Nowadays, army children are taught in proper schools, by proper teachers, and sit proper exams that, if passed, will give them recognised qualifications that will help them to progress in the world. Yet during the eighteenth century, the only schooling that the sons and daughters of non-commissioned officers would have received was in cursing and fending for themselves and, if they were girls, making themselves useful by washing and sewing for their father's soldier comrades. Although regimental schools were increasingly being established, with senior non-commissioned officers initially doing the teaching, these were originally intended to teach illiterate recruits how to read, write and calculate. But then because many of those illiterate recruits were army children, the realisation dawned that the regimental schools might as well start teaching these soldiers-in-the-making, and their future wives (for many army daughters later 'married into' the regiment) while they were still young. And occupying army children with schoolwork and needlework also had the advantage of keeping them out of trouble!

By the nineteenth century, regimental schools catering for army children and teaching a wide range of subjects (practical, as well as academic) were relatively commonplace, and in this respect, the army was ahead of its time. The regimental schools were replaced by garrison schools in 1887, and administrative changes have continued to be made in response to changing times, with the British Families Education Service (BFES) being set up to educate army children in Germany in the aftermath of World War II, for instance. Today, the schooling of army children abroad is provided by Service Children's Education (SCE), and when in Britain, army children attend local schools, that is, unless they are at boarding school.

Officers' children may always have received an education appropriate to their perceived status, but at the price of separation from their parents (often for years on end), for they were generally sent to a boarding establishment, be it a public school, a ladies' academy or a finishing school, in Britain. In addition, there were military boarding schools: the Royal Hibernian Military School (RHMS), established in 1769 in Dublin, Ireland, and the Royal Military Asylum (RMA), founded in 1801 in Chelsea, London, and today known as the Duke of York's Royal Military School in Dover, Kent. It has now been decades since all army children have been able to enjoy the (dubious) privilege of a boarding-school education, thanks to a continuity of education allowance (CEA), or boarding-school allowance (BSA), and subsidised flights to join their parents during the holidays. Indeed, the agonising decision as to whether to sacrifice family togetherness in favour of the undoubted benefits of stability and continuity of curricula during crucial pre-GCSE and A' level years is one that all peripatetic army families must continue to take.

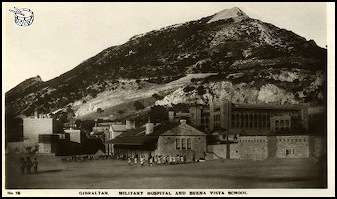

IN MEMORIAM: ART COCKERILL (1929–2016)

We were saddened to learn of the death, on 27 June 2016, of Art Cockerill, and thank his family for permission to reproduce Chris Crowcroft’s obituary of Art below.

'Soldier, hydro-electric pioneer, engineer, author, librettist, publisher and freelance contributor to Guardian Weekly, Arthur (Art) Cockerill has died at the age of eighty-seven in Cobourg, Ontario.

Born in Blidworth, Northamptonshire, Art was the fourth of ten children, all of whom feature in his novel Lay Gently on the Coals (Aesop Modern, 2011). As the son of a World War I regular soldier, Art entered the Duke of York’s Royal Military School in 1939. A proud “Dukie”, he went on to write the school’s bicentenary history, The Charity of Mars (Black Cat Press, 2002) and was a founder-member of its Clocktower Society. The school’s motto was the title of his history of boy soldiers, Sons of the Brave (Secker & Warburg, 1984). His fascination with military history led to the authorised biography of MI5 chief Sir Percy Sillitoe (W H Allen, 1975) and Winning the Radar War (with Jack Nissen, Robert Hale, 1989). A children’s book, Emma on Albert Street (Black Cat Press, 1997), was illustrated by Bill Slavin.

Commissioned into the Royal Engineers, he served post-war in Egypt. In 1957, he emigrated with his wife, Beryl, to Canada, where he worked as a hydro-electric engineer. His largest project was in Labrador, with lead investor Edmund de Rothschild. He also wrote the book for a musical, taking advice from George S Kaufman and Tyrone Guthrie – Art was never shy.

Leaving Quebec in the 1960s, he moved with his second wife, Charlotte, to Cobourg, Ontario, where he raised his family and pursued a successful engineering career that took him to Africa, the Caribbean and the Middle East. While working on airport installations in Libya, he had the opportunity to interview Gaddafi. He also spent time in custody. He established Delta Tech Systems, a technical publishing company that was “more lucrative”, he joked, “than any other publishing I undertook”. He championed social causes, ran for political office and played the clarinet in the Cobourg Kiltie Band, a skill learned at military school. Active to the end, he contributed and collaborated on many articles on military history and education to specialist historical reviews.

Art is survived by Charlotte, his wife of more than fifty years, and his children, John, Kate and Emma, as well as seven grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. His daughter Sarah predeceased him in 2001.

His energy, joie de vivre and uninhibited generosity to others means that he will not be forgotten.’

TACA echoes Chris’s closing words. A pioneering researcher, often with Peter Goble, into the history of army education, the Royal Hibernian Military School and, above all, the Duke of York’s Royal Military School – and more – Art was an enthusiastic and generous supporter of TACA ever since its establishment in 2007. Indeed, you will find evidence of Art’s erudition, and of his willingness to share his expertise, throughout the TACA website (see, for example, ‘PERSONAL STORY: KILLED IN ACTION’, ‘PICTURE: A REGIMENTAL SCHOOL IN INDIA’, ‘BACKGROUND INFORMATION: A SINGULAR AND MOST UNUSUAL SUB-POST OFFICE’, ‘TACA CORRESPONDENCE: BOY SOLDIERS AND EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY REGIMENTAL MUSTER ROLLS’, ‘TACA CORRESPONDENCE: MEMORIAL AT ALL SAINTS' CHURCH, HUTTON, BRENTWOOD, ESSEX’, ‘BOOK: A NEW HISTORY OF THE ROYAL HIBERNIAN MILITARY SCHOOL’ and ‘REVIEW: LAY GENTLY ON THE COALS’). As well as providing a window into his work, Art’s website, http://www.achart.ca, is a rich and important historical resource that will remain accessible to all for the foreseeable future. TACA is immensely indebted to Art, and sends sincere condolences to his family and friends.

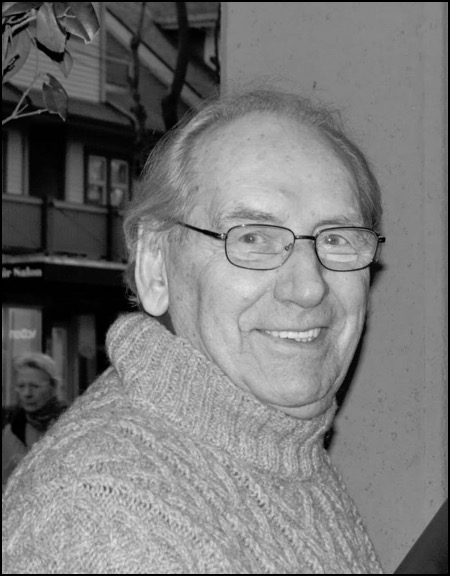

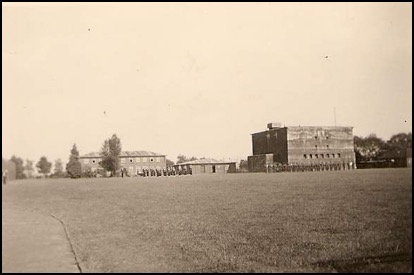

PICTURE: THE ROYAL HIBERNIAN MILITARY SCHOOL, DUBLIN, IRELAND

As the caption states, the photograph below shows the Royal Hibernian Military School in Dublin, Ireland, with its pupils lined up in front of it. Mounted on a postcard back, it was mailed in 1911 from Dublin to a recipient in Nottingham. In existence between 1769 and 1924, the Royal Hibernian School educated the orphaned sons of soldiers or those whose soldier–fathers’ absence overseas had left their families destitute. You can read more about the history of the school on the late Art Cockerill’s website: http://www.achart.ca.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: WERE TRADES TAUGHT TO ARMY CHILDREN IN THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY?

TACA has received the following message from Gay Fielding (née Campbell):

'My ancestor John Campbell enlisted in the 42nd Regiment in Glasgow in 1825, age 18 years, and his occupation was carpenter (WO 97). John was reportedly born and raised in army camps, according to his lawyer in his court case while he was still serving in 1845 in Nova Scotia. I have not yet been able to identify John's parents to determine whether his father was a soldier/officer of the British Army.

How would John have learned his trade if he and his mother and siblings (?) had been camp followers? Or would he have needed to have remained "at home" while his father was relocated to various theatres of duty? Any help you can give me would be appreciated.'

If you have any information that you think will help Gay, she can be contacted at the following e-mail address: gayze@tpg.com.au.

ARMY SCHOOLMISTRESSES IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES

Howard R Clarke is the author of A New History of the Royal Hibernian Military School, 2011. In this illuminating article, Howard traces the history of the army schoolmistresses, an intrepid band of women who taught soldiers’ children wherever they were posted in the world. TACA is grateful to Howard, and to Art Cockerill, for permission to publish this piece, which appears on the Delta Tech Systems website, as do the memoirs of Dorothy Bottle, who is mentioned at the end.

‘The first schoolmistresses who were publicly funded to teach soldiers’ daughters were those employed at the Hibernian School and the Royal Military Asylum, but the origins of army schoolmistresses must be traced back to the system of regimental schools. Although a number of commanding officers (COs) had established schools supported from regimental funds, and had received encouragement from the Duke of York following the policy of enlisting boy soldiers in 1796, it was not until 1812 that the order was given that all battalions and corps should establish regimental schools under the direction of sergeant schoolmasters. The various circulars and orders made it clear that the aim was both to educate young soldiers and attested boys and also soldiers’ children – so that their fathers would know that the state was concerned about their welfare. Hence, from 1812, the regimental schools were open to both the sons and daughters of soldiers, and all were taught to read and write and were given some basic arithmetic tuition by the sergeant schoolmasters. Commanding officers were also encouraged to employ the “best qualified and best behaved women of each Regiment” to instruct the girls in “Plain Work and Knitting”. This was the regime that continued until 1840, and king’s regulations continued to encourage commanding officers to employ soldiers’ wives of good character to instruct the girls in useful domestic skills.

In 1840, there were about 10,000 girls accompanying battalions and corps, or at their depots (this number does not include the artillery or the sappers), and a return compiled by the War Office for the year to 1 January 1837 recorded that there were, on average, 46 boys, 47 girls and 14 adults at each of the schools of the cavalry regiments, and an average 47 boys, 41 girls and 44 adults at the regimental schools of the infantry. In 1840, at the suggestion of Lieutenant-Colonel Somerset, the CO of the Cape Mounted Rifles, the War Office agreed to the appointment of a paid schoolmistress to each infantry battalion and cavalry regiment, and at each infantry depot. Following parliamentary approval, this was effected in a Royal Warrant issued on 29 October 1840, which specified that the schoolmistress should be qualified “to instruct the Female Children of Our Soldiers as well as in reading, writing and the rudiments of arithmetic, as in needlework and other parts of housewifery, and to train them in habits of diligence, honesty and piety”. A circular in November 1840 advised COs to give “careful attention to the morals and habits of the incumbents” and suggested that there were likely to be qualified persons amongst the wives of non-commissioned officers (NCOs). It was left to COs to select suitable persons and make the appointments, and it would be necessary to consult the muster rolls of the units on the Army List to establish how many army schoolmistresses were appointed during the 1840s and 1850s.

In 1850, a Royal Warrant established infant schools, “of which the Schoolmistress shall have the sole charge”, at which both sexes were instructed in reading and writing until they were sufficiently advanced to receive instruction from the trained army schoolmaster in the children’s school. The army schools were therefore co-educational, with the exception of the Royal Artillery schools at Woolwich (and subsequently at the garrison schools at Chatham and in Gibraltar), which had separate boys’ and girls’ schools. The warrant also established industrial schools under the schoolmistress to teach the girls knitting, needlework and household occupations. These were not separate establishments, but merely the name given to the afternoon activities at the children’s schools. (Boys could also attend an industrial school.)

CERTIFICATES OF MORAL CHARACTER REQUIRED

From 1858, female candidates for appointment as army schoolmistresses who did not possess qualified-teacher status were sent at public expense to one of a designated list of teacher-training establishments in Great Britain or Ireland. They had to be between eighteen and thirty-three years of age and to have a certificate of moral character from a clergyman of their religious denomination. There was an expectation that an army schoolmistress would be qualified to teach reading, writing and arithmetic, geography and religious studies, and that she should be a good needlewoman, competent in dressmaking and knitting. She was also expected to possess a taste and ear for music, especially singing. All for around £20 per annum!

It was hardly surprising that Army Inspector Lefroy, in his 1859 inspection, reported that it was difficult to obtain a supply of trained schoolmistresses for regiments. There were plenty of wives and daughters of NCOs who applied for training, but despite having the requisite personal qualities, they had had a poor education. If the schoolmistresses were married, they moved with their husbands, and not to where there were vacancies, and, if they were unmarried, “their employment is restricted by considerations of prudence”. Successive reports dwelt on the difficulties of accommodating single women teachers in barracks.

In 1863, regulations improved the pay and system of appointing schoolmistresses. Pupil-teachers (monitresses) could be appointed, and a new class of assistant schoolmistress was established, with selections being made from NCOs’ wives to assist on the same pay and conditions as pupil-teachers. In 1865, there were 443 female teachers, including 209 trained army schoolmistresses, and the Council of Military Education reported that these were well-qualified and committed to their work. The 1872–73 Inspector’s Report listed 238 trained and qualified schoolmistresses in charge of the infant and industrial schools, 55 acting schoolmistresses (who had passed the army’s entrance examination), 66 pupil-teachers and 336 monitresses.

It was difficult to recruit sufficient trained teachers as army schoolmistresses, partly because the pay was not sufficiently attractive and promotion prospects were better in civilian schools. Army schoolmistresses were also required to serve away from home for frequent long periods of foreign service in India and the colonies. Mothers were also concerned for their daughters’ morals if they wished to join a regiment as a schoolmistress.

TWENTIETH-CENTURY ARMY SCHOOLMISTRESSES

By 1914, candidates for the position of army schoolmistress had to be between twenty and twenty-two years of age; to satisfy appropriate physical and educational standards; and to undergo a course of twelve months’ training at Aldershot. They were not permitted to marry a soldier below the rank of sergeant, and became liable for retirement on marriage, but this was not always enforced. Although schoolmistresses were administered with the Corps of Army Schoolmasters, they had an independent existence as far as pay and conditions of service were concerned. They were neither civilians nor military, and suffered the disadvantages of both. They were governed by War Office regulations, and could be directed to serve at any army school at home or abroad. Yet they were not a recognised army unit, had no uniform, and their pay was not raised in line with army pay; in 1919, they were paid about the same as a lance corporal.

The Royal Warrant establishing the Army Educational Corps in June 1920 stated that, “Army Schoolmistresses shall bear the same relationship to our Army Educational Corps as they bore to our Corps of Army Schoolmasters”. Their rates of pay and conditions of service were to be laid down in warrants and issued in army orders. This 1920 warrant for the pay and conditions of army schoolmistresses paid them less than civilian teachers, which was a cause of grievance among the 289 serving schoolmistresses, and adversely affected recruitment.

The army schoolmistresses were designated Queen’s Army Schoolmistresses (QAS) from 1927, but none were recruited during World War II, and their numbers had halved to 154 in March 1946. The army children’s schools in the UK were handed over to the local education authorities (LEAs) in 1946, and thereafter male and female qualified teachers were invited to apply for three-year secondments from the LEAs to serve as civilians in army children’s schools overseas. In consequence, the number of serving QAS declined to thirty in 1957, and by 1970, only one remained.

MISS DOROTHY MABEL BOTTLE: A QUEEN’S ARMY SCHOOLMISTRESS

Little is known of the life of Miss Dorothy Mabel Bottle (c.1886–1973), the author of a memoir entitled Reminiscences of a Queen’s Army Schoolmistress, beyond her experience as an army schoolteacher. It is known from John Bottle, Dorothy Bottle’s nephew, that his aunt was born in Yorkshire and retired there after a full life of teaching from 1904 until 1935. She taught in military schools in Ireland, Jamaica, Egypt and the garrisons of home command, and travelled extensively in the Middle East. A keen observer and articulate reporter of army life and the communities in which she spent her teaching career, be it in home service or foreign stations, she maintained a lively awareness of the world in which she lived and worked. She was a non-judgmental reporter of the politics of her day, whether mixing with supporters of Sinn Féin during her time in Ireland at the turn of the twentieth century, or discussing the customs of her native England or the Arab–Jewish conflict. Her narrative makes most interesting reading [click here to read it].’

© Howard R Clarke, September 2010.

PICTURE: AN ARMY SCHOOLMASTER AND ARMY SCHOOLMISTRESSES, DEEPCUT BARRACKS, SURREY, C.1910

Scribbled on the back of the photographic postcard shown below are the words, ‘Wives/Instructors Deepcut Barracks c.1910’. The man at the centre of the group wears an army schoolmaster’s uniform, while the books with which many of the women are pictured suggest that they are army schoolmistresses. Howard R Clarke’s brief history of the women who taught army children, ‘ARMY SCHOOLMISTRESSES IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES’, appears above.

THE CALEY: THE ROYAL CALEDONIAN SCHOOLS AND THE ROYAL CALEDONIAN SCHOOLS TRUST

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: DID YOUR ARMY-CHILD ANCESTOR ATTEND THE GARRISON SCHOOL AT RICHMOND BARRACKS, DUBLIN, IRELAND?

When contributing a photograph of army-child Martha Tuckwell’s gravestone to TACA (see below), Catherine Neville, of the Richmond Barracks Exhibition Centre in Dublin, Ireland, explained that Richmond Barracks was a former British Army barracks. She continued:

‘We would like to enhance our school tours to provide visiting children with an insight into school life for garrison children. I am therefore currently researching the garrison school, and would be grateful if anyone could provide any information on family members who may have attended the school between 1857 and 1922.’

If you have any information for Catherine, please contact TACA, and we’ll pass it on. And for more on Richmond Barracks and its history, visit its website: http://www.richmondbarracks.ie.

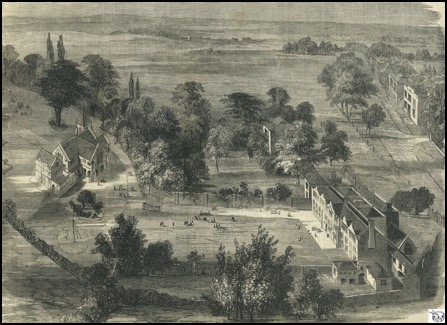

PICTURE: THE SOLDIERS’ DAUGHTERS’ HOME, HAMPSTEAD, 1858

The print reproduced below, which has been slightly cropped, shows the Soldiers’ Daughters’ Home in Hampstead, and was published on 19 June 1858 in The Illustrated London News to mark the opening of the institution’s new buildings (‘most pleasantly situated in their own grounds’) the previous day by Prince Albert.

‘It is the only asylum in the kingdom for the daughters of the Army; and, as a proof of the broad scope which its operations embrace, it may be mentioned that the last child admitted was a total orphan of the 56th Infantry, sent direct from Hong-Kong to the Home. Its object is to provide for these children, whether orphans or not, a permanent home, where they are maintained, clothed, educated, and trained industrially. The children in the Home are admitted at the earliest age, preference being given, first––to total orphans; secondly––to motherless children; thirdly––to fatherless children, &c; and it is a part of its plan to continue a supervision over the girls after they have entered upon the duties of active life, and to afford a temporary home for them when from no moral fault they are unable to obtain a situation. Two girls have been sent out, and are fulfilling the best expectations of the committee. There are now 130 children in a temporary home closely adjacent; the average has for a long time been 120, and it may be stated, as a proof of the salubrity of the situation and the watchful care of the committee, that no illness has existed in the Home beyond the casual complaints to which children are liable.’

(For another picture, and a little information about the history of the school, later known as the Royal Soldiers’ Daughters’ Home and then the Royal School, see below, ‘PICTURE: THE ROYAL SOLDIERS' DAUGHTERS' HOME, HAMPSTEAD’. In 2012, the Royal School was integrated into North Bridge House School.

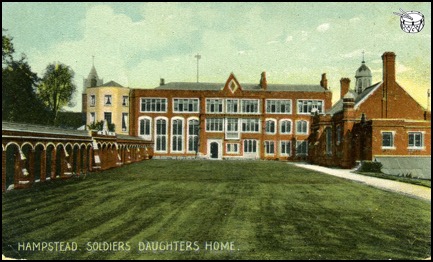

PICTURE: THE ROYAL SOLDIERS' DAUGHTERS' HOME, HAMPSTEAD

The Royal Soldiers' Daughters' Home, pictured below in an old postcard, was established at Rosslyn House, Hampstead, London, in 1855, 'to nurse, board, clothe and educate the female children, orphans or not, of soldiers in Her Majesty's Army killed in the Crimean War', the original aim being to equip them to earn a living either in domestic service or as regimental schoolmistresses. Situated at Vane House from 1858 (see above, ‘PICTURE: THE SOLDIERS’ DAUGHTERS’ HOME, HAMPSTEAD, 1858’), the school subsequently accommodated up to two hundred of the daughters of serving and retired soldiers, and not just the destitute, the girls being aged from infancy to sixteen. Later an independent school renamed the Royal School, Hampstead, this was integrated into North Bridge House School in 2012.

PICTURES: THE ROYAL SCHOOL, BATH, SOMERSET

The text along the bottom of the black-and-white postcard below tells us that the building pictured is in Bath: ‘The School for Officers’ Daughters’. The postcard below that shows a view of the ‘Courtyard Steps, Memorial Wing’.

The Royal School opened in Bath, Somerset, in 1865, its proposed objective being ‘to bestow upon the Daughters of necessitous Officers of the Army, at the lowest possible cost, a good virtuous and religious Education, in conformity with the principles and doctrines of the Church of England’. Having merged with Bath High School in 1998, it is today known as the Royal High School. Click here to visit its website.

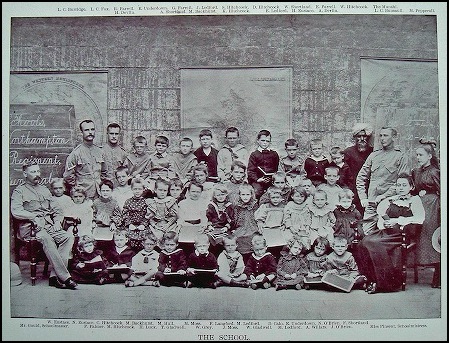

PICTURE: A REGIMENTAL SCHOOL IN INDIA

The photograph below, which was kindly contributed by A W (Art) Cockerill, shows the regimental school of the 1st Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment (previously the 48th Foot) in India, probably in Secunderabad, in around 1889–90. As Art writes, 'Well before the end of the nineteenth century, every unit serving overseas – and some in the home and Irish commands – was well served with one or more teachers that might include a schoolmaster sergeant, a schoolmistress and an assistant. Some units, such as the 48th Foot in an Indian station shown here, were exceptionally well provided for. In this instance, a total of seven teachers, assistant teachers and helpers, including a munshi ('teacher' in Urdu, believed to be a linguist who taught the children and adults Urdu), attended to a class of 37 children. This was an exceptionally high teacher–pupil ratio.' Art also points out the 'uniformed boy third from the right, back row, who I am convinced is a boy soldier of the regiment. He might be 14 at a stretch'. The school's munshi is standing next to this older boy, while the schoolmaster and schoolmistress are seated in chairs flanking their young charges. Perhaps unusually, everyone in this photograph, including each child, is named, from which it appears that a number of the children are siblings.

'A CONCERT BY SOLDIERS' CHILDREN IS FREQUENTLY A TREAT': CHILDREN OF THE REGIMENT IN 1896

As 'Red Cross', the author of 'Tommy Atkins Married' – an article that first appeared in the 18 September 1896 issue of The Navy and Army Illustrated – indicates in the extract reproduced below, the curriculum taught at army schools during the late nineteenth century reflected contemporary British values. Music, it seems, was particularly thoroughly and effectively covered. (For the cheerful picture painted by Red Cross of the 'children of the regiment', click here; here for an indication of how they were fed; and here for a description of their accommodation.)

'Soldiers' children, amongst their other advantages, have the benefit of excellent schools. Here they are given a thoroughly sound English education, the girls in addition being well grounded in needlework, darning, etc. Music, both theory and practice, is taught and well taught, and a concert by soldiers' children is frequently a treat worth going some distance to enjoy.

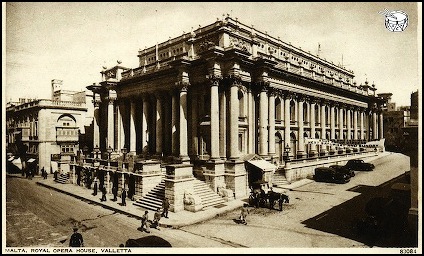

I had the pleasure about two years ago of being present at a concert given in the Royal Opera House in Malta, by the combined schools of the Garrison. Upwards of three hundred children took part, and no prettier sight have I ever witnessed than the appearance on the stage of these little ones. The programme consisted of solos, part songs, and glees, interspersed with fan drill and other beautiful movements, the whole of which was admirably executed.'

Above: The grand Royal Opera House in Valletta, Malta, where the children of the garrison performed before 'Red Cross', was constructed in 1866.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: INFORMATION SOUGHT ABOUT GREEN HILL SCHOOLS, WOOLWICH, SOUTH-EAST LONDON

TACA has received the following request for information:

‘Researchers in the Royal Borough of Greenwich are keen to find out about the local army school at Woolwich known as Green Hill Schools. It is believed that the school taught local army children up until the 1960s, but there is a lack of information about it, so we would love to hear from anyone with memories of being taught (or teaching) there.’

If you can help, please contact Carolyn Ayres, Heritage Project Officer of the Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust; her e-mail address is: Carolyn@rght.org.uk.

English Heritage's Survey of London, 2012, includes some information about Green Hill Schools’ history. To read it, click here and scroll down to pages 62–64.

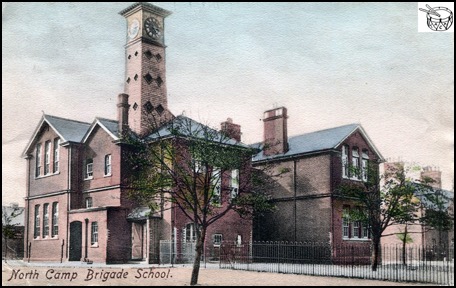

PICTURES: NORTH CAMP BRIGADE SCHOOL, FARNBOROUGH, HAMPSHIRE, 1905

This colour postcard, which was first published by Francis Frith & Co in 1905, presents a view of the North Camp Brigade School in Farnborough, Hampshire, named as such because it was part of Aldershot’s Northern Camp (the school was also known as the 1st Brigade Garrison School). Mailed on 31 May 1906, addressed to a Mr Fairley in West Bromwich, and signed ‘Percy’, the message concludes with the words, ‘This is a picture of my school’.

The partially tinted black-and-white postcard below was posted in 1904, and shows the ‘Brigade Schools, North Camp’ in Farnborough, Hampshire. A number of children, including a boy on a bike, can be seen on either side of the school’s railings.

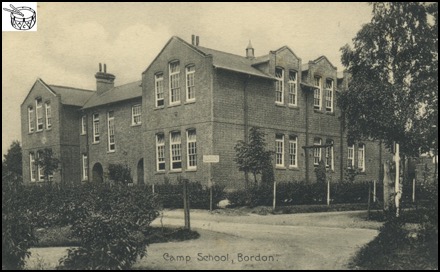

PICTURE: THE CAMP SCHOOL, BORDON, HAMPSHIRE

The building shown in the black-and-white postcard below, which dates from the early twentieth century, is the Camp School in Bordon, Hampshire. The words on the sign at the front of the building, in the centre of the postcard, are just discernible and read ‘LOUISBURG BARRACKS’. Constructed in Station Road in 1906 as a junior school, the school catered for infants from the late 1960s. Today, it houses Bordon’s Phoenix Theatre and Arts Centre.

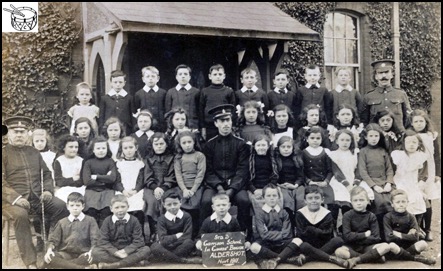

PICTURE: 'STD 3, GARRISON SCHOOL, 1ST GUARDS’ BRIGADE, ALDERSHOT', HAMPSHIRE, NOVEMBER 1911

The sign held by the boy sitting cross-legged at the centre of the photograph below reads ‘Std 3 / Garrison School / 1st Guards’ Brigade / Aldershot / November 1911.’. He and his classmates were photographed with three adults: a sergeant standing on the right (whose cap badge might be that of the Coldstream Guards, which were stationed in Aldershot in 1911), and two seated army schoolmasters, on the left and behind the sign-holding boy. The postcard was franked at Aldershot in November 1911. It was addressed in black ink to ‘Mrs King. / 137 Stewart Road / Bournemouth E / Hampshire.’. The message reads, ‘Guards / Aldershot / 27.11.11 / Dear M / This is one of the photos, I promised you. The other was a failure. I shall behaving [sic] one of the Company soon and will send that. Love to all, from / Yours Sincerely / Will’.

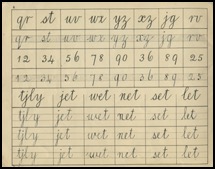

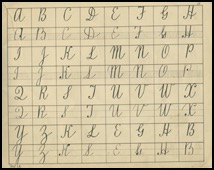

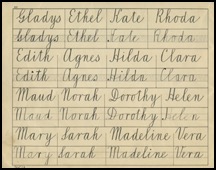

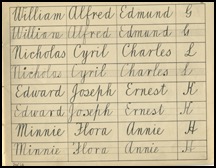

CONTRIBUTION: AN ARMY-SCHOOL COPYBOOK, 1914

We are most grateful to Brian Gillard, who generously contributed a boot-sale find to TACA, this treasure being an army-schools copybook dating from 1914. Copybooks were once used to teach children to write legibly, the idea being that they copied letters and words written by their teacher, or in a specimen book, into the book’s blank spaces. The information supplied, in pen and ink on the front and back of the book, tells us that it was completed by Harry Jones (who, as Brian observes, had ‘beautiful writing for an eight-year-old’), of the Line Wall Garrison Station army school in Gibraltar, as part of the Army Schools Annual Writing Competition, on 25 October 1914. As Brian says, it is ‘a great bit of army school history’, and TACA is delighted to have received it.

Above: The front cover of Harry Jones’ army-schools copybook shows the Horse Guards Building in London. The inclusion of Edward VII’s cypher indicates that the book was printed before the king’s death in 1910.

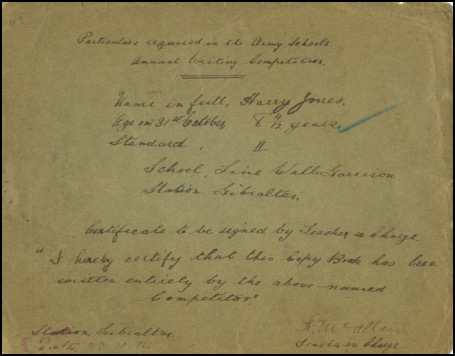

Above: The handwritten information given on the back cover reads as follows:

‘Particulars required in the Army Schools Annual Writing Competition.

Name in full, Harry Jones.

Age on 31st October, 8 4/12 years.

Standard, II.

School, Line Wall Garrison Station, Gibraltar.

Certificate to be signed by Teacher in Charge.

“I hereby certify that the Copy Book has been written entirely by the above-named Competitor.”

Station, Gibraltar – H.M. Allen

Date, 25.10.14 – Teacher in Charge.’

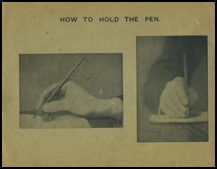

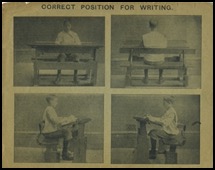

Above, left and right: Photographs printed on the inside covers demonstrate how to hold a pen (left) and how to sit correctly (right) when writing.

Above and below: Young Harry filled twenty-four pages with his penmanship: with letters, numerals, words and names; here are four pages from his copybook.

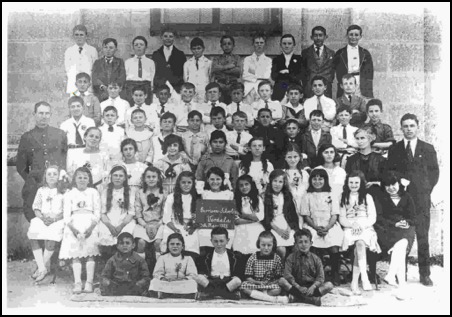

PICTURE: GARRISON SCHOOL, VERDALA, MALTA, 1921

The photograph that appears below, showing staff and pupils at the 'Garrison School, Verdala' in 1921, was generously contributed to TACA by Liz Mardel, who, in her accompanying message, explains how it came into her possession.

'I acquired the attached photo of the school for the children of soldiers in Verdala Army Barracks, Malta, dated as you see, 1921, in a strange way. As Miss McMeeking, I was a teacher at the Royal Naval School Verdala, situated nearby, from 1957 to 1961. When we were about to have our second reunion in 2005, I put a letter about it in the local Portsmouth News. A phone call then came from a woman in Gosport who had rescued a glass photographic plate from items sent to a Scout jumble sale and had been wondering who could find a good home for it! There is also a plate of the woman teacher in the fourth row from the top in the picture, so I suspect that the plates could have come from her family. The school was, I believe, in Cospicua, one of the two dual-purpose "chapel schools" on the island, but destroyed in World War II.'

For more on this photograph, see ‘TACA CORRESPONDENCE: AN AMAZING COINCIDENCE DISCOVERED IN ARMY CHILDHOOD’.

PICTURES: THE GARRISON CHILDREN’S SCHOOL, RIEHL, GERMANY, 1920S

The British Army occupied the Rhineland region of Germany during the 1920s, with the families of many of the soldiers posted there accompanying them on their tours of duty. (TACA’s ‘ON THE MOVE’ page carries a photograph of families arriving in Riehl, a suburb of Cologne/Köln in 1922, see ‘PICTURE: MILITARY FAMILIES ARRIVING IN RIEHL, GERMANY, 1922’.) Pictured below are some of the children and teachers of the Garrison Children’s School, British Army of the Rhine (BAOR), Riehl Area (the annotation has misspelled the German name, which is correctly given as ‘Riehl’ on the sign on the wall behind the children).

Reproduced below is a second, similar photograph (and ‘Riehl’ has again been misspelled on its label); it is striking how many of the girls are sporting oversized ribbons in their hair, while a number of the boys are wearing sailor suits.

PICTURE: THE GARRISON SCHOOL, ABBASSIA, CAIRO, EGYPT, IN 1928

The black-and-white photograph below was taken by K Bolam, of Cairo, and was printed as a postcard. A handwritten note on the back tells us that this is ‘a group of the whole school, infants and elder children’, the school in question being the ‘Garrison School, Abbassia, Cairo’, in Egypt, photographed in April 1928. Staff can also be spotted at the centre of the group of children.

PICTURE: THE ARMY SCHOOL, PORTSMOUTH, HAMPSHIRE

Judging by their clothing and hairstyles, this class of young army children attended the Army School in Portsmouth, Hampshire, some time between World War I and World War II.

PICTURE: ENTRANCE TO THE DUKE OF YORK’S ROYAL MILITARY SCHOOL, DOVER, KENT, 1930S

As the caption makes clear, this black-and-white postcard published by Valentine’s, which dates from the 1930s, shows the entrance to the Duke of York’s Royal Military School in Dover, Kent. A pupil (a ‘Dukie’) can be seen in the foreground. Founded in 1801 for the orphaned children of soldiers, the school was originally situated in Chelsea, but moved to Dover in 1909.

For more about the history of the Duke of York’s Royal Military School, visit the late Art Cockerill’s website: http://www.achart.ca. And click here to visit the school’s website.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: A SINGULAR AND MOST UNUSUAL SUB-POST OFFICE

‘At the height of its activities, before modern communications - e-mail, social networking and courier services - came into existence and greatly reduced mail services, the General Post Office (GPO), as the Post Office was called before 1969, had a post office in every town, village and hamlet throughout Great Britain. The sole exception among sub-post offices issued with identifying stamps to frank letters was the Duke of York’s Royal Military School.

The year in which the school received permission from the GPO to open a sub-post office is not known. (From the viewpoint of philatelic history, it would be useful to know this.) However, it is certain that a sub-post office was in existence at the school during the 1920s, and probably before that. It may even have been opened in 1909, the year in which the school moved from its old premises in Chelsea, London, to its spacious grounds on the white cliffs of Dover, in Kent, where freshening breezes from the English Channel provided the children with a healthy environment in which to grow.

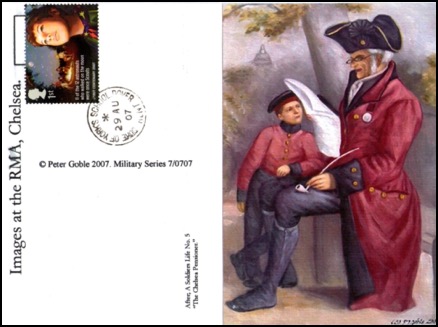

The Duke of York’s School’s franking stamp made a distinctive impression, as can be seen on Peter Goble’s Military series postcard below, by coincidence one of the last items of mail to be franked before the sub-post office closed in 2007. This postcard would be a rare and coveted stamp-collector’s item were it to be offered for sale on eBay or at a philately fair.

The photograph from the British Postal Museum & Archive (BPMA), reproduced here with the permission of the BPMA, was taken in 1938. The identities of the postmaster, a retired ex-soldier on the school staff who was required to wear his army uniform, and the young ‘Dukie’ at the wicket are both unknown.’

Art Cockerill.

Above: Sub-post office at the Duke of York’s Royal Military School, Dover, 1938. (© Royal Mail Group Ltd 2010, courtesy of The British Postal Museum & Archive.)

Below: A postcard franked with the postmark ‘Duke of York’s School Dover Kent 29 Au 07’. This is possibly the last franked piece of mail sent from the sub-post office at the Duke of York’s Royal Military School. The postmaster retired in August 2007.

Art Cockerill’s website, http://www.achart.ca, includes a comprehensive history of the Duke of York’s Royal Military School. Many thanks to Art for having contributed the above text to TACA; to Peter Goble, for permission to reproduce the postcard above; and to the British Postal Museum & Archive (BPMA), http://postalheritage.org.uk, for permission to reproduce the photograph above.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: IDENTIFYING AN ARMY RESIDENTIAL CO-EDUCATIONAL SCHOOL, 1930S

Family-history researcher Carole Temple has contacted TACA in her attempt to identify the army school that her grandfather’s children attended. Carole writes:

‘My grandfather, Albert Edwin Gould (1881–1929), served in the British Army for twenty years. He served in the East Surrey Regiment and the 15th Battalion (Scottish) Division, among other units. He was a private throughout his army service and was, I think, a garrison labourer.

After my grandfather died, his five youngest children were put into an army residential co-ed school in about 1931, until they reached, I think, sixteen years of age. I'm seeking the name of the school that they attended and any information about the school. Their names were Edward, James, Louie, and Gladys and Winifred (twins); their last name was Gould.’

We have suggested to Carole the Duke of York’s Royal Military School and the Royal Caledonian Schools as possible starting points, and if you think that you can help Carole further, please contact TACA and we’ll pass on your message.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: SEEKING PUPILS AT THE LAWRENCE MILITARY SCHOOL, MOUNT ABU, INDIA, 1940S

Richard Cordeux has contacted TACA regarding the Lawrence military schools in India:

‘Founded, by Major General Sir Henry Montgomery Lawrence, to provide education to the children of serving and deceased soldiers and officers of the then British Army in India, history has it that there were four Lawrence schools at the time of India’s Independence. The two oldest were started during Sir Henry’s lifetime. The oldest, at Sanawar, was founded in 1847; the second, at Mount Abu, was established in 1856. While the school at Sanawar is still going strong, the one at Mount Abu is no longer there: it became the Indian National Police Academy and now houses the Internal Security Academy.’

Richard attended the Lawrence school at Lovedale (the fourth was at Ghora Gali) in 1938, and that at Mount Abu from 1940 to 1945, and would like to make contact with old ALS (Abu Lawrence School) Mount Abu-ites. He can be contacted by e-mail at r.cordeux@btinternet.com.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: ‘DO YOU HAVE MEMORIES OF ATTENDING SCHOOLS IN LOVEDALE (INDIA), LAGOS (NIGERIA) AND CATTERICK CAMP (NORTH YORKSHIRE) WHEN MY FATHER AND I DID?’

TACA has received the following message from Margaret Charlton (née Richardson):

‘I am the daughter of Terence (Terry) Richardson, who was born and raised in Lovedale, southern India, the son of Major Albert Victor Richardson, schoolmaster at the Lawrence Memorial Royal Military School, Lovedale, Nilgiri. My late father had two brothers, Desmond and Brian. All three boys attended the Lawrence Memorial School, Lovedale, probably from 1934 until 1947/1948, when my father returned to the UK and was posted to Lisburn, Northern Ireland.

In 1954, we travelled from Lisburn to Lagos, Nigeria, where I attended a small school run by nuns. In 1957, we returned to the UK, to Catterick Camp, in North Yorkshire, where I attended the local army primary/junior school, which was sited on the crossroads with Hipswell village/Hipswell Road West and Richmond Road. The school was not far from Marne Barracks. Not far from the school was the local GP’s practice; at that time, the doctor was a Dr Connor. St Oswald’s Church was close by, as was the Brownie hut. I later left the garrison primary school and attended Hipswell Church of England Primary/Junior School, in Hipswell village, where the headmistress was a Mrs Slack. There were two other teachers, a Ms or Mrs Aitken, and a Miss Leftley (who later became Mrs Brown).

My quest is twofold. Does anyone recall my late father, or grandfather in Lovedale? Does anyone recall attending the small school in Lagos, or, indeed, the other that schools I have mentioned? If so, I would very much like to hear from you. Thank you.’

If you think that you can help Margaret, please contact TACA, and we’ll pass on your message.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: INFORMATION SOUGHT ABOUT THE BRITISH ARMY CHILDREN’S SCHOOL, MINGALADON, BURMA

Christopher Taylor has contacted TACA to ask if anyone has any photographs or information about a school for army children in Burma [now Myanmar] that he attended as an RAF child. Christopher writes:

‘Ours was the first family to join a serving officer in Burma; we arrived in 1946 aboard the SS Highland Princess. To begin with, I was taught by an English Buddhist monk. I started attending the British Army Children’s School at Mingaladon, in Burma, in 1947. The command education officer was S R Williams. Our badge was a red-blue-red square, with the Roman numerals XII under a chinthe, the mythical Burmese lion–dog.’

If you can help Christopher, please e-mail him at christophertaylor132@btinternet.com; TACA would also be interested to learn more about this school.

PERSONAL STORY: MY ARMY CHILDHOOD IN JERUSALEM AND CYPRUS

Robert Henderson’s father was serving in the Royal Signals when Robert was born at the start of of World War II. Here, Robert gives us an insight into his experiences of growing up in Jerusalem, Egypt and Cyprus during some exceptionally turbulent times.

‘Having been born in Jerusalem, Palestine, where my father was stationed, we moved to Egypt in 1941, when my father was posted there, and in 1942, when the German Army neared Egypt, we were evacuated back to Palestine. I stayed with my grandparents there, as my grandfather was on the high commissioner’s staff, having come there with General Allenby in 1918. My father was later wounded (and decorated) in North Africa. He was eventually moved to the BMH (British Military Hospital) in Palestine, and was sometimes brought to visit us by ambulance.

LIFE IN JERUSALEM

I went to school at the BCS (British Community School) in Jerusalem. The war was an inseparable part of our lives. No sweets, chocolate, or anything made in Britain or anywhere else. The Italian planes bombed ineffectually now and again. A blackout curfew was imposed, and shutters went on the windows. The Free French came in, and the officers’ families joined married quarters. A good friend was a French boy, Totty, and I picked up some French, which I still have. Later, the Polish Army came in, but I never met a Polish boy.

On the king’s birthday there was always a parade at the high commissioner’s place: the Black Watch marched with a massive pig mascot and bagpipes, and Spitfires flew above. We knew the British Army was unbeatable – none to compare with it – and after midday, and cod-liver oil at school, one was allowed to slide down two stories of banisters roaring out “Some talk of Alexander, and some of Hercules Of Hector and Lysander, and such great names as these. But of all the world’s great heroes, there’s none that can compare. With a tow, row, row, row, row, row, to the British Grenadiers”. At all other times, sliding on the banisters was a punishable offence.

We children were spoiled by the army men, who would do all they could for us. Also, being taken by my grandfather for lime juice at the officers’ club was a great treat. I can still almost smell the Player’s Navy Cut smoke, the whisky and the beer aroma, and there was often singing around the piano. Chips and lime juice on the bar among the uniformed heroes – happy days.

There were memorial services for the fallen at Sunday church parades, when the padre would read out names of relatives. Every evening at six o’clock, we would wait near the radio to hear: “London calling, London calling. This is London calling, and here is the news . . . “. My grandfather would take notes, and afterwards we would move the pins on the large world map fixed to the wall: silver-headed pins for the British, green for the Americans, red for the Russians, black for the Germans, yellow for the Japanese. I learned a lot of geography this way. My grandfather told me we would win the war, and he was right. Of course, I knew we would. The sun never set on the British Empire and the map of the world was largely pink. QED.

We were British, the best of the best, and pity those who were not. We lived in a sort of bubble, and though I saw local children, I never spoke to one. Unthinkable in present-day terms.

Winston Churchill and King George were our heroes. By strange chance, King George markedly resembled my father (or should it be the other way around?) and this was particularly endearing.

We were all Beano and Dandy fans, and long discussions and arguments went on at school about the contents of these comics. Desperate Dan, Keyhole Kate and so on were real people to us, as were the brave British soldiers and the evil Huns in the comics. The comic books themselves were rare, and whoever had one was courted. We also read non-war subjects, and the Just William books were my all-time favourites. Dinky Toys were highly prized, especially the military models.

And then, finally, one glorious spring day in 1945, V-day [Victory-day]. We had won (naturally). Now there were unshuttered lighted windows at night, and no more rationing. Australian cheese and butter, Marmite, Worcestershire sauce, HP sauce, ketchup, relish, chocolate etc, etc – all the things we spoke about and had rarely had before.

Everyone talked about going “home”. Fabled Trafalgar Square and the legendary delights of Brighton and Blackpool beckoned, but we stayed on, as my grandmother went into missionary work for the LSCJ (The London Society for the Conversion of the Jews).

EVACUATION TO CYPRUS

Then the troubles started with the Arabs and the Israelis, and in November 1947 we were warned for Operation Polly, whereupon we packed and were evacuated to Cyprus. This was my second evacuation.

We were told we would return when the troubles were over, but this never happened. Instead, my father went into the BMH in Cyprus and I was enrolled at the army children’s school in Nicosia, first in the junior class and then in the intermediate class, until 1951, at which time we finally went “home”.

Here are a few of the names I can recall from my schooldays in Cyprus: Jack (Jackie) Dean, Elizabeth (Lizzy) Dean, Alexandra (Sandra) Marshall and Caroline White. I would be glad to hear from them and any other army children who were at the BCS Jerusalem or the army children’s school in Nicosia when I was. I can be contacted at bob10@012.net.il.'

Robert Henderson (b.1939)

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: INFORMATION SOUGHT ON ARMY SCHOOLS IN AUSTRIA

William Dickins attended British army schools in Graz, Vienna, Klagenfurt and Villach (all in Austria) after World War II, and has contacted TACA for advice on finding out more about them. If you can help him, or can recommend a useful source of information on British service schools in general in Austria during the post-war period, please e-mail TACA.

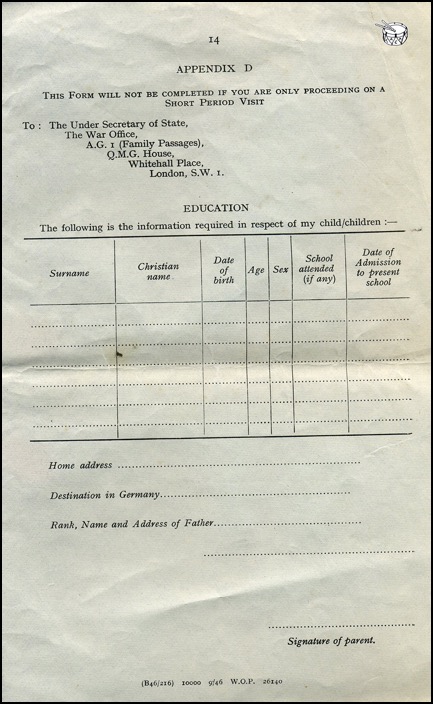

GUIDE TO FAMILIES PROCEEDING TO B.A.O.R., AUGUST 1946: EDUCATION

Just over a year after the end of World War II, many army families were preparing to join their soldier husbands and fathers on accompanied postings to the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR). Before they set off, the War Office provided them with a briefing booklet entitled Guide to Families Proceeding to B.A.O.R. (publication date: August 1946), covering such issues as travel arrangements and medical matters. Army children’s education was also addressed, as follows.

‘Education in B.A.O.R.

22. In order to assist the Director of Education, B.A.O.R., to arrange for the provision of educational facilities on the continent, you are asked to complete the form at Appendix D and to send it to the War Office as soon as possible. You need NOT send in the form if you are only going on a short term visit.’

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: BAOR SECONDARY SCHOOLS AND SPECIAL TRAINS

Peter Watson, a former army child who attended King Alfred School, in the northern German town of Plön, in Schleswig-Holstein, between 1953 and 1957, outlines the history of the secondary schools that were set up for the children of service personnel who were posted to British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) locations after 1945, as well as the special trains that transported them there. See 'Links', below, for more about these schools.

'It was a Cabinet-level decision by the 1945 British Labour government that before their families could join the entitled servicemen and certain military-sponsored civilians in the British Zone of Germany (OP UNION), plans for an education system equivalent to the standards available to all in Britain, irrespective of service, rank or status, had to be in place. Questions were subsequently raised by MPs in the House of Commons seeking confirmation that the schools would be open to all, irrespective of rank or service, and that no special privileges would be given to officers' children.

The provision of primary education was relatively easily solved by the establishment of small schools in all of the large garrisons and individual, more isolated, major units. The problem of secondary education (for children above the age of 11) was more complex, with 1,000 potential pupils being scattered over an area the size of Wales. A co-educational, comprehensive boarding system was the only sensible solution, although this was totally alien to the majority of the parents and children, as well as the staff.

Prince Rupert School (PRS), Wilhelmshaven [in Lower Saxony, north-western Germany], opened with 70 pupils for a one-month trial in July 1947, in the naval barracks attached to the former Kriegsmarine dockyard. The experiment was judged a success, and 250 pupils joined for the autumn term. King Alfred School (KAS), Plön, was to follow in the summer of 1948, initially with 500 pupils, and subsequently with 600. There were also small secondary day schools in Hamburg and Berlin for a time, but these were not viable and closed in the early 1950s, the pupils being transferred to KAS and PRS. The provision of boarding-school places peaked in 1953, with the opening of Windsor School, Hamm [in North Rhine-Westphalia, north-western Germany].

However, the subsequent restructuring of BAOR and RAF (Germany) into the British elements of the new NATO force based in West Germany, the reduction of troop numbers and increasing infrastructural costs meant that the existing system had to be radically revised. King Alfred School, Plön, closed in the autumn of 1959, and Windsor School, Hamm, was divided into two separate schools. Queen's School, Rheindahlen [in North-Rhine Westphalia], had opened in 1955 to provide day secondary-school facilities for the children living in the new NATO headquarters and adjacent British garrisons and RAF stations in the lower Rhineland. Day secondary schools were opened in other major garrisons where there was sufficient demand, although the more academic pupils (with the exception of those living in the Rheindahlen area) were required to board at PRS or the Windsor schools.

PRS in Wilhelmshaven closed in 1972, but its name and traditions were transferred to a new day school adjacent to the then British military hospital (BMH) in Rinteln [also in Lower Saxony]. The Windsor schools in Hamm closed in 1983, but a small, replacement, boarding facility for the more academic pupils was created at Kent School, Hostert. There was a further rationalisation in the Rheindahlen area in 1987, following which both Kent School, Hostert, and Queen's School, Rheindahlen, closed and a new Windsor School opened on the latter site with enhanced facilities, including a small boarding annexe.

SUMMARY OF BRITISH FAMILIES EDUCATION SERVICE (BFES) SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN BAOR

The boarding schools were:

- Prince Rupert School, Wilhelmshaven, 1947-72;

- King Alfred School, Plön, 1948-59;

- Windsor schools, Hamm, 1953-83.

The day schools included (details are incomplete):

- (?) in Berlin, 1947-50, and early 1970s to 1992; [see 'TACA CORRESPONDENCE: THE HAVEL SCHOOL, BERLIN, (WEST) GERMANY', below]

- (?) in Hamburg, 1947-52 (?); [see 'TACA CORRESPONDENCE: THE BRITISH SCHOOL HAMBURG, (WEST) GERMANY', below]

- Queen's School, Rheindahlen, 1955-87;

- Cornwall School, Dortmund, mid-1960s;

- Heide School, Hohne, 1960s onwards;

- Kent School, Hostert, 1960s to 1987;

- King's School, Sundern, 1960s onwards;

- (?) in Münster, mid-1960s; [see 'TACA CORRESPONDENCE: EDINBURGH SCHOOL, MÜNSTER, GERMANY’, below]

- Lancaster School (?), Osnabrück, mid-1960s to 2008;

- Prince Rupert School, Rinteln, 1972 onwards;

- Windsor School, Rheindahlen, 1987 onwards.

THE SCHOOL TRAINS

Rail was the preferred method of long-distance travel within the British Zone, and as part of this policy, special trains to and from Wilhelmshaven, where Prince Rupert School (PRS) was located, and Plön, the home of King Alfred School (KAS), ran at the beginning and end of each term. One train for each school was initially sufficient, but by 1950, following an increase in pupil numbers, two trains were required for each school.

For PRS, Wilhelmshaven, the basic routes from 1947 to 1972 were as follows.

- A Train: Krefeld-the Ruhr-Münster-Osnabrück-Bremen-Wilhelmshaven;

- B Train: Bielefeld-Wunsdorf (where the through section from Hannover/Celle was coupled on)-Bremen-Wilhelmshaven.

For KAS, Plön, the basic routes were as follows. [See 'ON THE MOVE'/'PICTURES: KING ALFRED SCHOOL (KAS) TRAINS'.]

- A Train: Köln-the Ruhr-Hamm-Münster-Osnabrück-Bremen-Hamburg-Lübeck-Plön;

- B Train: Gütersloh-Bielefeld-Hannover-Hamburg-Lübeck-Plön.

The trains stopped in all of the major British garrisons en route to pick up or set down passengers, some of whom would have to travel by road to their final destinations. Pupils travelling to and from Berlin would change at Hannover (Hanover) to join the overnight "Berliner", the British military train.

It is believed that no special trains were provided for pupils from the Windsor schools at Hamm. They would use the existing troop trains (which stopped in Hamm), travel by civilian train or be bussed to and from their home garrisons, which were generally in the south of the British Zone. Those pupils living in Berlin used the "Berliner" for that part of their journey between Berlin and Braunschweig (Brunswick).'

Peter Watson.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: THE HAVEL SCHOOL, BERLIN, (WEST) GERMANY

Thanks to Jens Dunne, who has been in touch concerning the missing name of the day school in Berlin attended by army children from the early 1970s to 1992 that is listed in the item headed 'BACKGROUND INFORMATION: BAOR SECONDARY SCHOOLS AND SPECIAL TRAINS', above. According to Jens (who was a student there), this was the Havel School, and its premises are now an RAF base.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: THE BRITISH SCHOOL HAMBURG, (WEST) GERMANY

On New Year's Day in 1947, Jeanne Dawson (or Brookwick, as she was then) set sail with her mother and brothers from Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, for (West) Germany, to join her Canadian father, who was working with the Control Commission Germany (CCG) in Hamburg. In 2010, a visit to TACA's 'SCHOOLING' page prompted Jeanne to send the following message. If anyone who went to the British School Hamburg during the late 1940s remembers Jeanne, 'the Canadian girl', she would love to hear from them, and can be contacted through TACA.

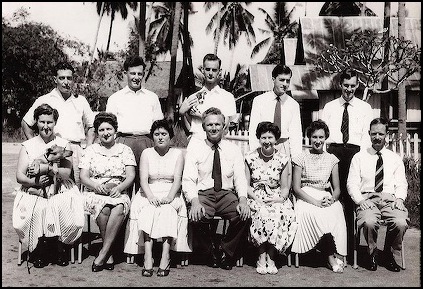

'Just for nostalgia's sake, I looked up my old school in Hamburg, Germany, which I attended from 1947 to 1949, and couldn't believe that it wasn't recorded [in the "BACKGROUND INFORMATION: BAOR SECONDARY SCHOOLS AND SPECIAL TRAINS" item, above] except as "(?) in Hamburg". It was situated just outside Hamburg in Altona, and I still remember the names of the headmaster and some teachers. The pupils' ages ranged from infants to sixth form.

The picture below, of the whole school's children and staff on the steps of the building, was taken in 1949, I believe. I don't see any infants in the photograph, the youngest appearing to be eight or nine. Whether their picture was taken on another day, or they were schooled elsewhere, I can't think. The two statues on either side of the group were of Martin Luther and Copernicus ("copper knickers" to the younger boys!) I am in the back row, fourth from the left in a white top. The staff as pictured from left to right are: a language teacher, I believe; Mrs Walker (who taught religious education, or RE); Miss Paterson (sport): Mr Uhren (sport); Miss Murray (French); P J T Morrill (the headmaster); Bob Christie (English and, I think, history); Miss Buchan (maths); Mr Woolley (languages); unknown; Mr Preece (geography); and Mr Conway (art). Another teacher whose name I remember, but who is not shown here, was Miss Cooper (science).

At some point early on in the period that I was there, we were told – in assembly – the new name of the school, which was to be christened "British School Hamburg". I can still remember the collective groan that went up at such an unimaginative name, compared to the ones at Wilhelmshaven and Plön. I'm a bit of a hoarder, paperwise, but apart from my original passport (from which I see that we came to England from Germany in December 1949), I have no documentation from my schooldays. I can't help wondering whether, had the school had been named something historic like "Prince Rupert" or "King Alfred", as with the schools in Wilhelmshaven and Plön, its identity would have survived rather better in the records. I only hope that someone somewhere who attended the school and looks up TACA will get some pleasure from the photograph.'

Jeanne Dawson (née Brookwick, b.1932).

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: EDINBURGH SCHOOL, MÜNSTER, GERMANY

Thanks to both Ann Lucas-Nemer and Amanda Sedgwick for supplying the missing name of the secondary day school in Münster – Edinburgh School – listed in Peter Watson's outline of the BAOR secondary schools and special trains in Germany after 1945, above. Amanda adds that the school has since closed, and that she believes that the premises are being used by the Dutch military.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: BFES PRIMARY SCHOOL AT STADE, (WEST) GERMANY

TACA has received the following message from Elaine Hart, prompted by the missing name of the secondary day school in Hamburg that Peter Watson touched on in his piece above (see 'BACKGROUND INFORMATION: BAOR SECONDARY SCHOOLS AND SPECIAL TRAINS').

'I see that the information listed on this website is incomplete for the BFES day school in this area. There was a school at Stade and I attended it between c.1949 and 1951 (between the ages of 7 and 9). It was for children aged up to 11 – after that, children boarded at Wilhelmshaven. There were two classes – one for infants and the other for the junior age group. I think the whole school roll numbered fewer than a dozen children. I seem to remember the number 15 being mentioned, but I can't remember all of them. We lived first in Stade, but then moved into married quarters at Hesedorf and travelled an hour each way to school, in all weathers, even the tiny children. Service children have to be tough! I hope this information will be useful to you. My purpose in accessing this site was because I am trying to find the name of our teacher there. She was marvellous. Scottish, I think – perhaps from Inverness, and she gave us such a good grounding in the 3Rs despite having such a wide range of ages and abilities to deal with. The infants were taught by a German teacher, I think. If you can suggest any other sources of information to enable me to find her name, I would be grateful. Perhaps there are lists published of those who served in the BFES in those days in BAOR?'

Elaine (whose father was in the RAF, based at RAF Hesedorf, near Bremervörde, when she attended this school) also writes that she and her sister Margaret managed to locate their old school in Stade on a visit to Germany in 2005. If you can help Elaine in her quest to learn her teacher's name, please contact TACA.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: ‘WE WERE PRIMARY-SCHOOL PUPILS IN STADE, (WEST) GERMANY, C.1950’

On reading Elaine Hart’s above message about the BFES primary school at Stade that she attended in (West) Germany between around 1949 and 1951, David and Valerie Wells contacted TACA with the following message and photographs. David wrote:

‘I and my wife, Valerie, were in Hesedorf between about 1949 and 1951. I have attached a photo of the children and teacher from when we were at Stade School [below]. Valerie has her arms around the teacher, and I am second from the right, at the front. We have a memory that the teacher’s name was Mrs McGregor, but can’t be 100% sure.

I have attached another picture of the school’s Nativity play [below]. Unfortunately neither of the photographs have names or dates on them; they were taken by my mother, Lilian, who is no longer with us.

We went to school in a service vehicle, with an armed guard at the front and one in the back with us. In the winter, we had hot-water bottles, which were filled at home to go to school with, then filled at school to come home with – yes, we were very tough. All the desks were in a big circle in the room, not in rows, as is usual. At times, we walked in the woods singing a cuckoo song in German. Mrs McGregor had a Scottie dog that got run over in front of the school, which brought most of the school to tears.

We hope that Elaine can see herself in the photos. We would love to know if she can.’

Many thanks to David and Valerie for having shared their childhood photographs and memories of the school at Stade with us.

PRINCE RUPERT SCHOOL (PRS), WILHELMSHAVEN, GERMANY: THEN AND NOW

Prince Rupert School (PRS) Wilhelmshaven, which was situated in north-western Germany, educated the children of British military and civilian personnel stationed in West Germany between 1947 and 1972. A number of video clips taken from a three-hour-long DVD about PRS Wilhelmshaven, scripted by Barbara Steels and produced by John Leggett for The Willhelmshaven Association (TWA, see http://www.prs-wilhelmshaven. co.uk), can now be viewed on YouTube. Click on these links:

- to learn more about the background and opening of PRS Wilhelmshaven (http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=3GNejo6aKdc);

- to watch a family's home movie featuring Wilhelmshaven's Sportsplatz, aquarium and quayside, as well as a school sports day (http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=3p94KKRp38A);

- to see archive images of Collingwood House (http://uk. youtube.com/watch?v=XdrlVt-KXHI), Drake House (http://uk. youtube.com/watch?v=JGgRiU8DJlE), Rodney House (http://uk. youtube.com/watch?v=jVekYsLHwO8) and Howe House (http://uk. youtube.com/watch?v=r2x1tFlLC8);

- to watch footage filmed on the last day, in June 1972, of PRS at Wilhelmshaven (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mVYr03SGhCE);

- and to view recently filmed footage showing what the school's site and buildings look like today (http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=aX06P_ugYNs and http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=JPqwiukDPLg).

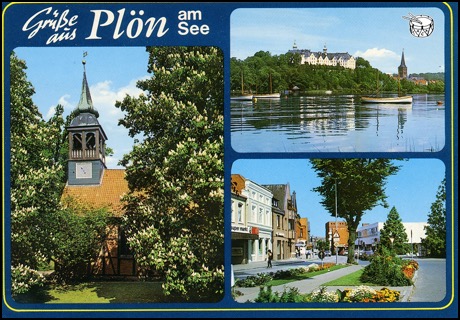

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: PLÖN AM SEE, GERMANY

The postcard below, which is captioned in German Das 700-jährige Plön a. See ('The 700-year-old Plön am See'), presents a view of Plön (or Ploen), a city on the northern shores of the Großer Plöner See (the larger of two lakes named for Plön), in the northern German Land of Schleswig-Holstein; click on this link to see a map of its location: http://ploen.alpha-kart.com/.

Plön was the home of the BFES' King Alfred School (KAS) between 1948 and 1959, and in the 'Links' section below, you’ll find further basic information on the school and a link to the associated Wyvern Club website. On this website, an interesting article, entitled 'Swords into Ploughshares' (http://www.kas-ploen.org.uk/HardStuff.htm), gives a potted history of the school's origins in Plön. In addition, the following link will take you to the city of Plön's official tourist-information website, which offers German-, English- and Danish-language options: http://www.touristinfo-ploen.de/tiploen/en/home/en_home_main.php; this website also provides more details of the city's history (see: http://www.touristinfo-ploen.de/tiploen/en/die_stadt_ploen/en_die_stadt_ploen_geschichte.php).

As is clearly stated, the colour postcard below combines greetings with various views of Plön am See. Although this postcard postdates the school, having been mailed during the late 1980s, the views that it presents would hardly have changed. It shows, moving clockwise from top right, the Schloß, or castle; a shopping street; and the Johanniskirche, or Johannis Church.

See also ‘KING ALFRED SCHOOL – THE STORY’, below, for details of Peter Dent’s film history of the school, which can be viewed on YouTube: https://youtu.be/OsmFbM9DA3M.

‘KING ALFRED SCHOOL – THE STORY’

Peter Dent, who was a pupil at King Alfred School (KAS) in Plön, (west) Germany, between 1952 and 1957, has produced a three-part film history of the school. As well as sending copies of it on DVD to former pupils around the world, he has made it available for all to watch on YouTube: https://youtu.be/OsmFbM9DA3M. Peter describes it as ‘a time capsule from the 1950s’, including as it does ‘a host of photographs and cine film showing the full range of activities at the school’. The film lasts for one hour and thirty minutes, and includes footage of Wyvern Club members (former KAS pupils) returning to the school – which is now the German navy’s Marineunteroffizierschule (MUS), or school for non-commissioned officers – on various anniversaries of its founding. For more on KAS, see 'BACKGROUND INFORMATION: PLÖN AM SEE, GERMANY', above.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: WIKIPEDIA ENTRY FOR KING ALFRED SCHOOL (KAS), PLÖN, (WEST) GERMANY

BOOK: CONCORDIA: THE WINDSOR SCHOOLS, HAMM, 1953–1983

In the introduction to his recently published e-book Concordia, Stephen Green writes, ‘This is a history of the Windsor Schools in Hamm, West Germany, run by the British Families Education Service. The school started in 1953 as a mixed secondary boarding school; in 1959 the school divided into boys’ and girls’ schools. In 1981 they remerged and closed in 1983. They were schools of the Cold War.’. The first part of the book, he explains, is a ‘narrative history of the schools’, while the second comprises a ‘series of self-contained thematic chapters’ and ‘the final chapter offers some reflections’. Concordia: The Windsor Schools, Hamm, 1953–1983 will not only be of interest to those who attended the schools, but also to those who are curious about the education of service children in Germany during the Cold War period. The e-book is available free of charge, and can be requested via https://prasino.eu/concordia-the-book/; by visiting the virtual Windsor School website: https://www.cicadastudio.com/wbshamm; and via the BFES/SCEA website: https://www.bfposchools.co.uk/archivepart3.

PERSONAL STORY: MY EDUCATION AS A MARRIED-QUARTERS' CHILD

Unless they are sent to a boarding school, most army children change schools as often as their parents are posted, which can be very often indeed. Chris Fussell has already contributed many illuminating memories of his childhood to TACA (see 'PERSONAL STORY: 'EVER HEARD A SHOT FIRED IN ANGER?'', 'PERSONAL STORY: BULLFROGS, CICADAS AND MACHINE-GUN FIRE IN EGYPT, 1951', 'PERSONAL STORY: WARTIME IN THE UK; PEACETIME IN MALTA, EGYPT AND OXFORDSHIRE', 'PERSONAL STORY: EXPERT FIRST AID IN MALTA', 'PERSONAL STORY: MAYHEM IN A MALTESE MARRIED QUARTER' and 'PERSONAL STORY: A MARRIED-QUARTER CRISIS IN EGYPT'). Here, he sums up his schooling.

'AGED THREE (1942, CARRICKFERGUS, NORTHERN IRELAND): in Northern Ireland in those days, school (Presbyterian) started earlier in Ulster than in England. (By then, Dad had been medically downgraded due to a head injury and had been seconded from the Royal Warwicks [the Royal Warwickshire Regiment] to the MPSC [Military Provost Staff Corps] in NI [Northern Ireland] Command.) I learned to read and write here, with a slate and pencil! I threw stones at kids from the neighbouring RC [Roman Catholic] school – it was just what us "Prod" [Protestant] kids did – we never really knew why.

AGED FOUR TO SEVEN (1944 TO 1946, ALDERSHOT, HAMPSHIRE, ENGLAND): following a move back "home" – a posting to Aldershot – there was no school for me as I was too young in England! My eight-year-old sister helped me to keep up with my reading. I started at school again at the age of five, and was ahead of my class due to that year in the Ulster school. I got into fights with other kids because of it! One fight resulted in a nose/sinus injury. The MO [medical officer] got Dad a posting to Malta in 1947 so that I could recover in a "nicer" climate!

AGED EIGHT TO TEN (1947 TO 1949, MALTA): in Malta, I went to an army children's school (but my big sister went to the joint-service, grammar-school-standard Royal Navy Dockyard school). School was from 0900–1300, six days a week, after which it was down to the beach in the summer. This gave me a great head start as a swimmer.

AGED TEN TO TWELVE (1949 TO 1951, HULL, YORKSHIRE, ENGLAND): having returned to England, Dad left the army in Hull. I went to a normal primary school and played left half at football.

AGED TWELVE TO FIFTEEN (1951 TO 1954, EGYPT): Dad having re-enlisted, we joined him in the Egyptian Canal Zone for four years, just after I had passed (in England) my Eleven Plus exam. I went to a really excellent, small (there were 200 pupils) secondary school in Moascar Garrison. I did well here, especially in English, and had three GCE [General Certificate of Education] London University external O' levels (including one in English literature) at the age of thirteen and a half! I went to the beach every afternoon, swam competitively and did RLSS [Royal Life Saving Society] Bronze Medallion lifesaving during school PE [physical education] time.

AGED FIFTEEN (1954, BICESTER, OXFORDSHIRE, ENGLAND): I went to Bicester County Grammar School for one year. They did not like my "unbalanced" O' levels much, but I topped them up with maths, physics and others that summer. I worked part-time for a market-square butcher's shop because I could not get a paper round to do.

AGED FIFTEEN TO SIXTEEN (1954 TO 1955, ARBORFIELD, BERKSHIRE, ENGLAND): having left school at just fifteen with six or seven O' levels, I went to the Army Apprentices School, Arborfield, to be a REME [Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers] apprentice telecommunications mechanic. Here, I started on my City & Guilds exams. I had to do Army Certificate of Education, first class, map-reading to complete my exemption from other ranks' education exams.

AGED SEVENTEEN ONWARDS (FROM 1956, WELBECK ABBEY, NOTTINGHAMSHIRE; SANDHURST, BERKSHIRE; AND SHRIVENHAM, WILTSHIRE, ENGLAND): I was now "kicked upstairs": firstly, to Welbeck College (where I gained A' levels in maths, physics and history); secondly, to RMA [the Royal Military Academy] Sandhurst (where I was runner-up for the military-history prize); and then to RMCS [Royal Military College of Science] Shrivenham (where I was awarded a BSc [Bachelor of Science] general degree in maths, physics and chemistry). But educationally, I was running out of steam (and interest in classroom life) by then and wanted to get on with being a soldier! So I joined the RAOC [Royal Army Ordnance Corps] because other Old Welbexians in the Royal Signals, Royal Engineers and REME seemed to spend all their time as young officers on courses, courses – and had a great time.

LOOKING BACK . . .

Hand on heart, none of us three Fussell kids who were dragged around from Blandford to Carrickfergus, to North Camp, Aldershot, to Malta, to Hull, to Ismailia, and then to Bicester, and so on, could claim that the army let us down. And what school kid would not envy the six-days-a-week, 9–1-pm-schoolday+down-to-the-beach routine? (Many years later, I recreated this lifestyle, in part, as a middle-aged management trainee for some logistics consultants in southern California.)

Oh, and did I mention that the selection of schoolteachers who elected to serve abroad in army children's schools were a really great and caring lot of people? I owed them a lot more than just my GCE O' levels. They were often supplemented by a number of Royal Army Education Corps officers and NCOs [non-commissioned officers] (regulars and national servicemen), especially for maths, map-reading, craft subjects and similar – they were a nice lot, too.’

Chris Fussell (b.1939).

PERSONAL STORY: EXPERIENCING LIFE IN TURKEY, ENGLAND, GERMANY AND LIBYA BETWEEN 1948 AND 1957

Janine Shirley has sent TACA a delightful photograph [below], of her class at Ratingen School, (West) Germany, in 1952. She writes:

‘My name was then Janine McQuillan, and my earliest travel memories are between 1948 and 1950, when my parents and I lived near Istanbul, Turkey. My father was a captain in the Royal Engineers, instructing the Turkish Army. We lived in a small village on the side of the Bosphorus called Kandilly. We were the only English family in the village, and l attended the local school as Istanbul was too far a ferry ride for a five-year-old.

From Istanbul, my father was transferred to Germany, and my mother and I were sent to the transit camp at the Grand Shaft Barracks in Dover [Kent]. I attended the local school, but spent much time on the beach. This meant many trips walking up and down the 190 historic steps of the shaft between the barracks and the town.

In 1950, we were reunited with my father in Germany. By this time, he had purchased and exported a white Austin A90 convertible sports car. He collected us in this car from the port at the Hook of Holland; we were destined for Brunswick [Braunschweig], and later Düsseldorf. I attended several army schools in Germany, but the one I remember most was in Ratingen [near Düsseldorf, in North Rhine-Westphalia]. The attached photo, taken in 1952, shows me in the front row, third from the right; next to me is my best friend, Gwen Major. The highlight of this period for me was the coronation celebration held at the Rhine Centre.

In 1954, we left Germany and went to Tripoli, Libya. I attended the army school at Azizia Barracks. In 1956, due to the Suez Crisis, all army wives and children were flown back to England. On 5 November, our flight crashed whilst landing at Blackbushe Airport, overshooting the runway and hitting trees. Several people died in the crash, including the aircrew. We later returned to Tripoli on a small merchant-navy cargo ship called the Syrian Prince. The ship, which left from the Manchester Ship Canal, had about twelve passengers, and we ate with the captain and crew.

We left Tripoli in 1957, travelling from Tripoli to Naples, in Italy, by boat; from Naples to Dieppe, in France, by train; and then taking the cross-Channel ferry to Newhaven [East Sussex]. I was thirteen by then.’

Janine would love to hear from anyone who remembers her from Ratingen School, Germany, or Azizia, Libya, or who had similar experiences within the time frames that she’s outlined. She can be contacted at janinemcq16@gmail.com. And we thank her for telling us about her eventful early years as an army child.

PICTURE: BFES PRIMARY BOARDING SCHOOL BRUNSWICK, (WEST) GERMANY, C.1950

We are indebted to Sheila Walker (née Bowen), whose father served in the 1st Royal Dragoons, for contributing the photograph below to TACA. Sheila writes:

‘The photo was taken in about 1950, when I was around ten. It shows staff and pupils at BFES Primary Boarding School Brunswick [Braunschweig], in [West] Germany, which was for army children. At the time, my father, Sergeant F V Bowen, was stationed at Northampton Barracks in Wolfenbüttel. All the children I travelled with from Northampton Barracks were day pupils. We were taken to school each day by an army 3-ton truck. This was something we took in our stride. I have a report signed by my class teacher, M Marshall, and my headmaster, J A Cook.’

If you attended this school, we would love to hear more about it.

PERSONAL STORY: SCHOOLDAYS IN BENGHAZI, LIBYA

Mick Kiernan lived in Benghazi, Libya, from 1951 to 1955 when his father, a clerk of works, was posted there. During this period, Mick was to all intents and purposes an army child, and attended Queen Elizabeth II Coronation School, a school for forces' children, from the ages of twelve to fifteen. In the extract from his memoirs that follows, he describes that school, as well as a memorable school camping trip to Ras el Hilal. (To read about the Kiernan family's stopover in Malta in 1951, click here; and for more on how Mick spent his leisure time in Libya, click here.)