonging to a tight-knit community. And travelling the country, and the world, is, of course, an eye-opening education in itself.

Being an army child gives one a sense of being part of history, too. When the backdrop to your childhood was India during the time of the Raj, or West Germany during the Cold War, and when one of your most vivid childhood memories is of waving your Falkland Islands-bound father off from the quayside amid a forest of Union Jacks, leafing through your family photograph album can also be like looking at personalised pages of a history book.

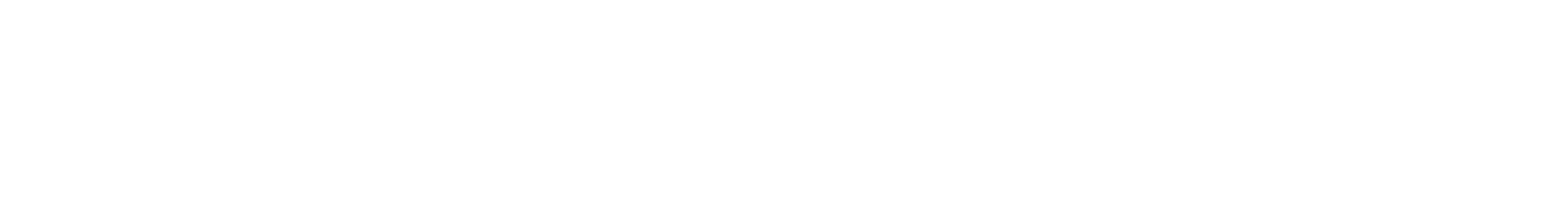

PICTURE: A SOLDIER'S FAMILY GRIEVES BY HIS GRAVE ("TOMMY ATKINS" MARRIED – PAST AND PRESENT, 1884)

The sad vignette shown below entitled 'A Soldier's Funeral' is one of the scenes that makes up "Tommy Atkins" Married – Past and Present, a composite print that was published in the 12 January 1884 issue of The Graphic (click here to see it). Appearing as it does amid images of Victorian-era army families preparing to embark on overseas postings, on the move by road and sea, and making themselves at home in married quarters, for example, it serves as a stark reminder that – then as now – a soldier's death is always a personal tragedy for the family that is left behind, especially when a child has lost his or her parent.

PERSONAL STORY: RECOLLECTIONS OF A 'DAUGHTER OF THE GUARDS'

TACA is grateful to John Tapner for contributing the following article, which was written by his late mother in 1999, when she was 93, and which was originally published in the Irish Guards Centenary Journal in 2000. Ada Evelyn Tapner passed away in October 2007, aged 100 years and 29 days.

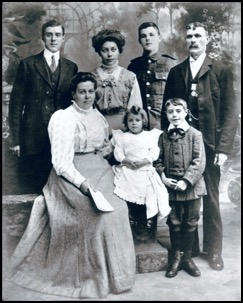

'I was born on 13 September 1907 in Westminster Hospital and was baptised by Chaplain Charles A Peacock in the Garrison of London at the Royal Military Chapel, Wellington Barracks, the second child of William Watchorn Butler and Elizabeth Josephine Butler. My father at this time was a member of the Irish Guards, then stationed at Wellington Barracks. Dad was born in Dublin and, at the age of 17, moved to England and joined either the Coldstream or Grenadier Guards, later transferring to the Irish Guards on their formation [in 1900].

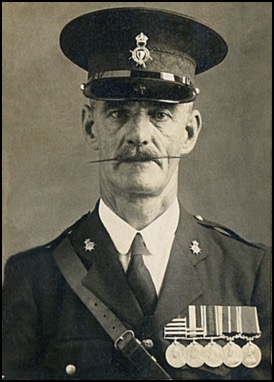

Moving to the Guards Depot at Upper Caterham (in those days Caterham was divided into Upper and Lower Caterham), we lived in married quarters until Dad's retirement after the First World War, having completed 21 years of military service. His Long Service Medal was donated to the Guards Museum by my elder brother, the late Major James William Butler. Dad, with his "Kaiser Bill" moustache, looked absolutely magnificent in his full ceremonial uniform.

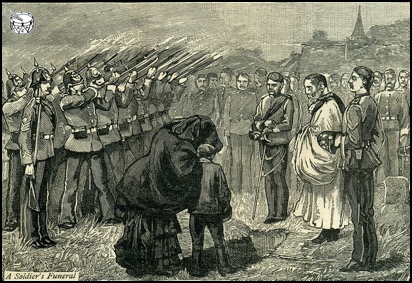

Above: Pioneer Sergeant William Butler (back), with his son, James Butler, who later became Colonel James Butler. On the right is Victor Butler, a cousin of William's.

Dad was a pioneer sergeant and, as such, was considered to be a key member of the permanent staff, who, despite trying several times, was not allowed to volunteer for active service overseas during the war. Several times, Dad had made arrangements for Mother and the family to return to Ireland in the event of his serving overseas, but, of course, this never eventuated. Dad was a very gregarious fellow and had struck up friendships with many in responsible positions. Being a "master of the quid pro quo", we always seemed to have the choicest cuts of meat in our rations. I remember Dad had four or five "bugle calls", as amongst his responsibilities he was chief of the depot's fire brigade. As a pioneer sergeant, he had a large staff, with his workshops being situated in a corner of the depot, close to our school, which was an upstairs barrack room facing Coulsdon Road and very near the gaol, the main gates and the orderly room.

Opposite the orderly room, within the main gates, was a beautiful church, which was decorated inside with historical regimental colours, many of which were torn and held together with mesh bags. I was later confirmed in this church by the Reverend James, who later became chaplain to the Forces.

When I was four, my older brother attended a school in the village. Shortly afterwards, a school was opened within the grounds of the depot. My brother, younger sister and I all attended this school. The school was opened for the children of the staff, apparently on instructions from the War Office. We were not allowed out of the depot during the war because of the risk of introducing epidemics. At the beginning of each year, all were medically examined by military doctors, and all were ordered to have a daily ration of cod-liver oil and malt. (A level dessertspoonful after our midday meal was one of the highlights of our day, and there was competition to see who could make it last the longest!)

There were two schoolrooms. The Infants School was situated at ground level, beside the cricket ground. The upstairs barrack room was for the older children. There was a large fireplace at each end of this room, but the heat was only of benefit to the teachers, as even on the coldest days, the windows were kept open and icy blasts of wind swept the room, hence the chilblains I suffered during the winter months! Our upstairs schoolroom was divided into two, with a lobby in which to hang our coats. It was equipped with a piano, one solitary picture, a poem by Rudyard Kipling called If. There was also an honours board, with my brother's name and mine printed in gold letters, each for winning first prize for copybook writing. These books were sent from the War Office to all military schools in the Commonwealth. I remember that they were issued twice more after the war, and that no more exams were held. The prize was two pounds, and we thought we were rich! The headmasters were, in succession, Mr Connolly, Mr Harling and Mr Mitchell. Friday nights were social nights, held in the Infants School and run by the headmaster and his wife. I learnt to dance (this was the time of "Sir Roger de Coverly", the "Barn Dance" and the "Lancers"), and the boys were taught chess and other interests.

Our house was an isolated, detached building, with the rear fence separating our garden from the depot and the front fence on Coulsdon Road. I have vivid recollections that, on several occasions, young officers used to use our house as a means of leaving the depot grounds without recourse to "checking out" through the main gate. They had to pass though the house as a high side gate and fence were always chained and padlocked. One of my favourite toys was a large, wooden rocking horse, which stood over 1 metre high. The young officers used to take turns "riding" this horse as they used to pass through the house. It was commonplace for all officers to be able to ride horses as mechanical transport was still in its infancy. At the outbreak of the war, all horses were commandeered by the military, those considered unsuitable being destroyed.

When we had measles or other childhood diseases, the gate in the rear fence leading into the depot was chained and locked, and even Dad wasn't allowed to come home. Our food rations were delivered over the railings by Dad's batman, who even had to do Mum's shopping at the one shop in the depot grounds. This shop used to be opposite the gymnasium. For some unknown reason, it was called the "Coffee Bar". Run by a civilian, the shop sold everything in the grocery line and was supplier to the married quarters. Adjoining the shop was a separate building used as a reading and writing room for the recruits, where they were able to purchase cups of tea and buns. The lady soldiers, called WAACS [Women's Army Auxiliary Corps], staffed this facility.

My Dad, responsible for housing the large influx of thousands of volunteers during the war, with his staff of about fifty, built a camp known as "Tin Town". This was a large collection of single-story buildings with unpainted, silver-coloured, corrugated-iron roofs. These volunteers, many of whom were miners unused to our North Downs bracing air, were initially without uniforms or housing and slept under pontoons or anywhere they could find to shelter from the weather as all available space was overflowing. These men used to fill every train arriving in the valley. Lack of transport meant that they had to walk from the station up Waller Lane, and then undertake the long walk to the depot. Mum used to boil potatoes on cold, wet nights to try to help to feed them. It was weeks before they could be fitted with uniforms. I remember that an entrance was opened to the Common over a large area to give access to Tin Town, which was located there. During the war, food became increasingly short and it was found that boiled nettles were a good substitute for spinach. Dehydrated potato flakes were developed at Kew Gardens and first tried by the married staff of the depot.

The army dug trenches opposite the Harrow Inn at Chaldon, overlooking the Weald, on the outbreak of war. These were manned as an invasion was expected. During a visit home [from Australia] some fifteen years ago, it was noticed that the indentation of the trenches was still visible.

One night, a Zeppelin came over and Mum woke us all up and let us kneel on a cabin trunk and peek from under the blackout curtains to see this Zeppelin, which was illuminated by many searchlights. It was believed that they were after the depot, but owing to the large expanse of the Tin Town roofs, which looked like a lake in the moonlight, they could not identify their position. They dropped a bomb at Kenley instead.

Even though I was only a child, because I had learnt to knit, I used to join the ladies in the church vestry, where we used to knit socks for the soldiers. It was here that I learnt to "turn the heel", which became very useful in my married life as my husband always wore hand-knitted woollen socks.

A huge fireworks display, together with illuminations, was organised to celebrate the cessation of the First World War.

After the war, for recreation, a large cinema was built adjacent to the playing fields. Each Saturday, films were sent down by train, and were picked up and driven by car to the depot, being shown the same evening. During winter, when the roads were icy, the start of the screening had to be delayed as the car had difficulty negotiating Caterham Hill. An elderly music teacher used to play the piano to provide the suitable "mood music" as, of course, these films were silent. This pianist did not require sheet music as he knew everything off by heart. Dad, as chief of the fire brigade, along with other "firemen", was always on hand during these screenings. The film frequently used to jam or break in the projector and catch fire, so it was their job to put out these fires. The admission price was one penny for children; tuppence for recruits; while the tip-up seats at the back for married staff were five pence. Of course, the film nearly always finished with the heroine (invariably Pearl White) tied across the railway tracks, with the train engine within inches of slicing her to mincemeat, only to be continued the next week. NCOs were always on hand at the end of every performance to ensure that no one left before the playing of the national anthem.

Prior to our departure from the depot, one of my final memories was listening, through a set of headphones, to my brother's crystal set, and hearing: "This is 2LO London calling. Here is the news".'

Ada Evelyn Tapner (née Butler, 1907–2007).

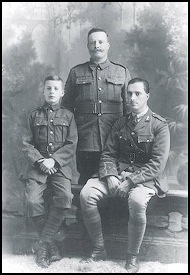

PICTURE: AN ALDERSHOT ADIEU

Four young siblings bid their father farewell at Aldershot, Hampshire. Judging from their World War I-era clothing, their daddy was in all likelihood bound for the battlefields of France.

PERSONAL STORY: BARRACK RATS OF THE PAST

'We Kirwan children, barrack rats of a bygone age, were six in all: three girls, three boys. My sister May was the eldest; I, the youngest, now in my 94th year. May was born in Carlow, Ireland, our mother's birthplace, in May 1901 (is that why she was named May?) Our father was in South Africa fighting in the Boer War when May was born, so father and daughter didn't meet until early 1906, when May and Mother boarded a troopship bound for Cairo. There, the family, as it was then, was reunited after a separation of five years, an unimaginably long time in comparison with the separation from their families of troops fighting today in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The troopship took the family on to India, to my father's new posting. There, another three children were born: Pat in 1906, Nan in 1908 and Joe in 1910. The family returned to England in 1910, where my sister Alice was born in 1910, and I, youngest of the brood as I said, in 1913. When my father was killed in April 1915 at the second battle of Ypres, my sister May was 14 years of age. My mother lost his CSM's pay and whatever extras went with the rank when he was killed. She got a pension, of course, and something for the children, but not enough to keep a cat and dog unless you were careful. To show how the authorities appreciated my father's sacrifice in dying for King and Country, they offered to send my three sisters to a school in the south to teach them to be servants; hard to believe, but true. I have the letter to prove it. This was an offence to my mother's pride, for she was a proud woman. She went to work in a laundry and left May to take care of the rest of us. It was a tough life for May, but she was a kind and wonderfully caring, attentive sister.

In 1963, my wife and I took a nine-week trip to Europe, first to Ireland, where we drove from Dublin to Carlow to visit Brewery Lane, where Mother was born. From Carlow, we drove to Cork, kissed the Blarney Stone and took the ferry to Scotland. There, we visited Loch Ness, Loch Lomond and went on to the north of Scotland, back to Edinburgh and on to Sunderland. We had our granddaughters Judy (11) and Michele (9) with us. May was a natural grandmother in taking care of them during our visit.

In 1974, brothers Pat and Joe and sister Alice paid for May to visit the States [we live in the USA] to stay with us for a month. She arrived in good time to attend Judy's wedding. Afterwards, we took May on a grand tour. Now she is gone, a lovely sister, an unbelievably kind and devoted creature.'

Dan Kirwan (1913–2010).

[See http://www.achart.ca/york/dunkirk.html for Pat Kirwan's account of the retreat to Dunkirk and http://www.achart.ca/york/marnix.html for Joe Kirwan's story of the sinking of the Marnix van Sint Aldegonde (1943) during World War II.]

PERSONAL STORY: KILLED IN ACTION

In the personal story reproduced above (see PERSONAL STORY: BARRACK RATS OF THE PAST), Dan Kirwan outlined his background as an army child. Here, Art Cockerill (whose website, http://www.achart.ca, provides in-depth information on the Duke of York's Royal Military School) expands on the devastating consequences that Dan's father's death had for his mother and siblings' financial circumstances.

'In the regimental history of the Rifle Brigade (quoted in Arthur Bryant, Jackets of Green, 1972), covering the second Battle of Ypres (22 April to 3 May 1915), appears the following passage:

There had been a certain amount of movement in the open and Captain Railston, our company commander, had given emphatic orders for it to stop. It was at this time . . . that C.S.M. Kirwan was killed. He was hit by a shell shortly after passing the bay in which I was standing. For some time he had been moving over the open, warning men to get back into the trench and not to show themselves, when this happened. It seemed particularly unfortunate that one of our first casualties should have occurred in this fashion, but it was a salutary warning to us all.

Company Sergeant Major (CSM) Edward Kirwan, a veteran of the Rifle Brigade who saw action in the Anglo-Boer War, was, as noted, among the first casualties of his battalion in action at Ypres. The effect on his family, then living in Colchester, was immediate and devastating economically. This was quite apart from the loss of a husband and the father of six children. The family had been able to live in reasonable comfort on Ted Kirwan's CSM's pay and family allowances. On the day of his death, all pay and allowances ceased.

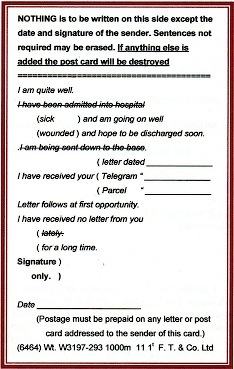

Since his departure for the front line, Mrs Kirwan had received two form postcards available to soldiers serving at the front. One, signed "Ted", is dated 7/2/14. The other, also signed "Ted", is dated 15/1/15. These cards (see the sample that appears here) conveyed the barest information to the soldier's family or a loved one. Was he well, sick or wounded? In other words, the card told the recipient that the sender was alive and little more.

Although Mrs Kirwan might have been informed by telegram of her husband's death, she received a handwritten letter dated 8 May 1915 from 15 Hanover Square, London, over the signature of Lieutenant M Biddulph, who evidently knew the family. The letter, transcribed below, is interesting for a number of reasons, not least of which is the offer of help in training Mrs Kirwan's daughters to be servants, provided that they qualified and were accepted.

Also, the boys would have the opportunity of joining the Duke of York's Royal Military School, on condition that they met the requirements for entry to the institution. As it transpired, the two youngest boys did qualify for entry and were admitted to the school, although Lieutenant Biddulph did not mention this possibility in his letter. How he came to write from Hanover Square is not known; it is possible that he was on leave from the front. This might never be known, but it is evident from his letter that he knew the Kirwan family. His letter, transcribed from the original handwritten copy, reads:

15 Hanover Sqre

London W

8.v.15

Dear Mrs Kirwan

I cannot tell you how deeply I sympathise with you in the loss you have sustained. I have known your husband so many years that it came to me as a great shock when I heard of his death. He was such a fine fellow and a good soldier. His loss will be severely felt by the Battalion. I know that nothing will compensate you for his death but at least it is good to know that he died splendidly doing his duty for his king and his country. There can be no nobler death and one that every soldier would wish for. I hope that the local secretary of the S. & S. F.A. has been in communication with you. I wrote to the Secretary at the head office in London and he says that you should receive 32/6 or 33/- a week for six months after the date of your husband's death. What happens when the six months elapse I do not know. If there is anything to prevent the S. & S. F.A. helping you, you should write to the Secretary Royal Patriotic Fund, Seymour House, 17 Waterloo Place, London SW.

You are eligible from this Fund for yourself and children. Have you applied for this? If not, do so at once stating your age, the number of children you have got and their ages. The secretary of the Royal Patriotic Fund tells me that if you have one or two girls between the age of 7 and 13, their trustees might be able to nominate them if you wish it, to the Royal United Service Orphan House for Girls, Devonport, where they would be clothed, boarded and educated, free of charges as domestic servants, until they attained the age of 16. If you would care for this please let me know and I will send for the necessary forms of application to be filled in. In view of your large family, I should not hesitate to take advantage of this offer.

I am glad to say that Mrs Biddulph is much better and now able to go out daily.

Yours sincerely

Lieut. M. Biddulph

One cannot help sympathising with company officers who had to write letters of condolence to the widows and families of soldiers killed in action. That acknowledged, it is perfectly obvious from Lieutenant Biddulph's letter to Mrs Kirwan that she was largely "on her own" following the death of her husband. Widows' benefits were minimal, and the funds disbursed by the Soldiers' and Sailors' Families Association (S&SFA, or SSFA) were not guaranteed. If anything, however, Mrs Kirwan was fortunate to the extent that CSM Kirwan died at the beginning of the Great War, when funds and places for orphan girls at the Royal United Service Orphan House for Girls were still available. What happened to the dependants of the hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors who perished in later campaigns in the war, such as the Battle of Jutland and the first and second battles of the Somme, one must leave to social historians of the period to research.

For the record, Mrs Kirwan did not choose to have her daughters trained as servants, although two of her sons were admitted to the Duke of York's Royal Military School. Instead, she left her eldest daughter, May, aged 14, to care for her younger siblings while she went out to work to keep the family together.

The permission of Danny Kirwan to publish Lieutenant Biddulph's letter to his mother is acknowledged with sincere thanks.'

© Art Cockerill, January 2008.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: AN AMAZING COINCIDENCE DISCOVERED IN ARMY CHILDHOOD

On reading a copy of the TACA-linked book Army Childhood (see below), TACA contributor Doreen McKeown (née Routledge) was astounded to spot an extraordinary coincidence, as she explains here:

Above: My grandfather in 1932.

Consequently, Mum was educated entirely in Malta, first at Floriana, then at Verdala, and was able to speak fluent Maltese – no mean feat, I can tell you: it’s a notoriously difficult language to learn.

I remember Mum telling us that she had a fabulous childhood on the island as a “daughter of the regiment”. When she reached her teenage years, she enjoyed a great social life, and became a better-than-average swimmer and tennis-player. In fact, it was through a love of tennis that she met my father, Arnold Routledge, a lance corporal in the Royal Engineers, who was also stationed in Malta, and they married in 1932, when she made the transition from army child to army wife. However, this idyllic lifestyle was destined to change dramatically with the advent of World War II, by which time Dad had been promoted to captain and they were the proud parents of five young children, when they had to endure the terrible conditions that then prevailed, with shortages of food and constant bombing becoming the norm. Mum then developed another skill: producing nourishing meals from virtually nothing, and was known to dish up a good, satisfying feed from a tin of bully beef and some cabbage!

Above, left and right: My tennis-playing mother, pictured in her youth. She lived to be 101 years of age.

However, I’m pleased to say that we all came through it unscathed, and in 1946, Dad was posted back to England and we all (now six children) followed shortly afterwards, making the memorable journey by sea on the Carnarvon Castle – a ship that had been requisitioned for military purposes – to a very different environment and, indeed, life.

Mum remained very fond of the island of Malta her whole life and returned several times as a tourist, when she relived old memories. Sadly, she died in January of this year, aged 101. She would have been thrilled to know that pictures of her and her family had been published in Clare’s book – if only I could have told her.’

We are delighted that Army Childhood has turned out to have such extra-special significance for Doreen, and thank her for having shared the news of this amazing coincidence.

PERSONAL STORY: A CHILDHOOD SPENT IN INDIA, ENGLAND AND ITALY

This former army child describes how the warmth and colour of life in 1930s' India and 1940s' Italy contrasted starkly with the cold and greyness that prevailed in England during World War II and its immediate aftermath:

'I was born in the summer of 1935 in a small town called Kasauli, which lies in the foothills of the Himalayas in India. At the time, my father, Albert George Sorrell, was an armament staff sergeant with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC), and was stationed at the Arsenal, Ferozepore. This was his second tour of duty in India. He met my mother, Peggy, at a dance when he was stationed in the barracks in Woolwich, south-east London. She was from a large Anglo-Irish family of five sisters and two brothers, and two of her sisters also married servicemen. Her father, Joseph Farrelly, had served over a number of years in the British Army, and at the time was a foreman in the Woolwich Arsenal.

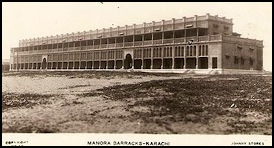

It was customary at that time for wives and children to travel up to the hills for the summer months to escape the heat of the plains, and for their husbands to remain behind. My mother was, therefore, in Kasauli when my birth was due at the end of June 1935. A few months after my birth, my father was posted to a small island off Karachi called Manora, and my mother and I travelled by train across the Sindh desert to get there. Our quarters there consisted of a beachside bungalow with a shady latticework verandah. I had an Indian "ayah" to care for me some of the time and we had other servants to cook and look after the "garden". Transport around the island was by means of a man-powered trolley that ran on "lines".

In 1939, with the threat of war with Germany looming, we returned to England on the liner The California. For a few months, we stayed with one of my mother's sisters in Kent, and I can remember the announcement of war being declared on the radio and asking what that was. Shelters were dug in the garden and we practised going down them in the evening with sandwiches and drinks and a supply of candles. It seemed quite exciting at the time. My father was then posted to the north-east of England and was involved in placing gun emplacements along the coast. We rented an unfurnished house in Scarborough, Yorkshire, and hoped to be there for Christmas 1940. On Christmas Eve, we were in the house, but unfortunately our furniture and supplies had not arrived, and when a lorry eventually arrived it turned out to hold someone else's belongings. We spent the night sleeping on the floor of this empty house, with no food or heating. I was so worried that Father Christmas would not know that I was there, but in the morning I found a small stocking with an orange and a few small items waiting for me. My mother and I (I was an only child) spent the rest of the war years in this house in Scarborough.

My father had been granted a commission in the RAOC in 1941, and had then been transferred to the newly formed Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) and served with field workshops supporting the tank brigades in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. At the end of the war, he was the deputy assistant director of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering in the Rome Area Allied Command. Early in 1946, my mother and I sailed from Liverpool on the liner Monarch of Bermuda to join him in Italy.

We left a cold, grey, poverty-stricken Liverpool early in 1946, and a couple of weeks later docked in a beautiful, sun-drenched Naples, which, from the sea, looked completely untouched by the war. My mother's sister, May, who was married to Charles Sampson, another major in REME, was already in Naples with her small son, Ivan, who was a few years younger than me, and we joined them in their villa quarters for a few days. We were then driven to Rome by an army driver, who pointed out all the sights en route, such as Monte Cassino, which had been razed to the ground by the battles that had occurred there.

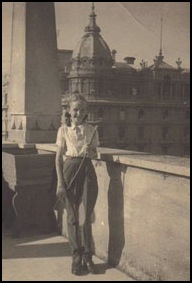

We joined my father in our quarters in the Hotel Ambasciatori, in the Via Veneto in Rome. We had been given the penthouse suite on the top floor of the hotel, which had a balcony overlooking the Via Veneto. The hotel was mainly occupied by the families of American servicemen, and I soon became friends with children from Texas and Michigan. The food was also American, and was my first taste of beef burgers, chips and tomato ketchup, which seemed like sheer luxury at the time.

I was soon to start school at the Rome Army School, where the pupils came from a number of nations because their parents worked for the United Nations Relief Organization. Each day, an army lorry (the school bus!) would collect us from outside a nearby hotel, The Eden, and would take us to the school, which was situated in a pretty villa. One day, a lady came out of the hotel and started chatting to us; she was the famous singer Gracie Fields, who was in Italy entertaining the troops. Part of our education was to visit the numerous famous sites of Rome, although we were a little too young to appreciate them at the time. We also had the opportunity of visiting the opera, and I shall always remember a wonderful performance of Carmen, which was held in the Coliseum and had real animals in the cast. It was certainly a life of luxury after the grey days of post-war England. My aunt May and cousin Ivan joined us in Rome for a while, though not in the same hotel.

After a few months, my father was posted to Venice, and we travelled with him first to the Venice Lido, where we had rooms in yet another luxury hotel overlooking the sea, and then to a hotel, the Europa, on the Grand Canal, because it was thought that the Lido would be too isolated during the winter months. The winter was very, very cold that year, and because the hotel was often flooded on the ground floor, we had to walk on planks across the floors. On New Year's Eve, there was a big party for all of the soldiers and families, and I was asked to be the mascot ("Miss 1947") and was carried in at midnight on the men's shoulders. A great thrill! Early in the new year, my aunt May and cousin Ivan also came to Venice, where they were put up in the Hotel Danielli for a short while before returning to England.

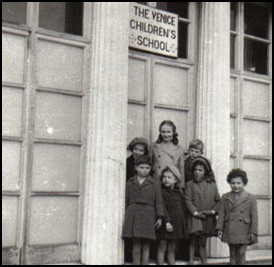

I and the other children went to another army school, the Venice Children's School. It was very tiny and the teaching was all done by soldiers. My mother and another mother were not very happy with it as we were mostly given books about the Reformation to read, and it was decided, as good Catholics, to send us two girls to a convent situated near the Rialto Bridge. This was quite exciting as we had to travel to and from it by motorboat. However, the school itself was like something from the sixteenth century. No one spoke any English, and no effort was made to communicate with us, so we were left to our own devices. Luckily, we were only there for a few months before once again moving on, this time to Trieste.

At the time, there were a lot of cross-border problems between Italy and Yugoslavia, and my father had been sent to join the British Trieste Force. We were allocated a flat in Trieste and a Yugoslav maid. Unfortunately, when the rations arrived from the NAAFI, the maid would take most of them home with her and had to be sacked in the end. (The poor girl was probably trying to feed her starving family.) She was replaced with an Austrian girl who took me under her wing and introduced me to her family. I started school at another army school in Trieste, which had a mixture of American and English children. Some of the boys were very rough and battles were fought between the English and American boys each break time. The teachers were English, however, and delighted in telling us about our wonderful empire, shown as pink on all of the maps. I'm not sure what the Americans thought of that!

About a month before my twelfth birthday, the army moved us once again to another flat in Trieste. This was supposed to be a better flat, much larger and more prestigious. However, it was very ancient and situated opposite the prison. Each morning and evening, the inmates of the prison would bang their metal mugs against the bars of their cells, creating a tremendous racket. My parents decided that they couldn't stand it any longer, and it was arranged that we would move back to our previous, much smaller and more modern flat. In a way, I was disappointed as I was hoping for a birthday party for my twelfth birthday and wanted to invite all of my friends from school, and the flat opposite the prison would have been more fun and would have given us room to run around. However, I was really glad to escape it as I felt that it was haunted and never slept well at night there.

We spent most of 1947 in Trieste, and I learnt to swim in the sea off the Miramare, which was then an officers' club. However, my father was not so lucky as he picked up a bacterial infection from the sea and had to spend some time in hospital to get over it.

At the end of 1947, my mother and I travelled by train from Trieste on our journey back to England. We changed trains at Villach, in Austria, and then continued through parts of Germany, which, from the train, you could see lay in ruins. It was quite a sobering journey. We eventually reached Rotterdam, the Hook of Holland, and for a short while were accommodated in Nissen huts while awaiting a boat to take us across the Channel, but I have no memory of that particular part of the journey, so maybe I slept through it.

We returned to a country still in the throes of rationing, and everything was in even shorter supply than during the war. We had gone from luxury and warmth to poverty and cold in just a few days. For a short while, we stayed with my mother's sister in Kent, and when my father returned, we moved to Hounslow, which was his next posting.

I would have liked to have gone to boarding school, as many of my friends from my time in Italy did, but my parents preferred to keep me with them. As I was moved to so many different schools, my education was somewhat limited, and it was difficult to keep in touch with my friends for any length of time. I was envious of my cousin, Ivan, who, when he returned to England from Italy, was sent to a boarding school in Brighton when his parents were sent out to India.

My father was posted to other places in England, including the Central Ordnance Depot in Chilwell, Nottingham, where we had a modern house in the depot and were woken each day to the sound of Reveille, while the Last Post was played each night. Later, he was sent to Tidworth, where we were allocated the most beautiful old farmhouse as a "quarter" in a nearby village. He was also sent out to Malaya [now Malaysia] for a while, but my mother and I decided not to accompany him on that particular trip. During his last posting, to Arborfield, my father helped to set up the REME museum. He had been in at the very start of the corps, so knew a lot about its history.'

Maggie Johns (née Sorrell, b.1935).

PERSONAL STORY: A WARTIME CHILDHOOD SPENT IN MALTA, 1938–46

What must it have been like to spend your earliest years being bombarded so regularly by the Luftwaffe (the German air force) that your father – a Royal Engineer – converted the family air-raid shelter into a bedroom? In telling of her childhood on Malta during World War II, Doreen McKeown (née Routledge) gives an insight into how army children seem to take the most extraordinary events in their stride. Doreen concludes her tale with a request: 'I wonder whether anybody else has any memories of their war time in Malta, which they would like to share?' If you do, please contact TACA. (For more on Doreen’s family’s story, see ‘TACA CORRESPONDENCE: AN AMAZING COINCIDENCE DISCOVERED IN ARMY CHILDHOOD’.)

'When I was born in 1938, my father was serving in the Royal Engineers in Malta, so that was how my brothers and sisters and I (five of us in all) spent our war on the island of Malta.

We were repeatedly bombed, although strangely I never remember feeling afraid. We were often short of food, but I never remember being hungry, and I guess my parents must take the credit for that.

My father was in charge of the army cold-storage facilities at the Dockyard in Valletta, and we lived in an army quarter just outside the walls of the Dockyard. As this area was a regular target for the Luftwaffe and we had to run for the air-raid shelter most nights, my father eventually converted our shelter (which was built into the rocks just opposite our house) into our bedroom. Every night we would prepare for bed in the house and then go across to the shelter to sleep. One night, our house took a direct hit, and I well remember picking our way among the debris in the morning. Needless to say, we then moved house!

Above: We children sitting amongst the rubble of our ruined house after it was bombed one night. I'm on the far right.

At one stage, we were all issued with gas masks, which caused great excitement amongst us children. I was longing for the opportunity to wear mine, although, in fact, that occasion never came – imagine being disappointed because you had no reason to wear your gas mask!

One of my clearest memories was when the Malta convoy, although terribly badly damaged, finally limped into the Grand Harbour, Valletta, bringing desperately needed supplies to the island. I was shopping with my mother in Valletta that day, and we dashed down to the harbour to see for ourselves. I have to admit that I was bitterly disappointed: I had heard all this excitement about what I thought was the "con boy", and was expecting to see some spectacular person, when, in fact, all I saw were some very bedraggled ships – it seemed to me like a lot of excitement over nothing. Little did I know!

I'm very happy to say that we all survived the war, and I well remember the great excitement when victory was announced. We were then living in a house in the St George's Bay area. This house was contained within a compound, which was surrounded by a moat – it was called St Andrew's Fort. The moat used to fascinate us children. Our brothers, being a bit older, were allowed to go down in it to catch butterflies, which was their hobby, but we girls weren't allowed down there and were very jealous of our brothers. This compound contained an army workshop, and German prisoners of war were often brought here to work. I remember us children taking them drinks and showing them our books (we tried to teach them some English words from these books, with limited success, as I remember). We certainly didn't regard them as ogres – they were always very nice to us, and we probably reminded them of their families at home.

We children were asleep in this house one night when our parents woke us up so that we could go up on to the flat roof to watch the firework display to celebrate the end of the war. I also remember the great excitement when King George VI came to the island and we all lined the streets waving small Union Jacks.

I've always felt a great affinity for the island of Malta and its people, and have returned there many times since as a tourist, thoroughly enjoying searching out the old haunts that I remember from those childhood days. St Andrew's Fort, for example, still exists: it's now the administrative offices of a school. I've visited it in recent years, and it certainly brought back a lot of happy memories.'

Doreen McKeown (née Routledge, b.1938).

PERSONAL STORY: PICTURES FROM A 1940S’ ARMY CHILDHOOD IN THE BRITISH MANDATE OF PALESTINE, EGYPT AND SOUTH AFRICA

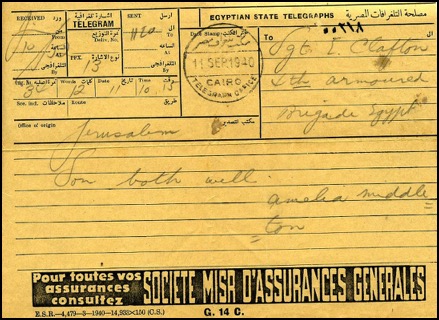

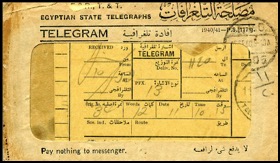

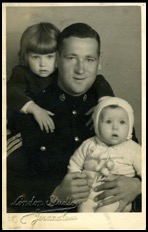

Above and below, left and right: The happy news of my birth in Jerusalem was sent to my dad, who was in Egypt at the time (note the ad, even in those days . . .) (above); the fateful envelope in which the news arrived (below left). Taken in Jerusalem, this photograph (below right) shows me in a fetching knitted garment, with my sister, Elaine, on my dad’s back.

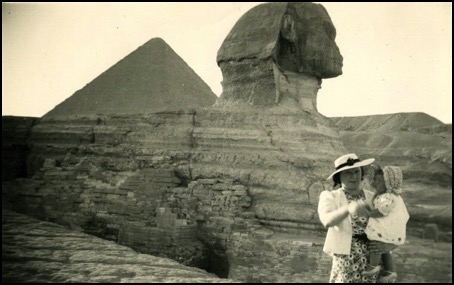

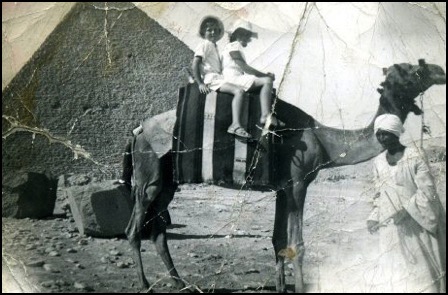

Below: My sainted mother and Elaine, probably before we went to South Africa. There is no doubt about the location.

Below: On our evacuation from Egypt, we ended up in this private hotel a stone’s throw from the beach in Durban, South Africa.

Below, left and right: Me and Elaine by the hotel (below left). The two of us in front of an exotic bush with a Mrs Garvie, who may have owned the hotel (below right).

Below, left and right: I’m not sure where this was taken, but I doubt that General Rommel would have been put off (below left). This is me leaping fearlessly into Lake Timsah. Despite appearances, I was, in fact, clothed (below right)!

Below: This poor battered photo later accompanied me to school many times to prove that I had been in Egypt.

Above and below: After the war, my dad was involved in the running of a prisoner-of-war (PoW) camp for soldiers of the Afrika Korps, and probably some Italians. This is it (above). The gardener (a PoW) was obviously very proud of his garden. Dad and a few others (below), including a senior officer (seated), by the PoW camp (which was called Amariyah, or similar).

David wonders whether anyone remembers him from that time, and says that he would ‘love to contact any of my peer group or descendants of Mrs Garvie’. If you’d like to get in touch with David, he can be e-mailed at dave.clafton@gmail.com.

PERSONAL STORY: 'EVER HEARD A SHOT FIRED IN ANGER?'

In answer to the question posed above: Chris Fussell has, when he lived with his family in Egypt. (And for more on his army-child experiences, see 'PERSONAL STORY: BULLFROGS, CICADAS AND MACHINE-GUN FIRE IN EGYPT, 1951', below; 'PERSONAL STORY: WARTIME IN THE UK; PEACETIME IN MALTA, EGYPT AND OXFORDSHIRE', 'PERSONAL STORY: EXPERT FIRST AID IN MALTA' and 'PERSONAL STORY: MAYHEM IN A MALTESE MARRIED QUARTER' on the 'MEMORIES & MISCELLANEA' page, as well as 'PERSONAL STORY: A MARRIED-QUARTER CRISIS IN EGYPT' on the 'ACCOMMODATION' page and 'PERSONAL STORY: MY EDUCATION AS A MARRIED-QUARTERS' CHILD' on the 'SCHOOLING' page.)

'In my case, I was eleven, going on twelve, in late 1950. We lived in Arashieh, a suburb of Ismailia, on the Suez Canal; a bit close to Arab Town, the "shantytown", though. We had a nice flat, one in a block built speculatively by local Greek entrepreneurs for renting to soldiers' families for whom there was no room in the nearby garrison, Moascar. My big sister worked in Moascar as a civilian on the military telephone exchange. Dad's Pioneer unit was a little further away, at El Kirsh.

My dad and sister had gone into work normally, very early that morning. I went down at 8 am to get on the school bus, only to be told that it would not be running and to get myself home and stay there. I had time to work on my new Hornby Dublo train set, then. Mum was a bit more worried because she had been following in the papers and on the radio news the political moves by Egypt to get rid of us from the Suez Canal Zone (we had been there for seventy years). The day before, the Egyptian government had abrogated the Canal Treaty of 1936, effectively our "tenancy agreement".

Mum was looking out of the front window, when a nondescript chap on a bike went by, warning everyone urgently, and in English, to close their shutters. No sooner had we done this, when a barrage of bricks hit them. Our neighbour, Mrs Lunt, who was all alone with her small baby, came knocking to ask if she could come in with us. When she did, we all went back to the kitchen. Because of the baby, we put the dog in the next room, the broom store. There was a lot of shouting, and then the front door was broken into. Next, we heard the sound of an Arab mob looting the place, ripping out fittings and taking everything movable. They came towards the back rooms, but Rex, our dachshund, started to bark up a storm. They were frightened and kept away, not knowing that the unseen dog stood only 8 inches high. (I have had a high regard for dachshunds ever since!)

After three or so hours, the noise abated. Pretty soon we were sure that they had left the flat, although perhaps not the block. So we stayed put. Then some mob noise returned, accompanied by the sound of shots – single and automatic bursts – and the howling engine and transmission noises of military vehicles. After that came the unmistakable crunch of British Army boots, and an anxious young corporal of the Lancashire Fusiliers persuaded Mum and Mrs Lunt that it was safe to come out.

We had lost everything, except what was in the kitchen, yet we had got off lightly. There had been a few deaths, and one or two rapes that an eleven-year-old boy was not supposed to know about. It was not all one-sided, though. Mr Lunt came home to the flat next door, found his wife and baby missing (he did not think to ask us where they were) and shot the looters that he found in his flat. (Young lads out for a lark? They were in the wrong place at the wrong time.) That night, and for many nights after that, we heard the chorus of machine-gun fire, punctuated by the flat plopping of mortars and the occasional crack of anti-tank guns (these were especially effective against the mud walls of Arab Town).

A scarring experience? Not really. For over fifty years I have kept my liking for Arabs in general, and for Egyptians in particular. And the happiest years of my later time in the army were spent surrounded by sand and palm trees.'

Chris Fussell (b.1939).

PERSONAL STORY: BULLFROGS, CICADAS AND MACHINE-GUN FIRE IN EGYPT, 1951

In 'PERSONAL STORY: 'EVER HEARD A SHOT FIRED IN ANGER?'' (see above), Chris Fussell describes the day that his family's flat in Egypt was looted by a mob. Here, he recalls what life was like in the aftermath of the riots in Ismailia. And for more about Chris' time as an army child, see the 'MEMORIES & MISCELLANEA' page ('PERSONAL STORY: WARTIME IN THE UK; PEACETIME IN MALTA, EGYPT AND OXFORDSHIRE', 'PERSONAL STORY: EXPERT FIRST AID IN MALTA' and 'PERSONAL STORY: MAYHEM IN A MALTESE MARRIED QUARTER'), the 'ACCOMMODATION' page ('PERSONAL STORY: A MARRIED-QUARTER CRISIS IN EGYPT'), and the 'SCHOOLING' page ('PERSONAL STORY: MY EDUCATION AS A MARRIED-QUARTERS' CHILD').

'The riots had been quelled in Ismailia, in the Suez Canal Zone, in 1951. Army and RAF families living in off-garrison, overflow "private hirings" – flats and houses – felt a bit safer with British soldiers and armoured vehicles patrolling the streets and sandbagged checkpoints at street corners. The beautiful "XX" flag of the Lancashire Fusiliers floated above our local, off-garrison NAAFI shop, where they had their tactical HQ. We went daily to school on buses with guards carrying Sten guns – not shot-guns. (During this emergency, Dad was disgusted to be issued with a bit of string as a sling for his personal weapon, an old .303 rifle, but with his smart bearing still looked every bit the hardened old soldier.)

We had been accustomed every night in Ismailia to hearing an evening chorus of bullfrogs croaking in the myriad irrigation channels, with a shrill descant from cicadas in the dry grass on the dusty desert fringes, which started at the town's limits. Then we had machine-gun fire every night. Hearing this excited us little kids and worried Mum, yet Dad told us that it was mostly nervous sentries firing at shadows. Some casualty reports filtered in, though. Several hundred British servicemen eventually died in the three or four years of the Suez Canal Zone Emergency, more than in the Falklands in 1982. Was it dangerous for us married-quarters kids? Well, we just got on with enjoying Egypt's sunshine and beaches and school, which was from only 9 am till 1 pm daily!’

Chris Fussell (b.1939).

PERSONAL STORY: THE HUNGARIAN UPRISING, OCTOBER TO NOVEMBER 1956

Terry Friend, whose father was in the Royal Horse Artillery, was living in Hohne, in (West) Germany, when the short-lived Hungarian uprising against Soviet rule began on 23 October 1956. Here, he recalls that tense Cold War episode from his childhood perspective. (For Terry's memories of the camp at Hohne, click here; to read about his family's married quarters in Hohne, click here; for his recollections of his schooldays in Hohne and Wilhelmshaven, click here; for his reflections on Remembrance Day, click here; for his account of Christmases in Germany, click here; and for more about Terry himself, visit his website: http://www.anothercountrysong. com.)

'The family was gathered in the kitchen, seated at the table and partaking of a meal. There was a certain tense atmosphere in the room, and as young as I was, I could sense that something was up. Eventually Pop cleared his throat, and, as the meal neared its end, spoke to us, leaning across the table as he did so. "Children, I have got something to tell you." Allowing that to sink in, he continued: "I may have to go away for some time." He paused for a moment, and then mother butted in: "The whole regiment may have to go". Gradually, the story began to unfold. The people of Hungary had risen in an armed rebellion against their Russian masters and had appealed to the free world for help. The Cold War was at its height. Only a few short years previously, our country had been involved in the Korean War. Now there was a potential threat almost on NATO's doorstep. Pop's regiment was on stand-by with the rest of the British Army of the Rhine [BAOR]. Now it was up to the politicians to get things moving. For the next few weeks, the atmosphere was almost electric. We heard reports daily of the tragic events unfolding not so very far away from our German home. As the world very possibly teetered on the verge of yet another European conflict, it was all very exciting for my brother Chris and I, innocent as we were.

There was one more thing from those dark days that sticks in my mind that I found rather strange at the time. The garrison commander had banned all bonfire celebrations that year out of respect for the events that were currently taking place in Hungary. We children, who looked forward to the annual bonfire celebrations of 'Guy Fawkes Night' with almost the same passion as we did for Christmas, were very disappointed. Although I felt sorry for the Hungarians, I could not see that missing out on our fireworks was going to be of any help to them at all. Pop must have felt the same way, for a few days after November the Fifth, he lit the bonfire and we let off our fireworks.

The bonfire had, in fact, been lovingly constructed for some weeks prior to the occasion for which it was required. All of the families in the block got together for this annual event. Sausages and hot soup were the order of the day; the fireworks were all pooled together and the dads took turns lighting them. We always had a huge bonfire, which used to burn for most of the night. Chris and I (with a lot of help from mother) always made a guy, which we proudly placed on the top of the bonfire: Mother used to sew some of our old clothes together, and Chris and I had the job of stuffing him with newspaper. The high point of the night for me was the moment when the guy tumbled into the raging inferno below – it was macabre, perhaps, but I always imagined him screaming as he toppled into the hungry flames.'

Terry Friend (b.1947).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70

Leslie Rutledge's father served in the Royal Engineers between 1948 and 1970, during which time his wife and growing family accompanied him on his postings to England, Europe and the Far East whenever they could. Twenty years of army life and eight children make for a long and eventful account, and you can read Leslie’s richly illustrated, eleven-part story by clicking here (and here for his personal observations on an army childhood.

PERSONAL STORY: MY ARMY CHILDHOOD IN EGYPT, THE UK AND SINGAPORE

We have always enjoyed the photographs posted by Lynne Copping (née Wilson) on TACA’s Facebook page, and were delighted when Lynne agreed to tell us not only about her own life as an army child, but also about her family’s long-standing links with the British armed forces. As Lynne initially explained: ‘I come from a service family, as did my father and my grandfather. We all have an Egypt connection: I was born there (before being evacuated in 1951, with twenty-four hours’ notice); my father was there in 1935 as a small child, while his father was in the RAF; and my great-grandfather won his Egypt medal at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir while serving with the Grenadier Guards. Various aunts and uncles were in all three services; my three brothers were in the army; I was in the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF), and, having married a soldier, my children were army children in Germany’. We are immensely grateful to Lynne for her willingness to share her family’s story – read on for more, and see below, ‘PERSONAL STORY: FROM ARMY CHILD TO SERVICEWOMAN TO ARMY WIFE AND MOTHER’ for the second instalment.

‘I come from four generations of service families, and when I first started sorting out my photographs in order to tell you about my life as a service child, I didn’t realise how significant the place of my birth, Ismailia, in Egypt, would be. My great-grandfather, Richard Wilson, was in the Grenadier Guards and fought at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir, in Ismailia, in 1882.

My grandfather, Richard Edward Wilson, joined the Royal Flying Corps and was posted to RAF Leuchars, in Scotland, where he met my grandmother, a local Burntisland girl. He was posted to Ismailia in about 1930, to Abu Sueir and Heliopolis, taking his family with him. My father, Richard George Wilson, lived in Egypt as a small child and went to school there.

Below: My father as a boy, with his older sister, Nina, and younger brother, Ken, in Heliopolis.

By 1941, my grandfather had been promoted to flight lieutenant, and my aunt had joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). My father joined the army in March 1942 as a Gordon Highlander when he was just seventeen, by giving his age as nineteen. Within a month of joining, he was informed that he and the other young soldiers were being transferred to a young soldiers’ regiment, the Highland Regiment. In November 1942, this regiment was disbanded, and, after a variety of tank-crew jobs, my father volunteered as a sergeants’-mess waiter as this meant that he would be warm and dry.

About a week after that, it was announced that volunteers were required to train as glider pilots for future invasions, and as he had always wanted to be a pilot, he volunteered and was tested for suitability. He completed his training, was awarded his wings, and was promoted from corporal to sergeant in time for the Battle of Arnhem, in the Netherlands, in September 1944. My father has written an excellent account of his experiences in Arnhem, which tell the story in detail, but briefly, while spending three days in the cellar of a house in Oosterbeek, he wrote his name and address on the cellar wall, and they are still there to this day, as reported in the Ellon Times in September 1994, the fiftieth anniversary of the battle. He escaped unscathed when he escorted eleven assorted infantrymen to the Lower Rhine, where they were evacuated by Canadian engineers. (He always said that Arnhem was a nine-day wonder, but that Borneo was scary!)

Having returned to Down Ampney, in Gloucestershire, he married my mother a few weeks later. Thereafter, he was posted to India (to 669 Squadron, Army Aircraft Corps) – by then, his father was a wing commander in the RAF, and they were able to meet up while in India – Palestine and then Egypt, which brings us back to Ismailia, in 1948. The Glider Pilot Regiment having been disbanded, I think he was in the Royal Artillery by now, but in Egypt he discovered that Military Provost Staff Corps (MPSC) personnel were entitled to married quarters, so he transferred to that and applied for my mother and older brother, Richard, to join him. They accordingly sailed out on the SS Empress of Australia in May 1949.

MY EARLY YEARS IN EGYPT, SCOTLAND AND ENGLAND

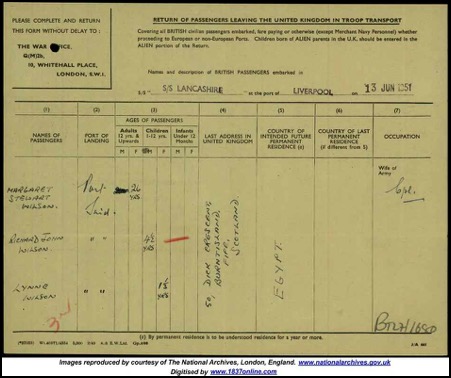

I was born in the British military hospital at Moascar in 1950, and we lived in a house with a tented roof that we shared with another couple, there being a shortage of married quarters. I was christened in St Margaret’s, the Church of Scotland church in Moascar. In February 1951, we returned to Burntisland for a few months’ holiday, sailing on the HMT Empire Trooper from Port Said to Southampton, arriving on 9 March. We returned on the SS Lancashire, leaving Liverpool on 13 June 1951.

Above: My mother was twenty-six, my brother was four-and-a-half, and I was “one-and-a-third” years old when we sailed from Liverpool on the SS Lancashire.

My father did not like the MPSC as he was a very gentle man and did not enjoy having to be stern at work. He said that seeing men on boats on the Suez Canal appealed to him, so he joined the Royal Army Service Corps’ Water Transport Division.

My brother Stewart was born in August 1951, and soon after that the trouble in Suez escalated. My older brother, aged four at the time, remembers playing near the door to our house, with two soldiers on guard duty nearby, when three terrorists jumped over the wall to attack them. The soldiers shot one of the men and then ran off after the other two, leaving the dead man on the ground – very traumatic for a young child.

Below: The Suez evacuation, 1951.

In November 1951, my mother was given twenty-four-hours’ notice to leave Egypt, with a four-year-old, an eighteen-month-old, a nine-week-old baby and one suitcase. On leaving the house, she picked up a metal pail of nappies that were steeping as she wasn’t going to go on a four-week sea voyage with no nappies! We set sail on the SS Charlton Star, leaving my father behind. The prams were all roped together on deck, and by the time that we reached Southampton, they were a solid, rusted mass. On arrival in Southampton, we were given vouchers with which to buy some warm clothes and rail warrants to get us home to my mother’s parents in Burntisland.

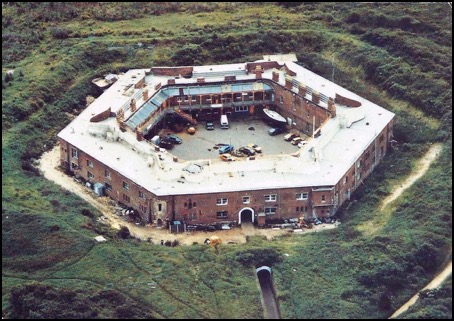

We rented a house in Burntisland, and when my father returned from Egypt in July 1953, we moved to the Isle of Wight, where he had been posted to Fort Victoria and then to Fort Golden Hill, the training base for the Royal Army Service Corps’ Water Transport Division. We lived in very basic married quarters at Fort Victoria, with no plaster on the walls – just distemper over the bricks – with no bathroom and an outside toilet. (The married quarters are now exclusive cliff-top holiday homes and the fort is a country park and marine aquarium.) We then moved a few miles away to Fort Golden Hill, a unique hexagonal barracks constructed between 1863 and 1868 as one of the Palmerston forts to defend the English Channel. The married quarters here, in Monks Lane, were two terraces, with narrow front gardens and small backyards housing the outside toilet, with a tin bath hanging on the back of the door. My youngest brother Graham was born here.

Below: Fort Golden Hill.

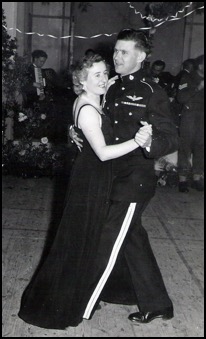

Below left: My parents, Rita and Dick Wilson, pictured at a Christmas party at Freshwater in 1954. Below right: My brother Stewart at the back of the Monks Lane quarter in 1955.

Below: This is me pictured outside our Monks Lane quarter. I am wearing a dress that my mother made from parachute silk.

We moved to Portsmouth, Hampshire, in 1957 and stayed for a few months in Milldam Barracks, where I went to the garrison school. We then moved to Hilsea Barracks, where I went to another primary school, my third by the age of seven. The roads being named after World War I battlefields, we lived in Bapaume Road, and the road next to us was Peronne Road.

OUR POSTING TO SINGAPORE AND LIFE ON PULAU BRANI

In May 1958 we were posted to Singapore. The flight, in a Hermes from Blackbushe Airport, near Camberley, in Surrey, took three days, with an overnight stop in Karachi, Pakistan. The first stop was in Brindisi, in Italy, where we had a meal in the airport restaurant. It was a long, tiring journey with three young children. (My parents had been told, wrongly as it turned out, that the secondary schooling in Singapore was not very good, and as my older brother had just passed his Eleven Plus, he stayed with my grandmother in Burntisland and went to Kirkcaldy High School.) On arrival in Singapore, we stayed for a few weeks at a hostel while waiting for our married quarter, and I went to my fourth primary school. Our living accommodation consisted of basic, small chalets, with a little kitchen, with no fridge – just an icebox – and meals being taken in a central dining room.

We then moved to the small island of Pulau Brani, a couple of miles long, in the middle of Singapore harbour. Pulau Brani was the headquarters of the RASC’s Water Transport Division. Our first house was at the end of a terrace, up a really steep hill, with servants’ quarters behind for our amahs, who didn’t live in. (Some of the local people, including our amah, lived in kampongs – villages – on stilts over the sea.) Further away from the house, down a covered walkway, was a row of outside toilets, Elsan chemical ones, which were emptied daily by an old Chinese man who had a bicycle with panniers on the sides. Frequent visitors were my father’s brother, Ken Wilson, who was in the merchant navy, with the Ben Line, and his cousin, Harry MacIntosh. We saw more of them when we lived in Singapore than we did in the UK. The highlights of their visits were when we went to have lunch on their ships in Keppel Harbour. Our house faced the harbour, and if my uncle’s ship berthed at night, my father would send him a message in Morse code by switching our verandah light on and off. He would also speak to his friends in Morse code if he didn’t want us to understand him. My parents also spoke to one another in back slang ("pig Latin") if they didn't want us to understand them, but my brothers and I had become fluent in it by about the age of six.

When we first moved to the island, the primary school, which was run by the British Families Education Service, was on the neighbouring island of Blakang Mati (which is now the holiday island of Sentosa), and we had to travel there by ferry and then a 1-ton truck. This was my fifth school. The school then moved to Pulau Brani by taking over an officer’s house and converting it to a three-roomed school. There were about twenty-eight pupils, and army children from Blakang Mati, including the Gurkha children, then came to us by ferry. This was my sixth school.

Below: A sports’ day at the Pulau Brani primary school.

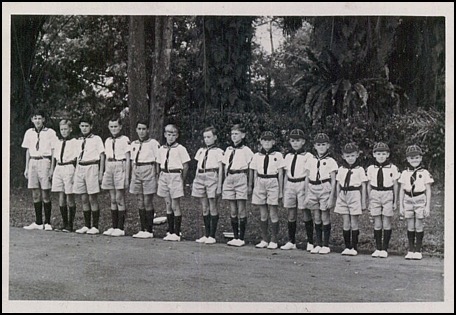

We would go on picnics at the weekends to deserted islands, travelling by small landing crafts. Excitement came to the island when the famous underwater explorer Hans Hass, with his wife Lotte, visited on his yacht, Xarifa, and we were allowed on to it; he left Xarifa with 37 Maritime Company for a while. A Sea Scouts’ troop was formed on Pulau Brani, and boys from the mainland joined the older boys on the island. The younger ones wanted to join in, too, so a Sea Cubs’ troop was also formed.

Above: Pulau Brani’s Sea Scouts and Sea Cubs.

We then moved to a bigger house on the island, again with chemical toilets located away from the house, and with the amah’s quarters at the back. Material was cheap, and my mother kept herself busy by sewing all our clothes and fancy-dress outfits. As a navigator on the army’s landing crafts, my father was away from home a lot with the landing crafts, taking supplies upcountry to various places in Malaya [now Malaysia], such as Penang, Terendak and Malacca. The Malayan Emergency was taking place at this time, though he never spoke about it.

ATTENDING PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN PORTSMOUTH

In December 1960, we returned to the UK, staying in Burntisland for a few weeks while we waited for our married quarter in Portsmouth to become available. While we were there, I went to Burntisland Junior School. This was my seventh primary school. We then moved to Burnaby Road in Portsmouth, opposite Milldam Barracks, where we had lived before. Here, I went to St George’s Junior School. This was my eighth and last primary school. I had been at the school for two months when we sat the Eleven Plus, and I passed it, along with one other girl – not bad in view of my disrupted education. My next school – my ninth – was consequently the local grammar school in Portsmouth.

My father worked at St George’s Barracks in Gosport, which he would travel to by ferry, the landing crafts being berthed at HMS Vernon, a short walk from our house. Once again, we didn’t see much of my father, who was away with the landing crafts, going to Fremington, in Devon, and making many trips to Benbecula and St Kilda, in the Outer Hebrides, taking ammunition and stores there. In 1962, Hammond Innes wrote his novel Atlantic Fury, and was allowed to accompany my father to St Kilda to gather information for it.

RETURNING TO SINGAPORE

We were posted back to Singapore in November 1963, again without my older brother, who was starting a three-year apprenticeship to be a telecommunications technician in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) at the Army Apprentice College at Arborfield, in Berkshire. After a short stay at the Savoy Hostel again, we moved back to the island of Pulau Brani – to the same house, with the same amah. It was as if we had never been away, except that the houses had since been modernised and we now had indoor flushing toilets and windows with glass (instead of chicken wire and wooden shutters).

I now attended my second secondary school, Alexandra Grammar School, which was again run by the British Families Education Service. This school was accessed by a flight of many stairs, which must have kept us very fit. School was mornings only, from Monday to Saturday, with extra activities in the afternoons if required. Everyone over the age of twelve had to carry an identity card with them at all times in Singapore, so I kept mine in my school pencil case. In September 1964, the school system changed, becoming comprehensive, and so we moved into the brand-new buildings of St John’s Comprehensive. (The school is now the United World College of South East Asia, and some of the original school buildings still exist, especially the iconic hall, with its many-pointed roof, which is now a listed building.)

THE INDONESIAN CONFRONTATION AND CIVIL UNREST

Confrontation between Indonesia and Singapore took place between 1962 and 1966. My father was involved in this effectively undeclared war, navigating his landing craft up and down the coast of Malaya and Borneo, offloading ammunition and supplies. I think that it was during the Easter holidays of 1965 that a curfew was declared. We were not allowed to leave the island at all, and were not permitted to be outside our houses between 6 pm and 6 am. My brother had been on the neighbouring island of Blakang Mati, visiting a school friend, and an army duty boat had to be sent across to bring him back. Groceries were delivered to us by scooter from the NAAFI shop, and fresh bread was supplied to us by the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. We could go outside during the day, but were not allowed to leave the vicinity of the married quarters, even to visit friends who lived in a different part of the island. My brothers and I played endless games of badminton and hopscotch outside the house, and board games inside. We had a television, but programmes didn’t start until the evening, and the English programmes were few and far between. What really annoyed me was that we got to have a week or so off school, but then we would have been on holiday anyway. Why couldn’t this have happened in term time?

Those of my friends who lived on the mainland had different experiences of this crisis, as they were closer to the terrorist attacks that were taking place. There was also civil unrest going on at the same time. One friend’s mother was rushed to BMH Singapore after suffering a haemorrhage shortly after the birth of my friend’s baby sister. She had to be escorted in an ambulance under armed guard due to civil riots in Singapore between the National Chinese and the Red Chinese in July 1964. My friend had to go to collect her baby sister as she was not allowed to be readmitted. Whilst on the way, under armed escort in a Land Rover, she witnessed a lot of burning cars and sensed a feeling of grave unrest. It was exciting, but quite frightening. The British military hospital was open only for emergencies and for deliveries of clean linen.

One sad consequence of the confrontation was that one of the former Gurkha schoolboys from the grammar school was killed in Indonesia. Lachhin Gurung, who had joined the 6th Gurkha Rifles in 1963, was involved in the Indonesian Confrontation as a rifleman. When the enemy was sighted in his area, he was sent on a patrol with his section. Unfortunately, his section was ambushed. His patrol commander (a sergeant) and he were killed in the crossfire that ensued. When the Indonesian patrol left, Lachhin and his patrol commander were beheaded. The sergeant and Lachhin’s bodies were brought to Singapore to be buried with full military honours. All the Gurkha boys from Alexandra Grammar School attended the funeral.

EVERYDAY LIFE IN SINGAPORE

Otherwise, life carried on as normal for us. We teenagers mostly ignored those affairs of global importance that were going on around us and concentrated instead on schoolwork, fashions and pop stars. The Rolling Stones came to Singapore in February 1965, and I was one of the ardent fans that went to see them. My brother and I then went to the hotel where they were staying and got their autographs. My mother did a little shopping on the island, but a large shop meant going to Singapore by ferry and then taking a taxi to the market and larger shops. If she missed the ferry on the return journey, she would get in a little sampan to cross the harbour and then beg a lift from the duty driver to take her and her shopping home. We never had that luxury on the return from school, having to walk, which was hot and humid if it was dry, and hot, humid and wet if it was the monsoon season.

Quite a few of my friends would travel upcountry in Malaya during the holidays, to places like the Cameron Highlands or the waterfalls at Kota Tinggi, but we didn’t. My father was away such a lot that when he did get leave, he had probably just returned from Penang, Malacca and such places, and just wanted a rest at home. The landing crafts had Malay and British crews, with the Malays wearing the traditional songkok instead of a beret. These men were trained on Pulau Brani. In 1965, the RASC amalgamated with other corps to become the Royal Corps of Transport, and a large parade was held in Singapore, at Gillman Barracks.

The social life in the army was excellent, and the parties and dances continued. My mother again had plenty of time for sewing. But in June 1966, she became seriously ill and was admitted to BMH Alexandra, the military hospital. Even so, she still managed to hold her coffee mornings, with her friends bringing flasks to her bedside. But then she had to be "casevaced" back to the UK, and although it was only a couple of weeks before I was due to sit my O’ levels, we packed up our quarter and flew back to England.

BACK TO THE UK AND THE END OF CHILDHOOD

On our return to the UK, my mother was admitted to the Louise Margaret Hospital in Aldershot, Hampshire, and we moved into a temporary married quarter at Fort Widley, just outside Portsmouth. I returned again to the Southern Grammar, only to be told that I could not sit my O’ levels as I had been following the University of London syllabus and the school in Portsmouth used a different one. After the summer holidays, we moved back to Milldam Barracks – to a different block this time – and I dropped down a year at school so that I could sit my O’ levels the following year. By the Christmas, though, my mother was getting worse, so I left school to stay at home and be with her. By this time, my older brother was in the army in Germany, and my younger brothers were at boarding school. My father was still away a lot with the landing crafts (he transported many different items, delivering a generator, for example to the Channel Islands in 1968), so we didn’t want my mother to be alone, even though she spent half of each month in hospital in London.

Although I had no O’ levels, in about March 1967, my mother said that I should think about getting a job. I had wanted to be a teacher ever since I was in primary school, but was soon disillusioned by the old-fashioned and rude attitudes of the teaching staff at the school in Portsmouth. My mother suggested that I become a bank clerk, so I promptly made an appointment to see my local bank manager and told him that although I had no qualifications, I was fairly bright and would like to work for him. He was a bit taken aback as I think he had thought that I had come to open an account. His response was that although he had no openings just then, he would think about it, and a few weeks later I received a letter saying that I could start at a small sub-branch in Portsmouth.

My mother died in the May of 1967, which was devastating to the family. My youngest brother was only ten at the time.’

Lynne Copping (née Wilson, b.1950).

PERSONAL STORY: FROM ARMY CHILD TO SERVICEWOMAN TO ARMY WIFE AND MOTHER

Lynne Copping’s army childhood saw her travel with her family from Egypt, where she was born, to postings in the UK and Singapore (see above, ‘PERSONAL STORY: MY ARMY CHILDHOOD IN EGYPT, THE UK AND SINGAPORE’). By the late 1960s, she had left school and was about to begin a new phase in her life. Lynne now takes up the tale.

‘I and my brothers followed in the family tradition of joining the services. After my mother’s death, my oldest brother was still in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) in Germany, and was then posted to Arborfield in Berkshire. I joined the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) in August 1969, and my younger brother went to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst in September 1969. In 1972, my youngest brother went to the Army Apprentice College at Arborfield to begin his training as a helicopter engineer in the REME.

Above: Me, my father and my brothers at Arborfield in 1972.

I did my basic training at RAF Spitalgate, near Grantham, in Lincolnshire, living for six weeks in a twelve-bedded room. Trade training, to be a statistics clerk, was at RAF Credenhill, near Hereford, where we were eighteen to a room. After that, I was posted to Swanton Morley, in Norfolk. I worked in engine records for the air photography fault-reporting and analysis system, fault-reporting on aircraft cameras – this was my best job in the RAF. My social life included fancy-dress parties and club membership, such as of the Auto Sports Club (I was on the front and back cover of their magazine). My brother was still at Sandhurst at this time, and I would sometimes get an invitation to a ball from him, with the request to bring some friends as his friends were without partners.

MARRIAGE, 669 SQUADRON AND LEAVING THE WRAF

In April 1972, I was posted to RAF Wildenrath, in Germany, where all the buildings were camouflaged. I worked on the Harrier servicing flight and undertook defect-reporting on Harriers, all pre-computers. In the summer of that year I met my future husband, who was a REME helicopter engineer with 669 Squadron Army Aircraft Corps (AAC), and discovered that his brother was also an army helicopter apprentice at Arborfield. I wrote to my brother and asked him if he knew Roger’s brother, and although he was in the intake above him, he did. I got engaged and we married in the Church of Scotland church at RAF Wildenrath in January 1973. All our friends and relatives hired a coach and came over to Germany for the wedding. With all the drinks being duty-free, they had a wonderful time.

A few months after our wedding, I received a letter from my father telling me that he had been posted to 669 Squadron in India during World War II, after he had been at Arnhem. My parents had had a very exciting honeymoon, with my mother chasing his squadron around Essex. A week or two later he was posted to India for three years, to 669 Squadron, where the men were training to glide into Burma, to disrupt the railway, and then to find their own way home. Luckily for him, the war ended in the August of 1945, while they were still training. A week or two after I received the letter from my father, my husband came home from work and told me that the squadron had just received, from a previous officer commanding (OC), a large squadron photo dating from 1945. I went straight to the OC of the squadron and asked if I could see this photo because my father might be on it. And there he was: right in the middle of the back row, distinguished by his beret amongst all the forage caps (it was a joint RAF and army unit).

l left the WRAF because a civilian job became vacant in my office and I was fed up with playing war games while my husband didn’t. His was a VIP unit, and they didn't take part because they weren’t officially there, so whenever there was a taceval (tactical evaluation) and we all had to put on our NBC (nuclear, biological and chemical) suits and gas masks and sometimes had to work shifts in an underground bunker, he just carried on as normal. I had great difficulty with wearing a respirator as I was very short-sighted and had to remove my glasses before wearing it, rendering me almost blind.

HOME-OWNERSHIP, MOTHERHOOD AND LIFE IN GERMANY