Today, army children are generally either driven, transported by hovercraft, catamaran or ferry or flown to their new or current home (and most regard 'home' as being wherever it is that their parents are living rather than a specific house, village, town or even country), yet it was very different centuries ago. When on land, families once limped behind their soldier fathers on foot, be it straggling at the end of a column of military men on the campaign trail or as part of the baggage train. But if exposure to the elements, hunger and the myriad dangers of life on the road, and sometimes in hostile territory, was testimony to the tough life of many an army child during the early nineteenth century, worse fates frequently awaited them aboard troopships bearing them to such far-flung destinations as India. Indeed, if they weren't shipwrecked or killed by an infectious disease spread by the cramped, unsanitary conditions below deck, scurvy and other conditions caused by malnutrition or poor hygiene would put their health in great jeopardy. In short, if sea sickness was all that they suffered during the months that they spent onboard, then they were lucky.

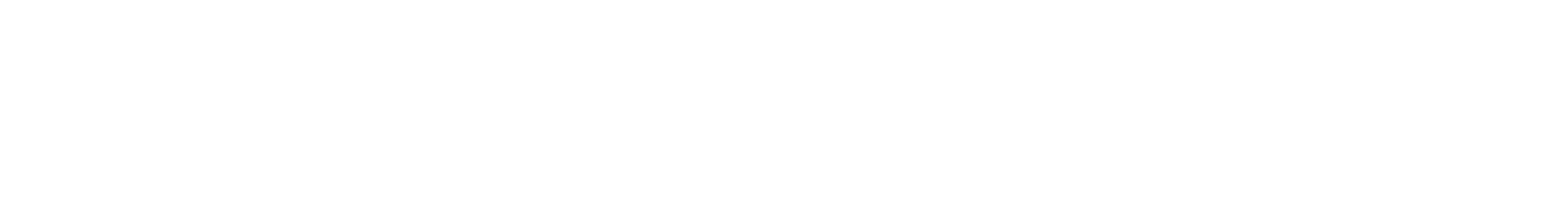

Women and children being given free warm clothing aboard a troopship (an illustration published in The Graphic of 3 August 1889).

Women and children being given free warm clothing aboard a troopship (an illustration published in The Graphic of 3 August 1889). And these were the fortunate ones, the ones who were privileged to be 'children of the regiment' rather than those 'off the strength', whose abandoned mothers literally had to fend for themselves and their brood when their husbands and fathers were redeployed.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the introduction of railways began to make being on the move safer and considerably more comfortable. And by the 1970s, the British Army was even chartering aeroplanes, so-called 'lollipop specials', to fly boarding-school-based army children from Britain 'home', to their families' married quarters in Germany, for the holidays.

PICTURE: ‘THE DEPARTURE FROM BRIGHTON’, 1796

The print reproduced below was engraved by John Murphy, after Francis Wheatley, and is one of a pair, the other being ‘The Encampment at Brighton’; these were published on 1 May 1796, with the original paintings dating from 1788. This print, ‘The Departure from Brighton’, depicts a baggage cart being prepared for a journey, with the tents that make up the soon-to-be-dismantled military camp in the background. In the foreground is a soldier of the light dragoons with his womenfolk and a baby – maybe the little group includes his wife and child, and perhaps they are camp followers, also readying themselves for the unit’s departure. Some camp followers of this period were lucky enough to be able to hitch a lift on a vehicle in the baggage train; most, however, had to follow behind on foot.

PICTURES: SOLDIERS ON A MARCH, 1805 AND 1811, BY THOMAS ROWLANDSON

The watercolour-and-graphite drawing below is by Thomas Rowlandson, and dates from 1805. Entitled Soldiers on a March, he added an explanation: ‘Soldiers and their baggage finding a river then they pack up their tatters and follow the drum’. Notable among the soldiers’ ‘baggage’ are women – army wives and other camp-followers – carrying their children (and, on the right, even a soldier).

The drawing belongs to the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, as does the later hand-coloured etching below, which was designed and published by Rowlandson in 1811 with the title Soldiers on a March: "To pack up her tatters and follow the Drum". Both illustrate how tough living and travelling conditions were for those early nineteenth-century army children who grew up ‘following the drum’ with their parents.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: THE ARMY WIVES AND CHILDREN OF HMS BIRKENHEAD, 1852

Peter Smith has contacted TACA with the following request for information.

‘The most famous troopship disaster of the Victorian era was the loss of the Birkenhead off the Eastern Cape in January 1852. It led to the world-famous phrase, "women and children first”. I am researching a book on this subject, yet nowhere so far have I been able to obtain a full and detailed list of the names of the women and children passengers – army wives and children. I have the surnames of the women, and of some of the children, but, considering the incident’s worldwide fame, I find it incredible that no such list appears to have been kept. Could anyone help? There is nothing at the National Archives in Kew, or the National Army Museum in Chelsea, or in the various regimental museums. I’ve read ALL the printed books dating back to 1852, and have contacted all likely museums, here and in South Africa – nothing.’

If you think that you can help Peter, please e-mail him at petercsmith@supanet.com.

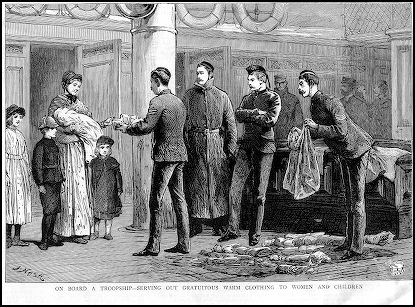

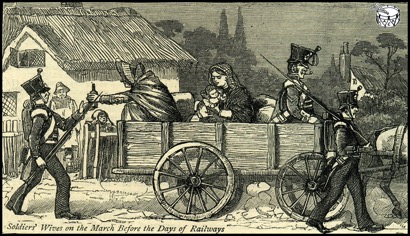

PICTURES: ARMY WIVES AND CHILDREN ON THE MARCH ("TOMMY ATKINS" MARRIED – PAST AND PRESENT, 1884)

The images reproduced below are details taken from "Tommy Atkins" Married – Past and Present, a print that was published in The Graphic on 12 January 1884 (click here to see it). Entitled 'Soldiers' Wives on the March Before the Days of Railways' (above) and 'A Married Soldier on the March in India' (below), both illustrate the basic ways in which soldiers' wives and children were once transported when allowed to accompany their husbands and fathers from posting to posting during the nineteenth century (and earlier).

Above: 'Soldiers' Wives on the March Before the Days of Railways'.

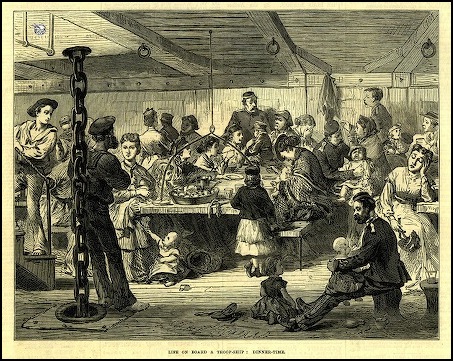

PICTURE: 'LIFE ON BOARD A TROOP-SHIP: DINNER-TIME'

The illustration below, specified as being from a sketch made on board the troopship the HMS Himalaya by Major W O Carlile, of the Royal Artillery, appeared in the 6 December 1873 issue of The Illustrated London News. The text that accompanied it described how fifteen to twenty men would sit down at each mess-table to eat at noon every day, when 'the soldiers behave with their usual gallantry and courage, let the weather be smooth or rough'. 'Where the wives and children of soldiers are on board, the scene at their dinner-time is much less agreeable', the piece continued disapprovingly. 'They are too commonly huddled together in a close atmosphere below, rendered more unpleasant and unwholesome by the want of convenience for washing. While many are sick, others are crying or squabbling, and the voyage is a severe trial to them. A few kind husbands will come down to look after the comforts of their wives and babes. Such men, it is said, are invariably found the bravest soldiers in the field of battle, the most patient and constant in a fatiguing march.'

For another illustration from the same issue of The Illustrated London News, see below: 'PICTURE: 'LIFE ON BOARD A TROOP-SHIP: "COMMENCE FIRING"''.

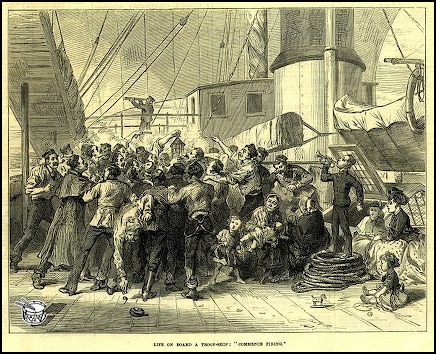

PICTURE: 'LIFE ON BOARD A TROOP-SHIP: "COMMENCE FIRING"'

One of the illustrations based on sketches by Major W O Carlile, of the Royal Artillery, that were published in the 6 December 1873 issue of The Illustrated London News (for another, see 'PICTURE: 'LIFE ON BOARD A TROOP-SHIP: DINNER-TIME'' above) depicts a riotous scene witnessed by a few startled-looking army children.

The caption explains the illustration's title: 'Smoking tobacco is allowed at meal-hours – breakfast, dinner, and supper – and after the evening inspection, till a quarter to eight o'clock, when all pipes must be extinguished. The only lawful place for the men smoking is on the upper deck before the mainmast; officers smoke near the mizenmast. The signal for lighting pipes is facetiously called "Commence firing!" and it is given by a blast of the bugle, after the evening inspection'. The troopship depicted is the HMS Himalaya, an iron screw steamer that was launched in 1853 and that served as troopship until 1895, when she was converted to a coaling hulk. She was sunk in 1940 in Portland harbour, Dorset, during a German bombing raid.

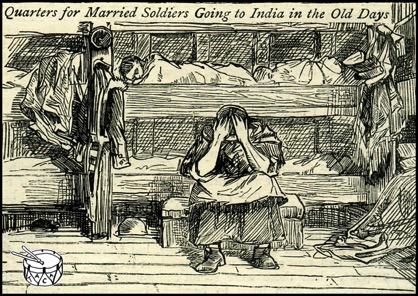

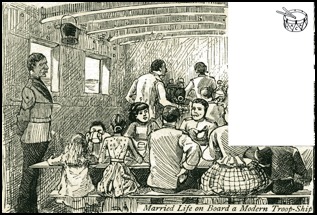

PICTURES: CONDITIONS FOR NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY FAMILIES ABOARD TROOPSHIPS ("TOMMY ATKINS" MARRIED – PAST AND PRESENT, 1884)

Shown below are three details from a composite print entitled "Tommy Atkins" Married – Past and Present, which was first published in The Graphic on 12 January 1884 (to see it, click here). Intended to contrast conditions aboard troopships for those army wives and children who were permitted to accompany their soldier menfolk on overseas postings (to India, for example) before and after improvements had been made during the second half of the nineteenth century, the first, 'before' image presents a cramped and desperate picture. Although the second and third, 'after' images give the impression of the women and children enjoying spacious and orderly living and eating quarters, the reality would no doubt still have been crowded and uncomfortable.

Above: 'Quarters for Married Soldiers Going to India in the Old Days'.

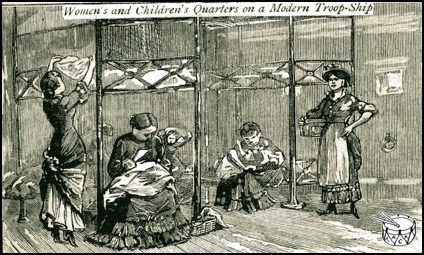

Below: 'Women’s and Children's Quarters on a Modern Troop-Ship'.

PICTURE: 'PERFECT LITTLE DEVILS'

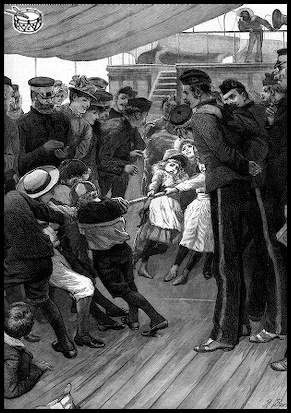

This illustration appeared in The Graphic newspaper on 29 October 1887. It is captioned 'Children's tug of war on a homeward-bound troopship, boys versus girls'.

Commenting on the behaviour of army children travelling aboard the steamer Ottawa from Bombay (now Mumbai), India, to England in 1858, a certain Major Bayley observed: '. . . heaven forbid that I should ever again find myself on board ship in company with children brought up in India. They were perfect little devils; and for the first day or two we had a fine time of it, as many of the passengers were cripples and unable to move after them . . .' (Bt-Maj J A Bayley, Reminiscences of School and Army Life, 1839-1859, London, 1875, quoted in Richard Holmes, Sahib: The British Soldier in India, 1750-1914, HarperCollins Publishers, London, 2005, p.98).

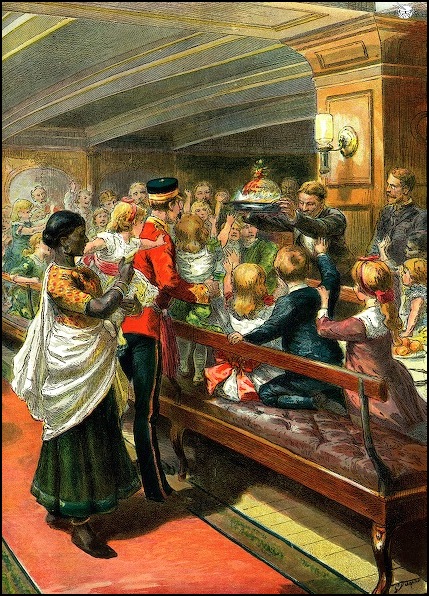

PICTURE: CHRISTMAS DINNER ON A TROOPSHIP, 1889

This sketch of some excited army children being served Christmas dinner at sea was made from a drawing by G Durand depicting a scene observed on a homeward-bound troopship (which had presumably set sail from India, given the presence of the ayah in the foreground). It was first published in the Christmas edition of The Graphic in 1889.

PICTURE: MILITARY FAMILIES ARRIVING IN RIEHL, GERMANY, 1922

The caption printed on the black-and-white postcard below states that the scene pictured shows ‘military families arriving Rhiel, 26.3.22’, in Germany. ‘Rhiel’ should, in fact, read ‘Riehl’, this being a suburb of the Rhineland town of Köln/Cologne that was occupied by the British Army following World War I until around 1926.

PERSONAL STORY: CROSSING THE PACIFIC, 1930

Mairi Paterson and her mother and brother had sailed in May 1928 from Liverpool to Jamaica to join her father, who was serving with the 2nd Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. (To read Mairi's description of the two years that she spent in Jamaica, click here: 'PERSONAL STORY: 'IT WAS A MAGICAL PLACE, WITH PALM TREES AND COFFEE PLANTATIONS', JAMAICA, 1928–30'.) In the following instalment of her account of growing up as an army child between 1921 and 1938, Mairi recalls crossing the Pacific aboard a troopship in 1930, on the journey from Jamaica to her father's next posting in Wei-Hai-Wei (or Weihai), north-eastern China. As Mairi notes, the ship's passengers were the first British troops ever to pass through the Panama Canal, and to dock in Honolulu. (Click here to read the next part of Mairi's story, telling of her two years in Wei-Hai-Wei: 'PERSONAL STORY: 'I AM GLAD THAT I CAN REMEMBER WEIHAI AS IT WAS EIGHTY YEARS AGO’’; here to read of her subsequent two years in Hong Kong: 'PERSONAL STORY: GOING TO SCHOOL BY RICKSHAW AND KEEPING A LOW PROFILE IN HONG KONG, 1932–34’; see below to read of her journey back to Scotland: ‘PERSONAL STORY: SAILING FROM HONG KONG HOME TO SCOTLAND, 1934’; and click here to read of her time living at Stirling Castle: ‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘NOW I WAS LIVING IN A CASTLE: STIRLING CASTLE’, 1934’.)

'The next stage of the battalion's "tour of overseas duty" took us a very long way. We were now posted to northern China. After a hectic period of packing and saying goodbye to the friends we had made (a constant of being an army brat), we boarded a rather elderly troopship, the City of Marseilles, of the Ellerman City Line. It was very overcrowded, with a whole battalion, plus wives and children, on board, and we children became very adept at utilising any space we could find for games.

Going through the Panama Canal was one of the most memorable events. I can still remember standing on the deck and looking down at the people on the docks. We were so close that we could see their expressions and return their waves. We were the first British troops to pass through the canal, and this generated a lot of interest.

At last we saw the Pacific stretching ahead of us and started on the long voyage. It lasted more than five weeks, and gave me an abiding love of being on board a ship. Two incidents broke the routine of shipboard life. The first was reaching Hawaii and docking in Honolulu for three days. Again, we were the first British troops to visit, and were given a civic welcome. The battalion, led by the pipe band, marched through the streets to cheering crowds; local residents, particularly expatriates, entertained us every day. I remember visiting a pineapple farm and watching hula dancers on Waikiki Beach. The second incident occurred when we crossed the Date Line: Neptune, complete with wild white hair, a long white beard and a trident, came on board and, after a great deal of horseplay, gave us permission to proceed.

Eventually, we arrived in Shanghai, and were told that C Company, our company, was to be put ashore at Wei-Hai-Wei, on the tip of the Shantung [or Shandong] Peninsula, while the rest of the battalion went further north, to Tientsin [or Tianjin]. Britain had leased a strip of land, 3 miles deep and 10 miles long, on which were stored tanks of water and fuel and godowns [warehouses] holding stores of food, medical supplies, etc. Every summer, the rather grandly titled British Fleet in China Waters came north for manoeuvres, mainly off the coast of Korea, then part of communist Russia. C Company's job was to look after these supplies.

The little village of Wei-Hai-Wei, with only four shops, followed the crescent shape of the harbour, looking across at the island that made it so sheltered. The ground rose at each end, and there was a larger building on each point. One looked very closed, with shutters over the windows, but the other, more Chinese in style, was occupied. Our camp was behind the village, and, further back, the hillside rose quite steeply to a gap between two large rocks, beyond which we were not allowed to go. At that time, the north had a communist government, with the capital in Peking [Beijing], while the south was ruled by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party, with Nanking [Nanjing] as the capital. In between were the notorious warlords.'

Mairi Paterson (née Campbell, b.1921).

PERSONAL STORY: SAILING FROM HONG KONG HOME TO SCOTLAND, 1934

Although she was only thirteen when she sailed from Hong Kong to Scotland in 1934, this was not the first long sea voyage that Mairi Campbell had undertaken: not only had she travelled from Liverpool to Jamaica in 1928 (see 'PERSONAL STORY: 'IT WAS A MAGICAL PLACE, WITH PALM TREES AND COFFEE PLANTATIONS', JAMAICA, 1928–30'), but two years later, she had sailed across the Pacific Ocean (‘PERSONAL STORY: CROSSING THE PACIFIC, 1930’, above) from Jamaica to Wei-Hai-Wei (Weihei), in north-eastern China, where she lived until 1932 (‘PERSONAL STORY: 'I AM GLAD THAT I CAN REMEMBER WEIHAI AS IT WAS EIGHTY YEARS AGO’’). Two years in Hong Kong followed ('PERSONAL STORY: GOING TO SCHOOL BY RICKSHAW AND KEEPING A LOW PROFILE IN HONG KONG, 1932–34'), and came to an end with the news of Mairi’s father’s next posting: to Stirling Castle, the regimental depot of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, in Scotland (and click here to read of her time living at Stirling Castle: ‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘NOW I WAS LIVING IN A CASTLE: STIRLING CASTLE’, 1934’). In the following instalment of her story, Mairi recalls the journey back to Scotland, where she had last lived in 1922.

‘This time, we were not on a troopship, although there were many army personnel and their families on board. There was a cheerful atmosphere and quite a lot of friendly amateur entertainment. We played housey-housey (bingo?), and there was a good library, which I enjoyed.

Our first stop was at Singapore, where we went ashore and saw all the local sights, including a fine temple outside which we had to leave our shoes. Then we were away again on a long haul across the Indian Ocean until we reached Colombo, in what was then Ceylon (and is now Sri Lanka). I thought that it was a beautiful town, not so busy and so frightening as Singapore. Then we sailed up the coast until we reached Bombay – now Mumbai – in India. I remember boats coming alongside laden with heaps of fruit and other goods. The prices were shouted up to us, money was lowered in a bag over the side, and then up came the fruit. We were ashore for only a short time, to my relief. It was incredibly noisy.

The next part of the voyage was very exciting. We were going through the Suez Canal. I had expected something like the Panama Canal, but it was very different: it was not so narrow, and the journey was a great deal more leisurely. We went ashore at Port Said, and as I had read a great deal about the pharaohs and the pyramids, I was very thrilled to be on Egyptian soil. However, there were no regal figures or grand tombs to be seen – only a great many persistent beggars!

The Mediterranean was a great change from the earlier part of the voyage. It was much cooler now than it had been, and hot drinks were offered to us mid-morning. We were twice ashore: in Malta and in Gibraltar. I loved Valletta, and was fascinated by a man driving a flock of goats along the street. From balconies above, cans were lowered on ropes. The goats were milked into them, and the cans were then carefully drawn up again. Gibraltar was strange – foreign, yet British. We climbed up to the top of the Rock, which gave us wonderful views of Africa, which appeared so close. My abiding memory is of having a banana snatched from my hand by one of the apes, who gobbled it up immediately.

We were now on the way home. The weather grew colder, and the Bay of Biscay was quite rough, but at last we went ashore at Southampton. On the train to London, I was surprised by how small the fields were. Next, it was the overnight train to Glasgow. I remember thinking that when I woke up, I would be in Scotland, surrounded by hills and heather – a very romantic view! I actually woke up on the outskirts of Glasgow. However, after we reached Arrochar, a car took us around the head of Loch Long and up the magnificent hill road, the Rest and be Thankful, to the little village of Lochgoilhead, where my grandfather welcomed us.’

Mairi Paterson (née Campbell, b.1921).

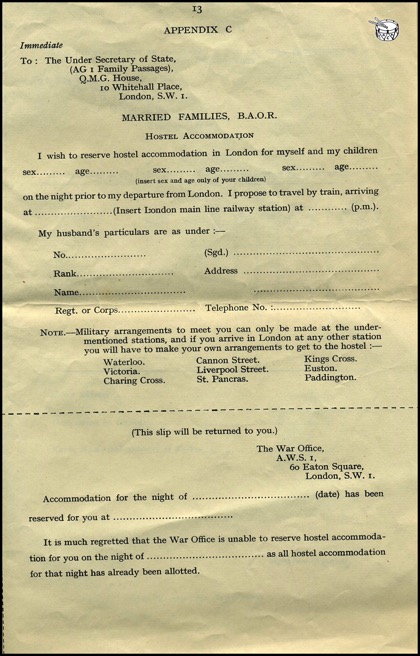

GUIDE TO FAMILIES PROCEEDING TO B.A.O.R., AUGUST 1946: TRAVEL

Guide to Families Proceeding to B.A.O.R., a booklet issued by the War Office in August 1946 to army families who were preparing to join soldier husbands and fathers who had been posted to the British Army on the Rhine, outlined various issues relating to their travel preparations. Reproduced below are selected extracts from the booklet concerning passports, visas and military permits; clothing coupons; baggage arrangements; money; domestic animals; and hostel accommodation in London and the wearing of BAOR badges. (And click here to read extracts regarding medical matters, and here for guidance concerning children’s education.)

‘Passports, Visas and Military Permits

5. In ordinary circumstances a passport is required by all persons leaving the United Kingdom and a visa is needed to enter or pass through countries possessing sovereign rights. A military permit is required to enter countries under military government.

Families proceeding to B.A.O.R., who are joining their husbands in Germany, will sail direct to Cuxhaven and will, therefore, not require visas. In order to avoid delay in the departure of families, it has also been agreed that families going to Germany may proceed without passports, provided they have a military permit to enter the British zone in Germany and make application for a passport before they leave the United Kingdom. You should, however, appreciate clearly that you will NOT normally be able to leave Germany without a passport.

Families joining their husbands in countries other than Germany must obtain passports and visas before they leave Britain.

Similarly persons born or resident in EIRE must obtain EIRE passports before they leave that country, whatever their destination may be.

6. Passports.

The following points affecting the validity of passports should be noted:

Children … Particulars of children under the age of 16 who are accompanying you must be entered on page 2 of your own passport. Children aged 16 or over must hold separate passports.

Supplementary Clothing Coupons

8. An issue of supplementary clothing coupons is made, on behalf of the Board of Trade, to the families of military personnel proceeding overseas, to enable them to buy any additional clothing necessary for the journey, and to provide for one year in the country to which they are going. This issue is made subject to the condition that any supplementary coupons NOT used before the departure of the family, are returned to the War Office. If for any reason a family does not proceed overseas, all unused supplementary coupons must also be returned.

Children of 14 years of age and over are given the same number of coupons as adults; children under that age receive half the number.

Families should retain their Clothing Books whether all the coupons have been used or not.

Baggage Arrangements

9. The scale of total baggage allowed for families proceeding to B.A.O.R. is as follows:

Wives of Lt.-Cols. and above . . . 8 cwts.

Wives of Majors, Captains and Subalterns . . . 6 cwts.

Wives of Warrant Officers . . . 5 ½ cwts.

Wives of other ranks . . . 4 ½ cwts.

Each child . . . 1 ½ cwt. and pram.

Bicycles may be sent within the above entitlement.

10. Accompanied Baggage.

Of the total quantity allowed, families may actually take with them not more than 1 cwt. in respect of the wife and ½-cwt. plus a folding pram in respect of each child. Baggage required on the journey should be packed separately from that not required.

Money

16. You will be allowed to exchange £5 for yourself and £5 for each of your children into B.A.F.S.V.s (British Armed Forces Special Vouchers). This is the only type of currency which you will be able to spend in Germany and English money will be useless to you. Arrangements have been made for this exchange to be made before you embark.

Domestic Animals

17. Domestic animals, such as dogs and cats, cannot at present be taken in military transports and any application for permission for them to accompany you will be refused.

Your Journey––Hostel Accommodation in London

20. Full details and a warrant to the port of embarkation will be forwarded to you when your movement instructions are issued.

If however, you require help to reach the railway station nearest to your home you should ask your local Women’s Voluntary Service Centre for assistance. Representatives of the W.V.S. will also be available to help you, if necessary, at some of the principal main line railway centres on the way to London.

To help you with your luggage, etc., and to give any directions you may need, arrangements have also been made for assistance to be available at the following Stations in London:

Waterloo

Victoria

Charing Cross

Cannon Street

Liverpool Street

St. Pancras

King’s Cross

Euston

Paddington.

Should you require to stay over-night in London, limited government hostel accommodation is available and may be reserved through the War Office. The following points should, however, be noted:

(a) The accommodation is strictly limited and is only intended for families who cannot reach London by noon on the day of departure.

(b) Accommodation at government hostels can, therefore, only be booked for one night preceding the day of your departure.

(c) Only one class of accommodation is available but bed, bath and breakfast will be provided at reasonable rates.

The slip at the foot of the form [see below] will be returned to you to let you know either at which hotel accommodation has been reserved for you or that accommodation is not available.

A blue “B.A.O.R.” badge is forwarded with this Guide for each member of the family travelling. These badges should be worn tied to your lapel or to a button on arrival in London to enable the military personnel and the W.V.S. at the railway station to identify you and to know to whom assistance should be given. It is also suggested that you should print the names of your children on the back of their badges so that they may be identified easily if they should become separated from you.

Note.––Travel to Germany will normally be via Tilbury and to the Low Countries via Harwich and you will only be required to travel via London if it is necessary for you to do so to reach your port of embarkation.’

MAGAZINE ARTICLE: ‘SERJEANT NYLAND’S SONS SAIL TO A NEW HOME’, FEBRUARY 1948

We are indebted to Stewart May for contributing the article below to TACA. Published in Soldier magazine in February 1948, it describes how the army helped to reunite Serjeant [sic] Nyland’s sons with their father.

The text reads as follows:

‘AND HERE’S ANOTHER STORY WHICH SHOWS THE ARMY HAS A HEART . . .

SERJEANT NYLAND’S SONS SAIL TO A NEW HOME

For six years ex-Staff-Serjeant P. E. Nyland of the Royal Pioneer Corps had not seen his five sons.

Throughout his 13 years, the eldest of these sons, Jimmy, had not even seen his brothers. He was a cripple, in the care of the Shaftesbury Society’s home at Hurst Lea, Sevenoaks.

But on the last day of last year Jimmy met his brothers – at Southampton, where the five were brought together to embark on the Durban Castle for South Africa. By the time this article appears the five lads – Jimmy, Anthony, David, Terry and Keith – will have been reunited with their father in Durban.

The war brought domestic setbacks to Staff-Serjeant Nyland. When his service was over he chose to strike out in a new land and took his release in South Africa. As soon as he was set up in a good job he applied for his sons to be sent to join him.

Anthony, David, Terry and Keith had been looked after for four years by the Nottingham Education Committee. They were virtual orphans.

The Army took over the task of reuniting the sons with their father. It tackled all the paper work, it secured reservations, it bore the cost of the passages.

At the last minute there was a hitch. The shipping company could not accept the children without someone to take charge of them during the voyage. The Army is used to last-minute hitches. This one was overcome when two Roman Catholic priests, also travelling on the Durban Castle, undertook to look after the five boys.

What did the lads think of their adventure? Well, look at the photograph and their faces will give you a good idea.

Boarding the Durban Castle: Jimmy, Anthony, David, Terry and Keith Nyland with Fathers Ryan and Fitzgerald.’

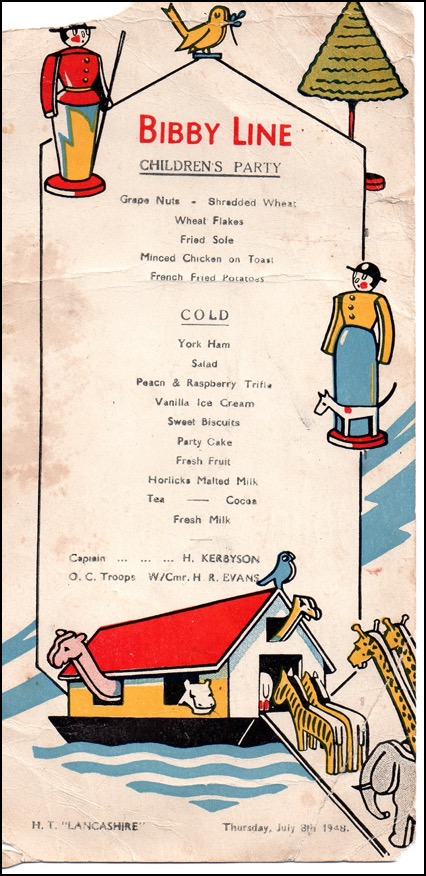

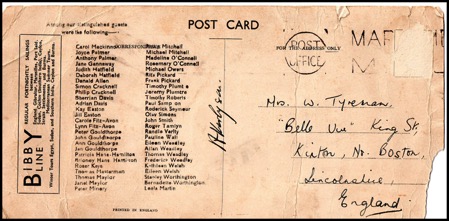

PICTURES: CHILDREN’S PARTY ABOARD THE HMT LANCASHIRE, 1948

On 8 July 1948, Tim Roberts (who was born in 1946) was one of the young guests at a children’s party held aboard HMT [hired military transport] Lancashire, as he explains:

‘In 1947, my father, then corporal, later WO II, Frank Roberts, of the RAPC [Royal Army Pay Corps], was posted from the War Office in London to the Far East. He made his way via short-term attachments in India and Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), to Hong Kong. It wasn’t until the summer of 1948 that my mother was able to secure an unaccompanied passage to join him in Hong Kong. She travelled with me, aged 19 months, on HMT Lancashire, and spent most of the voyage being seasick. I, apparently, rather enjoyed life aboard the ship, and the children’s party was a highlight. My father’s next posting was to the RPO [Regimental Pay Office] Nottingham, and we returned en famille, complete with my new brother Martin, on the Empire Orwell in July 1950.’

Tim has contributed the party menu (below) to TACA, on which it is recorded that the children were treated to grape nuts, shredded wheat, wheat flakes, fried sole, minced chicken on toast, French fried potatoes, York ham, salad, peach & raspberry trifle, vanilla ice cream, sweet biscuits, party cake, fresh fruit, Horlicks malted milk, tea, cocoa and fresh milk.

On the reverse of this memento (below) are listed the names of the ‘distinguished guests’, fifty-two in all:

‘Carol Mackinnon, Joyce Palmer, Anthony Palmer, Jane Gannaway, Judith Hatfield, Deborah Hatfield, Donald Allen, Simon Cracknell, Philip Cracknell, Sherrian Davis, Adrian Davis, Kay Easton, Jill Easton, Carole Fitz-Avon, Lynn Fitz-Avon, Peter Gouldthorpe, John Gouldthorpe, Ann Gouldthorpe, Jan Gouldthorpe, Patricia Hans-Hamilton, Briony Hans-Hamilton, Roser Keys, Thomas Masterman, Thomas Maylor, Janet Maylor, Peter Minery, [?] Mitchell, Michael Mitchell, Madeline O’Connell, Rosemary O’Connell, Michael Owers, Rita Pickard, Frank Pickard, Timothy Plumtre, Jeremy Plumtre, Timothy Roberts, Paul Samp[?]on, Roderick Seymour, Olav Simons, John Smith, Roger Tamlyn, Randle Verity, Pauline Wall, Eileen Weadley, Allan Weadley, Thomas Weadley, Frederick Weadley, Kathleen Welsh, Stanley Worthington, Bernadette Worthingon, Leela Martin’

Tim writes: ‘it would be fascinating if any of the other guests at the Lancashire party responded’. It certainly would, and if your name is on the guest list, we’d love to hear from you.

PERSONAL STORY: SWIMMING WITH DOLPHINS, A REMARKABLE INCIDENT WITNESSED EN ROUTE TO JAMAICA, 1951

June Sage (née White, b.1942) has been in touch to share her recollections of a memorable sea journey to Jamaica, ‘where my father, then a lieutenant-colonel, had just been appointed Commander Royal Engineers (CRE)’.

‘In 1951, I travelled on the SS Empire Test to Jamaica, We berthed at the Azores in order to take on coal and then crossed over to Bermuda.

On the way to Bermuda, I have a vivid recollection of the ship turning around, with all the passengers looking over the side – a mother had been watching some dolphins with her child in her arms. As she was watching, the child slipped and fell into the water. The ship took about twenty minutes to turn and return to the spot where the accident had happened. Unbelievably, there were dolphins circling, with the baby in their midst. When the sailors launched a lifeboat, they found the baby asleep and unharmed – the dolphins had been circling to keep it safe from harm. Does anyone else remember this remarkable incident? Did it ever reach the press?

When we arrived, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers were there with their commanding officer (CO), Colonel Jimmy Johnson. After they left, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI) came out. During our stay, the army was based at Up Park Camp in Kingston, and also in the hills at Newcastle – such a beautiful resort. We returned, by air, in 1953. I could write pages about my time in Jamaica – we had the Coronation parades and the Queen also visited while we were there. But I'm not sure if anyone would be interested, just lots of old memories!’

We are sure that plenty of people would be interested in learning more about June’s life as an army child. And if you think that you can throw further light on the extraordinary scene that she witnessed aboard the SS Empire Test, please either e-mail June (prunie@btinternet.com) or contact TACA.

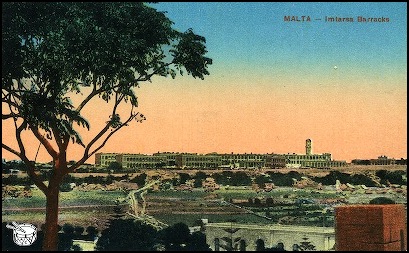

PERSONAL STORY: 'MALTA SEEMED VERY EXOTIC TO ME'

Mick Kiernan attended Queen Elizabeth II Coronation School, a school for forces' children, after his father, a clerk of works, was posted to Benghazi, in Libya, in 1951, when Mick was twelve. (To read more about Mick's schooldays in Benghazi, click here; and for how he spent his leisure time in Libya, click here.) The Kiernan family remained in Libya until 1955, and was so closely integrated into the British military community that Mick might as well have been an army child. Here, he describes stopping over in Malta in 1951, en route from his hometown of Colchester to his new home in Benghazi.

'From Nice, we completed the second leg of the journey to Luqa airport on the island of Malta GC. I remember the heat that hit us upon leaving the plane and the smell in the air as we walked down the steps to the runway. This was our introduction to the Middle East, and from here on almost everything would be very different to the way of life that we had been used to in England.

We were taken by bus to Imtarfa, which, at that time, was a transit camp for military and civilian personnel, and here we stayed for a week before the voyage to Tobruk in Libya. Imtarfa was sited on one of the highest points of Malta, and from here we could see the island laid out before us in all directions, showing its clusters of villages and towns, with their flat-roofed, sandstone buildings and tall, majestic churches. Beyond these built-up areas, the farmland had been built up into terraces to prevent the soil from being washed away down the hills when the rains came. It was all quite different to the England that I had been growing up in. Here, the people still used horse-drawn carriages, and some of the older women wore the traditional black hood and cape called a faldetta. Their language was unlike anything that I had heard before, and conversations were held in what to me sounded like loud and aggressive voices. I felt that at any moment a fight would begin.

Below: The barracks at Imtarfa.

Malta seemed very exotic to me. The England that we had left behind still had rationing for most things, but here on Malta, nothing was rationed. Shops were full of sweets and all kinds of goodies, including tinned peaches, which I had previously tasted only at Christmas. On a visit to Valletta, I bought a large tin of peaches, which I ate once back in our room in Imtarfa, and spent the night feeling quite sick. (It was worth it, though!) There was a clock tower in the camp, which rang the hours day and night, so nobody got a complete night's sleep.

Our days passed with journeys to Valletta on the brightly coloured Maltese buses, with their shrines to the Virgin Mary or Jesus located next to the driver. When getting on or off the bus, the Maltese would cross themselves to ensure a safe ride or thanks for a safe trip completed. During one of our shopping trips to Valletta, my mother bought me a straw hat to wear when we arrived in North Africa. I think that in her mind we were off to the Dark Continent, where I might get sunstroke if my head were exposed to the hot sun.

One day, we walked the 3 or 4 miles from Imtarfa to nearby Rabat, where we took a guided tour of the catacombs in which the early Christians were entombed. It was very creepy. Our guide was a cadaverous old man who smelled very strongly of garlic, which was impossible to avoid in the confined, underground spaces. He took delight in relating the story of a young girl who refused to submit to a Turk, who then had the girl's breasts cut off. There was a picture of the breasts on a tray, which both shocked and fascinated me. After this, we walked to the nearby gateway and entered the ancient, silent city of Mdina, where we explored the narrow streets and visited the cathedral. As a Catholic, I found the churches fascinating, and very impressive, with their ornate stonework and brightly decorated interiors – quite unlike the rather conservative churches in England.

At the end of our week's stay on Malta, we travelled across the island by army bus to the Grand Harbour, where we boarded a Royal Navy corvette for the voyage that would take us some 300 miles to the port of Tobruk. My only recollections of this trip are of being on deck in the hot sun looking out for dolphins and flying fish, and then, at night, of bedding down in a very hot, tiny cabin. When we arrived in Tobruk, the town still showed signs of the siege during World War II, when Allied forces were holding off Rommel's Afrikakorps. There were many wrecked ships in the harbour, and few buildings left standing in the town. Here, we met up with my father, who had travelled the 300 or so miles from Benghazi to meet us. To my relief, he quickly discarded my straw hat before we got on to the bus for the journey to our new home.'

Mick Kiernan (b.1939).

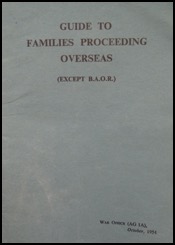

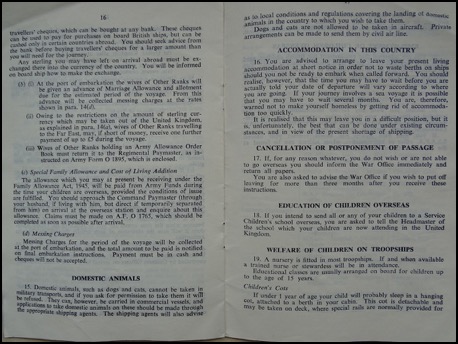

PICTURES: TROOPSHIP TIPS, BOAC TICKETS AND TRAVELLING TO AND FROM TRIPOLI, LIBYA, 1950S

Below: Pages from Barbara’s ‘Guide to Families Proceeding Overseas (Except B.A.O.R.)’, dated October 1954.

One of the sections in the guide is headed ‘Welfare of Children on Troopships’, and reads as follows:

’19. A nursery is fitted in most troopships. If and when available a trained nurse or stewardess will be in attendance.

Educational classes are usually arranged on board for children up to the age of 15 years.

Children’s Cots

If under 1 year of age your child will probably sleep in a hanging cot, attached to a berth in your cabin. This cot is detachable and may be taken on deck, where special rails are normally provided for suspension of cots during daytime. If, however, you possess a Karricot, or similar article, you are advised to take this with you for use during the day as you will probably find it more convenient.’

Another section, headed ‘Baby Foods on board Ship and Aircraft’ reads:

‘Troop Transports carry a stock of the following baby milk foods, which are issued free when required to mothers with young children. (Full Cream and Half Cream varieties of each).

National dried Milk

Cow & Gate

Ostermilk

Trufood

If you require any other brand of baby food you should arrange to take a sufficient supply with you, as the above are the only brands available in the ships. On Air Trooping Services baby foods required should be taken with you.’

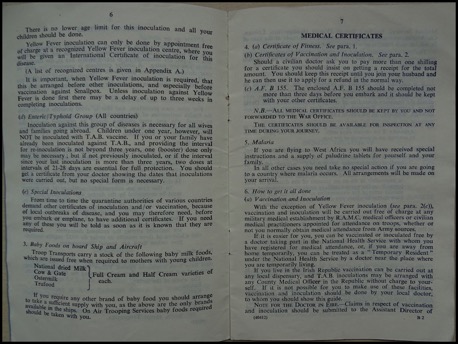

Of Tripoli, Barbara recalls that ‘We flew out there in ’54, although I was too young to remember it. But I do remember being evacuated in ’56 for the Suez Crisis. We flew out in an old Dakota, and my mum always said that that was its last flight! We landed in Malta and then continued back to England. When it was all over, we flew back to Tripoli in December ’56 with BOAC [British Overseas Airways Corporation] and I’ve still got the ticket (below). At the end of our posting, my dad decided to drive home, and so we had a great adventure driving from Tripoli via Algeria and France back to England in a lovely old American Chevvy [Chevrolet]!’

Below: The BOAC ticket that enabled the Messenger family to fly from London to Tripoli’s Idris Airport on 14 December 1956.

Below: A photograph of the Messengers’ Chevvy being lifted on to the ferry in Algiers, for the crossing to France.

Our thanks go to Barbara for her latest contributions to TACA.

TACA CORRESPONDENCE: LOOKING FOR A SINGAPORE-TO-ENGLAND FLIGHT ROUTE, 1957

Brian Child, whose father served in the Royal Signals, has contacted TACA with a request for help.

‘I was born in 1947, in Stoke Newington, later moving to Aines Lines, Catterick Camp, Yorkshire. I lived in Serrangoon Garden Estate, Singapore, from 1953 to 1957, and attended Alexandra Primary School. I later lived in Germany, on Königsberger Straße, Bad Salzuflen, near Herford, in North Rhine-Westphalia, and was schooled at Prince Rupert School (PRS) Wilhelmshaven, and Kings School, Gütesloh.

I am writing a short memoir for my grandchildren, and I cannot recall the route we took in 1957 when flying back to England from Singapore. I was hoping someone could jog my memory. The only airport I can remember, other than Changi, is Istanbul. We flew in a Bristol Britavia aircraft. The flight we were on had to reroute from a London airport due to bad fog, and we landed at Prestwick, I believe. Is there any way that I can obtain this information?’

If you think that you can help Brian, please e-mail him at brian.l.child@btinternet.com.

PERSONAL STORY: SCHOOL TRANSPORT IN NAIROBI, KENYA, C.1960

Robert Taylor, whose father served in the King’s Regiment (Liverpool) – from 1958, the King’s Regiment – was born in the British military hospital (BMH) in Berlin, (West) Germany, in 1950. The Taylors later travelled back to the UK, and while Robert’s father then went to Malaya (now Malaysia), his family stayed at Maghull Transit Camp near Liverpool. The family’s next accompanied posting was to Nairobi, Kenya, from late 1959 to mid-1961, where Robert attended the army school near Wilson Airfield. Robert particularly recalls the journeys between home and school:

‘We were collected either by army buses or the old Bedford 3-ton trucks, and were taken either to or from the collection or drop-off points in the suburbs where we lived. We were one of only a couple of families who lived in what was then Nairobi South C, at the time a very Indian suburb. Once, a friend and I decided to walk home through Wilson Airport and across the open bush of Nairobi National Park, a game park, totally unaware of the danger posed by the wild animals (and possible remnants of the Mau Mau rebels). (We “suffered” in other ways for our miscreant behaviour.) The transport ride was usually about an hour long, having as it did to go to the various suburbs, and it was because of this long, tedious journey that we decided to walk.’

Robert Taylor (b.1950).

A GUIDE FOR FAMILIES IN GERMANY, MAY 1954: TRAVEL

‘Part 6 – Leave and Travel

2. QUESTIONS and ANSWERS

Q6: May schoolchildren visit their parents in Germany free of charge?

A: There are two sets of conditions under which children may visit their parents free of charge:

(a) Children are eligible for one free visit (between the age of 6 years and 17 years inclusive) during the father’s tour in GERMANY, provided:

(i) The father has a further six months to serve overseas from the date of the child’s departure from UK.

(ii) A deferred passage was claimed by the husband on his original OP UNION application.

(b) They are also eligible for a free visit once during a three year period of service outside the UK. If a period of service is longer than three years parents will be entitled to visits by children every two years.

NB – The child must not have had a normal OP UNION family passage during the same tour for at least two years.

Full details are contained in BAOR Standing Orders, Part XXII.

Q7: May schoolchildren visit their parents in Germany on repayment?

A: Yes. Providing the child is between the age of 6 years and 18 years inclusive he/she may visit Germany with the organised parties during school holidays on repayment. These are organised by Messrs Thomas Cook. Units have instructions for making applications and details of costs. You may also make private arrangements for travel by civil ship or by air.

Part 8 – Road Transport and Private Cars

1. GENERAL

Owing to the lack of public road transport services in Germany, families may use WD transport subject to certain conditions and limitations. Full details of the current rules have been issued to all units and can therefore be obtained from your unit orderly room.

Private cars may be imported into Germany under individual arrangements. New cars may be purchased from UK free of purchase tax from the export quota and full details of this scheme can be obtained from any car agents in the UK or Germany.

Q8: Are my children allowed the same number of journeys as myself?

A: Chargeable children, yes. Children under three years of age are disregarded for this purpose.

Q9: Are children allowed additional recreational journeys for Scout and Guide activities?

A: No. Journeys undertaken in connection with Boy Scout or Girl Guide activities count against the normal entitlement and are subject to the distance regulations.

Q13: May I use WD transport for conveyance to Church or Sunday School?

A: Yes. Transport may be provided for one free journey per head per week to the nearest church service of the denomination of the individual concerned. In addition, a further free journey is authorised for children between the ages of 3–15 for attendance at the nearest Sunday School of the child’s denomination. If accompanied by an adult, the journey must be paid for by the adult at recreational rates and will count against his/her entitlement.’

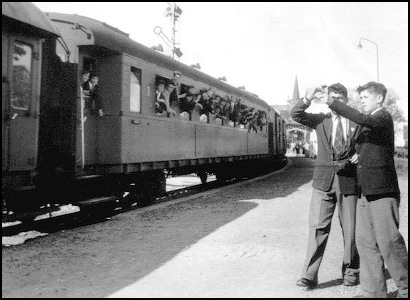

PICTURES: KING ALFRED SCHOOL (KAS) TRAINS

Thanks to Peter Watson for providing TACA with these three images of trains that transported the pupils of King Alfred School (KAS) to and from Plön (or Ploen) at the beginning and end of each term. As Peter comments, 'the fictitious St Trinian's/Hogwarts' expresses were a mere shadow compared to the realities of the BAOR school trains'. For more information on this boarding school in Germany, and for further details of the trains that served it, see TACA's 'SCHOOLING' page, and particularly Peter's piece, 'BACKGROUND INFORMATION: BAOR SECONDARY SCHOOLS AND SPECIAL TRAINS'.

Above and below: The KAS school train departs from Plön at the start of the Easter 1956 school holidays. (Photo courtesy of the KAS Wyvern Club/Mr John Lowe.)

Below: The KAS school train leaves Plön at the end of the 1955 summer term. (Photo courtesy of the KAS Wyvern Club/HQ BAOR Public Relations.)

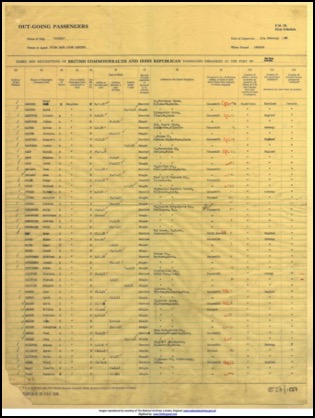

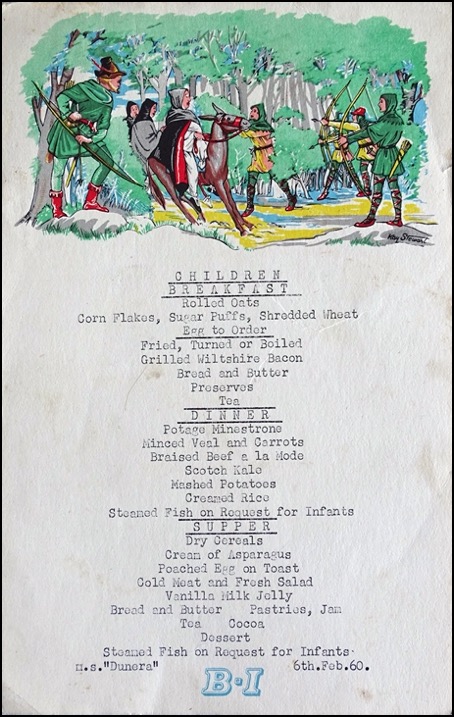

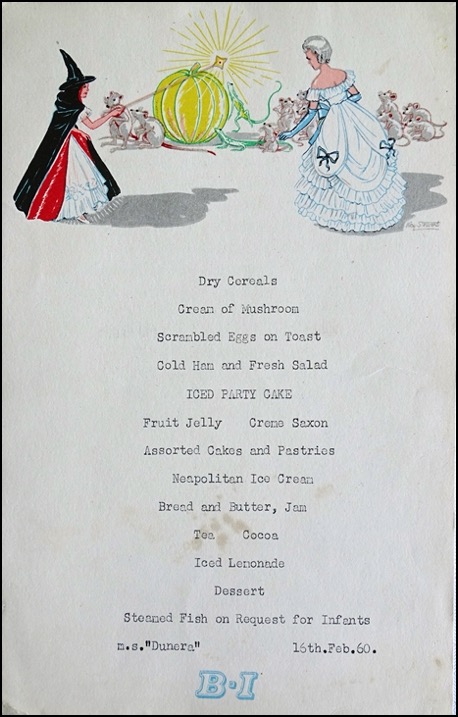

PICTURES: MEMENTOES OF A JOURNEY TO JAMAICA ABOARD THE MS DUNERA, 1960

In a previous contribution, Barbara Rayner (née Messenger) shared photographs of her primary-school class in Sennelager, (West) Germany, as well as of the MS Dunera, on which she and her family travelled to Jamaica in 1960 (‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘A COUPLE OF YEARS AFTER THE CLASS PHOTO WAS TAKEN, WE WERE ON A SIX-WEEK VOYAGE TO JAMAICA’’). Barbara has now generously contributed more images and memories of her army childhood, including the passenger list for the six-week voyage on MS Dunera and two charmingly illustrated children’s menus from the same journey.

Below: This MS Dunera children’s menu, illustrated with a scene from the legend of Robin Hood, is dated 6 February 1960. Breakfast options include cereal and Wiltshire bacon; minced veal and carrots and braised beef à la mode are among the dinner choices; while poached egg on toast and vanilla milk jelly are among the dishes offered for supper.

Above: Her fairy godmother is depicted transforming a pumpkin into a coach for Cinderella at the top of MS Dunera’s children’s menu for 16 February 1960. Included among the food on offer are cold ham and fresh salad, iced party cake and bread and butter with jam.

For more of Barbara’s memories and mementoes, click on the links: ‘PICTURES: TROOPSHIP TIPS, BOAC TICKETS AND TRAVELLING TO AND FROM TRIPOLI, LIBYA, 1950S (see above)’; ‘PICTURES: ‘A GUIDE TO FAMILIES GOING TO THE CARIBBEAN’, 1959, AND REVISITING JAMAICA’S UP PARK CAMP IN 1990’; ‘PICTURES: ‘OUR HOUSE IN JAMAICA, PICTURED IN 1960 AND IN 1990’; and ‘PICTURE: A SCHOOL PHOTOGRAPH, UP PARK CAMP, JAMAICA, EARLY 1960S’.

PERSONAL STORY: FROM BRITAIN TO GERMANY, VIA KENYA

This army child's story begins when she was around two years old:

'Father joined the army [the Royal Artillery] after his war service and was posted to Korea in early 1952. At that time, we all lived in Portsmouth, mother's home town, and my brother was born there in 1952. From Korea, without coming home, my father was posted to Hong Kong and Malaya and returned home in 1955. We left Portsmouth to be posted to Mile End Camp, Oswestry, where my youngest sister was born. From there, we all went to Kimnel Camp, Rhyl, and then to private hirings in Market Lavington, near Devizes, while my father's regiment was at Netheravon. In 1961, he joined 3 RHA [Royal Horse Artillery], having heard that they were going to Malaya, but they were posted to Kenya instead.

Upon reaching Mombasa, we travelled by train (overnight and hot) to Gilgil, about 50 miles from Nairobi. Because I was of secondary age, I had to board, either in Kenya or the UK. My first school, Nakuru Girls High, wasn't bad once I got used to it, but closed down and we then had to go to The Highlands, Eldoret, where I did not have a happy time. The highlight of terms there was the sight of the army bus coming to take us back to Gilgil.

We spent three years in Kenya, coming back after independence, and after a short time in the UK, where I took my exams, we were posted to Detmold, in Germany. I took a job as a nanny, having few qualifications (i.e., no German and no typing skills), but was able to go with my surrogate family to the USA. During that time, my father left the army.'

Margaret Cleeve (b.1948).

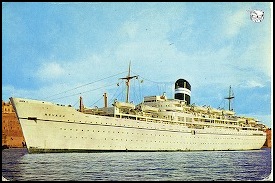

PICTURE: THE MV FREE ENTERPRISE VIII

Many army children crossed the Strait of Dover with their families on the MV Free Enterprise VIII between 1974 and 1987, generally en route to (West) German or British postings, or to boarding school. Owned by Townsend Thoreson, this passenger ferry carried road vehicles, as well as foot passengers, between the ports of Dover, Kent, and Zeebrugge, Belgium. The MV Free Enterprise VIII is pictured outside Dover below, in a postcard dating from the 1970s.

LINKS

The following links relating to the transportation of army children may be of interest.

- To browse through an informative picture gallery of troopships, visit: http://www.britisharmedforces.org/pages/nat_troopships.htm.

- For Peter Watson's outline of the routes taken by the special trains that took pupils to and from Prince Rupert School (PRS), Wilhelmshaven, and King Albert School (KAS), Plön, as well as for the travel arrangements made for those who attended the Windsor schools in Hamm (all BFES secondary boarding schools in West Germany) during the Cold War era, go to TACA's 'SCHOOLING' page.

TACA TRAVEL ALBUM: BY SEA